The recent exhibition catalog wo/man ray: The Seductions of Photography from the Centro Italiano per la Fotografia in Turin, presents a new study on Man Ray’s photography and the role of women as a central figure throughout his art and life. In the opening essay, curator Walter Guadagnini identifies the ambiguous duality of Man Ray’s nature as being the same type of duality found in photography itself; a union of poetry and the document. “Man Ray’s history indissolubly interweaves with a large number of women,” writes Guadagnini, “Woman who almost always have an equally fascinating story of their own to tell–again from a biographical and artistic standpoint.”

The recent exhibition catalog wo/man ray: The Seductions of Photography from the Centro Italiano per la Fotografia in Turin, presents a new study on Man Ray’s photography and the role of women as a central figure throughout his art and life. In the opening essay, curator Walter Guadagnini identifies the ambiguous duality of Man Ray’s nature as being the same type of duality found in photography itself; a union of poetry and the document. “Man Ray’s history indissolubly interweaves with a large number of women,” writes Guadagnini, “Woman who almost always have an equally fascinating story of their own to tell–again from a biographical and artistic standpoint.”

The dichotomy of the “female figure” in the art of Man Ray (1890-1976) is a poetic study of desire, fantasy and sexuality amid known historical documentation, while some figures still remain excluded or too “fringe” to bother with. Wo/man ray, is filled with over 200 portraits, nudes and abstractions, many unpublished before — an inventory mixing the model-muse with extraordinary public figures and woman artists crossing paths with Man Ray in this important era of experimentation and upheaval. Illuminating the female intersections in Man Ray’s circle is an area ripe for investigation and is hinted at in the visual evidence. However the essays of wo/man ray don’t live up to the idea–which was perhaps too grandiose a project to manage.

Man Ray, Adrienne Fidelin in Harper’s Bazaar, 1937

Rarely seen images of Guadeloupean dancer and black model Adriennne Fidelin (1915-2004), are a delight to see printed in wo/man ray. “More than a muse, Fidelin was one of many individuals and entities who—in a newfound confluence of African diasporic cultures in the interwar period—changed the face of modernism,” wrote historian and Man Ray expert Wendy A. Grossman, in her groundbreaking essay “Unmasking Adrienne Fidelin: Picasso, Man Ray, and the (In)Visibility of Racial Difference,” where lost narratives are uncovered — including Fidelin’s attribution as the model for a long forgotten painting by Picasso — a portrait inspired by Man Ray’s photo. Fidelin’s name and history disappeared after the war. “Her relationship with Man Ray failed to survive the separation precipitated by the occupation of Paris by German troops on June 14, 1940, and the artist’s subsequent flight back to the United States to escape the war,” notes Grossman, who is also author of Man Ray: Human Equations and is currently working on a book about Fidelin.

The subject of nearly 400 Man Ray photographs, Fidelin was also the first Black women to be featured in an American fashion magazine, (Harper’s Bazaar) modeling exotic garb and a Belgian Congo hat, at a time when William Randolph Hearst’s racist policy forbid Black women to be a featured magazine subject. Fidelin was also featured in Black Models: From Géricault to Matisse, a 2019 exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, introduced to the curator by Grossman. The exhibition catalog Posing Modernity written by Denise Murrell, brought this new context into viewing works of art. “The more you know about the socio-historical context, the more you are able to imagine a variety of interpretations and conclusions,” said Murrell.

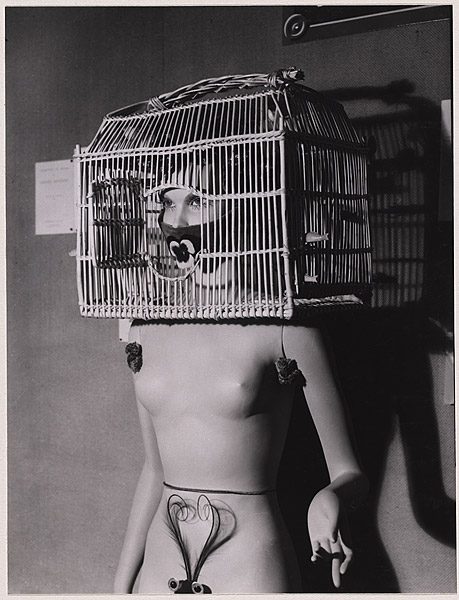

Man Ray, Mannequin de André Masson, 1938

A strange feature in wo/man ray is an entire chapter devoted to the rare Man Ray portfolios; Les mannequins and Réssurection des mannequins –based on the infamous 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme organized by André Breton and Paul Éluard, where surrealist artists and writers designed female mannequins into a maze of fetishized and objectified fantasy sculptures, much like the female doll creations of the German artist Hans Bellmer. The entire sixteen image portfolio of Réssurection des mannequins is reproduced in wo/man ray along with detailed descriptions of their surreal alienation imagery at the expense of the female anatomy. Although these bizarre women intersecting with Man Ray were not of flesh and blood, they were characterized in Mauro Carrera’s essay as the “pinnacle” achievement of the Surrealist movement and “reminiscent of horror b-movies.”

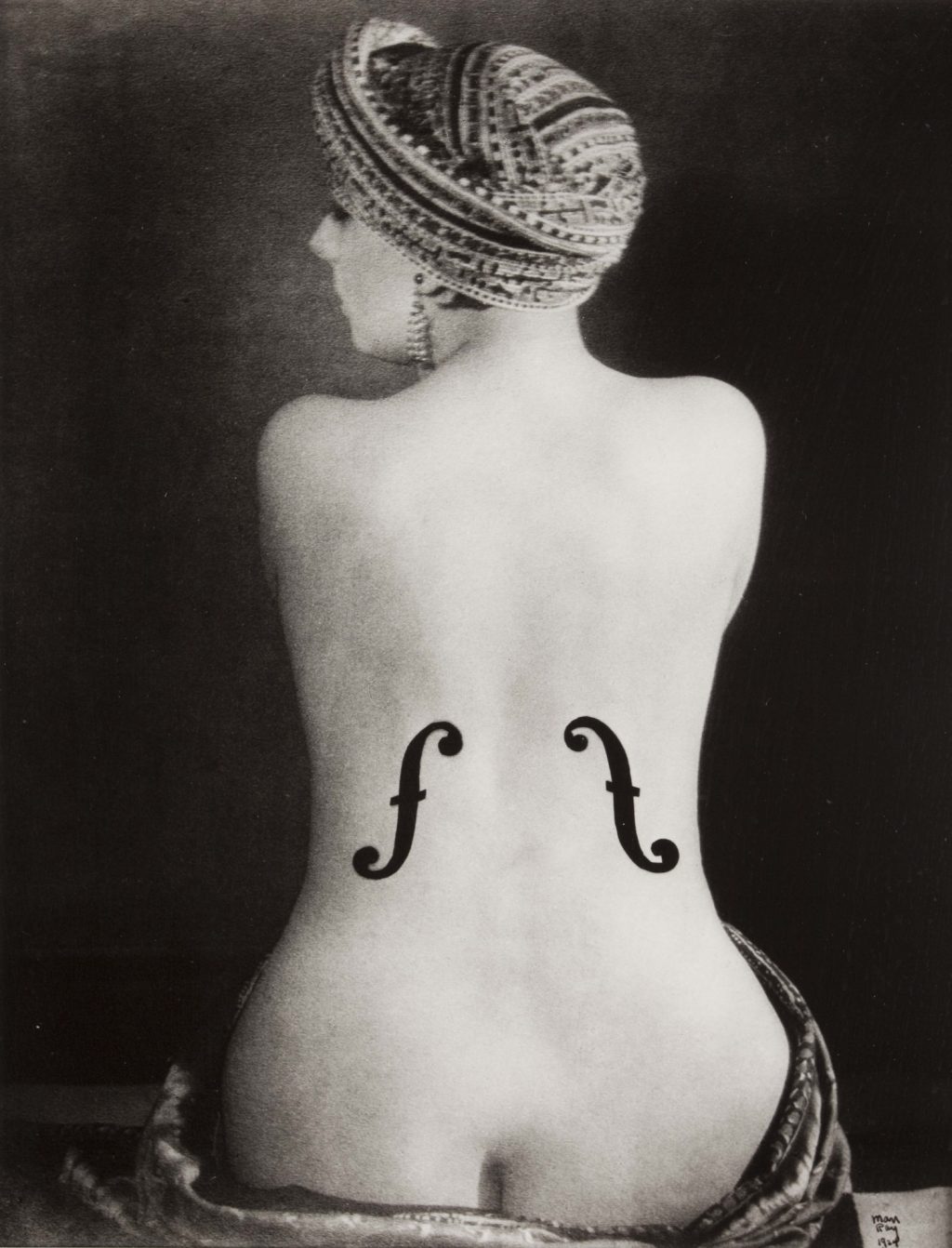

Many Ray, La Violin d’Ingres (1924)

Alice Ernestine Prin (1901-1953) better known as Kiki d’Montparnasse, rose out of poverty to become a painter, model, literary muse, actress, cabaret singer, and one of Man Ray’s earliest models and lovers. Kiki was the subject of two of Man Ray’s most famous photographic works; La Violin d’Ingres (1924) and Noie et blanche (1926), images printed in fashion magazines, giving Man Ray a wealth of portrait work, helping establish his career as a photographer of fashion and celebrity.

Kiki published her memoir The Education of a French Model in 1930 to great acclaim, which was banned in America until the 1970s, due to her open sexuality and “immoral” lifestyle as the reigning Queen of Bohemia. In his forward to The Education of a French Model, Ernest Hemingway wrote,”It was also very pleasant after working, to see Kiki. She was very wonderful to look at. Having a fine face to start with she had made it a work of art. She had a wonderfully beautiful body and a fine voice, talking voice, not singing voice, and she certainly dominated the era of Montparnasse more than Queen Victoria ever dominated the Victorian Era.” Kiki was also the recent subject of an award winning graphic novel.

In Man Ray’s solipsistic autobiography Self Portrait (a ten year undertaking), he recalls how often Kiki expressed her love for him and the times she was jealous of others during their six years together. “I did take Kiki sometimes to the cafés of my more intellectual friends, or to their homes,” wrote Man Ray, “She was perfectly at ease and amused everyone with her quips, but got bored if the conversation became too abstract for her.” Despite its imperfections and defensiveness Self Portrait is still an important and useful document in clarifying Man Ray’s motivations and began a slide of new research that has preserved his legacy.

Photographer and model Dora Maar (1907-1997) is currently the subject of recent exhibitions at the Tate and Pomoidou Centre. The catalog Dora Maar presents 240 images of her work, long neglected in photo histories. Finding Dora Maar is a brilliant investigative biography and reconstruction of her life in novel form by Bridgette Benkemoun – a French bestseller recently translated into English. Constructed like a detective novel through the apartments, galleries and streets of Paris using Maar’s personal address book (found on an ebay auction) – following her activities and interactions with friends, many who were great artistic luminaries of the twenties and thirties. Her inclusion in the photo chapter “Lee, Dora & Meret” appears like a butterfly collection of beautiful specimens in wo/man ray, who are “developing strategies for the portrayal of the body undoubtedly reminiscent of Man Ray’s” to quote Guadagnini on Lee Miller.

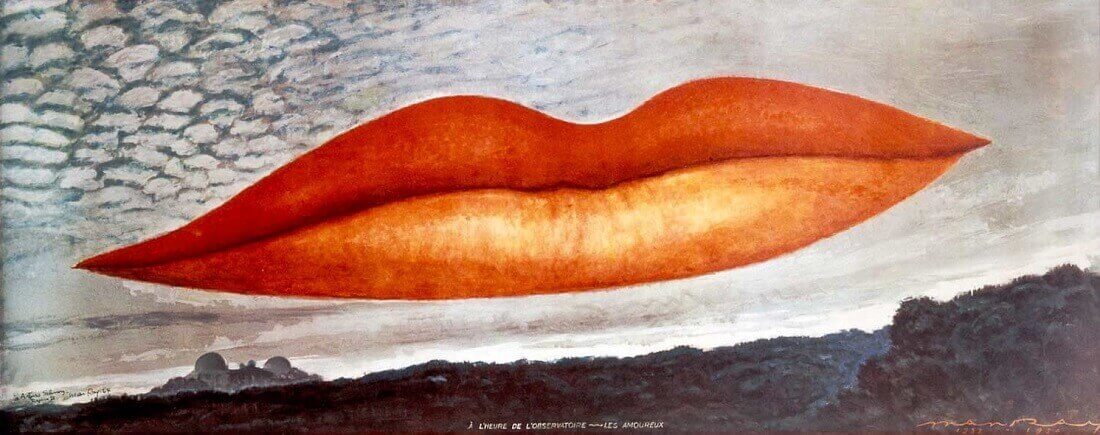

Lee Miller (1907-1977) played a central role in Man Ray’s photography as assistant, co-creator, model, muse and love interest who also drove him to the brink of despair. Miller inspired Man Ray’s most iconic painting, “Observatory Time — The Lovers,” where her monstrous lips float across the sky as a dream-like spectre. Miller, the subject of a biography by Carolyn Burke, and another by her son Anthony Penrose, remained a mysterious force throughout her life, reinventing herself and keeping silent about it. A collection of her fine art photography was recently released as Surrealist Lee Miller, and her surprising later life as gourmet chef was revealed in the new book: Lee Miller: A Life with Food, Friends & Recipes.

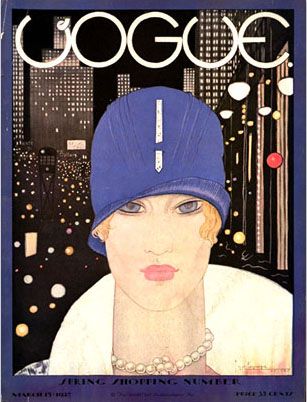

George Lepape, cover illustration of Lee Miller, Vogue magazine, 1927

Miller was one of only four female photographers who covered World War II for the Armed forces of the United States — and the first photojournalist to document the Nazi horrors at the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp in Germany. After the trauma of Dachau, Miller and her close friend and fellow photojournalist David E Scherman, went to Munich and paid a visit to Adolf Hitler’s private apartment where they each took turns bathing in Hitler’s bathtub –their first bath in over three weeks of war reportage.

Penrose learned about his mother’s history soon after her death while rummaging through photographs and ephemera found in her attic –a history which included her rape at the age of seven, nude photos taken by her father as a teenager, and a successful modeling career in which she was featured on the cover of Vogue at the age of nineteen. The novel Age of Light is decent bio-fiction of Lee Miller’s life — a first novel by Whitney Scharer, it deletes large sections of her life but does well when focused on her relationship to Man Ray and the spirit of their life and times in Paris.

***

President of the Centro Italiano per la Fotografia Emanuele Chieli, proclaimed his Man Ray exhibition; “Symbolizes a new approach to an ever-relevant theme – that of the role of women in every sphere of society, obviously including art… there has never been such a marked comparison between the maestro and some of these figures on the artistic level… above all the independent value of the research of these female photographers, leading figures on the worldwide cultural scene.” The catalog includes several Bernice Abbott portraits (a Man Ray assistant) who shared in the discovery of Atget, Dora Maar’s street, fashion and abstractions, and Lee Miller’s surrealist work. The catalog leaves open many questions about how these and many other relationships crossed with Man Ray and the larger history of photography. The omission of stories and histories by the many models and female relationships hinted at in wo/man ray — is a missed opportunity to live up to its ideal. By exploring these significant “leading figures of the cultural scene,” it helps widen the discussion and scope of women’s contribution to the art of modernism, their influence on maestro Man Ray and beyond. When photography opens its conversation wider, everyone benefits.

Note: Books mentioned in this essay are available at Book Beat direct or at or Bookhop.com page– thank you for your support. For questions or inquiries call (248) 968-1190