The Lost Writings

The Lost Writings

by Franz Kafka (Michael Hofmann, trans.

New Directions

“Respected guests! It may have come to your attention that I hold a world record, but if you were to ask me how I came by it, I would have no satisfactory reply. You see, I really can’t swim at all. I always wanted to learn, but I never had occasion to. So how come I was sent by my country to participate in the Olympic Games? A question that preoccupies me too. To begin with, I must tell you that this is not my fatherland, and try as I may, I cannot understand a word of what is spoken here. The most obvious explanation would be some mix-up, but there is no mix-up, I hold the record, I went home, my name is what it is said to be, everything so far is true, but beyond that point nothing is true, I am not in my homeland, I do not know you and cannot understand you. Now something else that not exactly—but at least diffusely—repudiates the idea of a mix-up: it doesn’t greatly bother me that I don’t understand you, nor does it seem to greatly bother you that you don’t understand me. . . But to get back to my world record. . .”

Notice the use of an “o” rather than “a” in the title’s adjective. The presumptive last unpublished writings of Kafka are among a previously unexamined trove of papers by Kafka from the Max Brod estate that the Israeli government confiscated a couple of years ago in an international dispute over rights to Kafka’s material legacy. So, we have the lost to tide us over until the last arrive.

And what we have is what we long for from Kafka: new parables and gnomic ironies rendered in tones simultaneously realist, fatalist, and Talmudic. Almost all are fragments, scraps running from one paragraph to four pages. But in Kafka, setting and tone are inseparable from fate, which Kafka has a knack for establishing in one or two sentences. “Kafkaesque irony” often means that, though the possibilities before us are endless, our fate is singular and unavoidable.

Michael Hofmann’s translation is a seamlessly idiomatic American English, though devoid of contemporary anachronisms.

Orange

Orange

Essay and photos by Orhan Pamuk

(Ekin Oklap, translator)

Steidl Verlag

Orhan Pamuk, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006, documents in photographs neighborhoods in Istanbul by inexpensive sodium bulbs. These bulbs imbue their surroundings with an orange aura—a warm color ideal for memories and happy associations. But a poor color, as it turns out, for driver visibility.

“Driver visibility” hardly seems to be the issue, though, in these neighborhoods, where most people walk, and they walk on the narrow lanes and alleys photographed here, cobbled, bricked, and asphalted. Sidewalks, such as they are, often serve as extra room to set up tables and chairs in front of cafés, party stores, and apartment buildings.

image © Orhan Pamuk

I’ve been in neighborhoods like these, though in Shanghai—places where friends meet to talk, eat, and drink; families go on after-dinner walks; fruit and vendors sell their goods; and children play—neighborhoods (and lighting) also quickly disappearing as gentrification brings in wealthier residents and chain restaurants vending mass-produced lumps of biomass.

But besides the warm feelings evoked by the lighting, Pamuk also tells us what and who we are looking at, the significance of who these residents are and their specific social standing: The number of flags hung in street rising with the tide of ugly nationalism; “the rapid rise in the number of Syrian immigrants and of people wearing religious clothing out on the streets of Istanbul” (the latter behavior used to be illegal). The what and who are qualities I remain ignorant of in my own photos.

image © Orhan Pamuk

The Daughters of Ys

The Daughters of Ys

Story by M. T. Anderson

Illustrations by Jo Rioux

First Second

T. Anderson’s morally nuanced new book (well-illustrated throughout by Jo Rioux) re-casts an old Celtic legend about two daughters of a powerful witch and her (all-too) human husband. The mother dies when the girls are young, leaving their father a widower, alone to rule the island of Ys—an island created as a favor to the mother, whose subsequent safety after the mother’s death requires payment to the sea god.

As the daughters age, the oldest daughter, Rozenn, favors the outdoors and exploration, showing little interest in court life. The younger daughter, Dahut, has more cosmopolitan interests than her sisters, and comes to love the court life while the execution of government duties falls more and more on her hands, including paying the debt to the sea god. Dahut comes to resent her older sister, whom she sees as one in line for all the power that comes with being the eldest while refusing to take on the responsibilities that come with one’s station.

One night, while roaming through the woods, Rozenn stumbles upon Corentin*, a holy man whose fate is to catch and eat the same fish every day. He eats half of the fish, tosses the other half back in the water, and waits for the fish to regrow the next day. It is also his only companion, and every day he must butcher it to survive. Corentin does not know if his fate is a blessing or curse.

Unbeknownst to Rozenn, Dahut also performs a version of Corentin’s fate each night: to catch a different man at court, have sex with and kill him, then toss his corpse into the ocean. That is her debt to the sea god in exchange for keeping Ys safe and making available to Ys the riches from plentiful shipwrecks.

One night, Rozenn’s boyfriend Briac sleeps with Dahut but immediately confesses his remorse for betraying Rozenn. In return, leaving him utterly ignorant of how close he came to being killed, Dahut spares his life. They are caught as Rozenn approaches Dahut’s room while Briac exits. After the sisters tussle, Dahut says, “Always remember that I was kind.” The rest of the book deals with the consequences of that kindness for Ys.

*Corentin eventually became both the patron saint of seafood (!) and “one of the seven founding saints of Brittany” (per Wikipedia).

The Angriest Dog in the World

by David Lynch

Rotland Press

I love this book, it made me laugh. But the “humor” requires having a love of the absurd, which most folks seem to have little tolerance for. A sense of the absurd as well as a love of constraints: The book consists only of three panels that are repeated in every strip throughout the book, and each strip is five panels long.

The first panel is a block of text introducing the dog. The next four panels show the same image repeated three times: a dog in a back yard, tied to a stake in the ground with a chain, against which it tightly tugs while growling. The fourth panel is the same as the rest, only at night. Apart from that, the only variable, which comes from the back window of the house, is the use of speech balloons.

My favorite strips are those in which only one panel has a speech balloon. That spare, static setting balances what is said with when it is said. Not just the timing between a setup and the punchline, but also the time after one joke and a new silence that becomes a tension in anticipation of a punchline that presumably explains the gap of silence leading up to the joke. Ryan Standfest’s editing of the book helps shape the book’s pacing, which resembles Steven Wright’s. The pictures and humor also put me in mind of John Lurie’s paintings, which made me wonder if I could cue Lurie’s music to Lynch’s films, but that’s a different train of thought. [Ed. Note: Rotland Press books can only be ordered from them directly at this time.]

American Fascism Now

American Fascism Now

By Sue Coe and Stephen F. Eisenman

Rotland Press

Sue Coe has used her linocutting skills in service to human and animal rights issues for decades now. I first became aware of her work via Raw, in particular her Raw One-Shots How to Commit Suicide in South Africa (on Stephen Biko) and X (on Malcolm X). Then some years later, I saw her works in a university museum, this time focusing on the pork industry, depicting the brutality required to sustain it, from birth to death of the pigs. Painted on butcher paper in greys, rusts, blacks, and reds, the medium and the color choices were the rhetorical choices that reinforced the semantic content of the pictorial images.

In American Fascism Now, Coe uses her linocutting skills to depict the moral depravity of the Trump years. Coe has always been a propagandist for moral truth, and linocuts allows her to blend the starkness of political contrasts with the linocut’s black/white, and the gouging of linocuts equates with the moral violence of the figures she depicts.

Stephen F. Eisenman frames Coe’s images with a succinct historical contextualization of American fascism compared to its European predecessors’, and lists the warning signs historians agree represent and define fascism in general.

An excellent record of the times. [Ed. Note: Rotland Press books can only be ordered from them directly at this time.]

Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart

Ferdinand, the Man with the Kind Heart

by Irmgard Keun

(Michael Hofmann, translator)

Other Press

The foundation of the novel is simple: (1) several dozen character studies are written that describe the peccadillos of some mild eccentric, and include an anecdote or two to illustrate the claims; and (2) Ferdinand is given a (flimsy) motivation to meet these people. His motivations? (a) Ditch his fiancée. (A problem for the “kind-hearted.”) Surely, somewhere among his aquaintances is one willing to woo away Luise. Why? (b) To be alone. After serving in the German army and living as a POW, Ferdinand would like to be left alone.

His encounters with various types of shopkeepers, artists, businessmen, and other middle-class people illustrate the ongoing hypocrisies of a nascent post-WWII Germany—including a party hosted in honor of one neighbor’s successful (i.e., government-sanctioned) de-Nazification, so that he could no longer be held responsible, as a mid-level Nazi apparatchik, for any crimes against humanity. Instead, he is official re-labeled as a “fellow traveler,” which allows him to take no responsibility for fulfilling his Nazi duties.

Here’s Ferdinand mulling over his life in the Nazi regime:

- “When I was a soldier, I could never be alone, when I was a prisoner of war I was never alone, and as a wretched returnee, still less so. Nothing against the Widow Stabhorn, who lets me live in her passage, and nothing against her thousand grandchildren either. They are splendid optimistic people full of the will to succeed, and I am lucky to be in their midst. Only when I am with them, I am not alone I am living in a sort of family association, and I would like just for once, and not necessarily for long, not to be living in any association. No family association, no provisional association, no national association, no professional association—not in any kind of association at all.”

The novel is often funny, and the “kindnesses” Ferdinand offers women is something Dorothy Parker would have enjoyed. A woman writer (Irmgard Keun) presenting a male character (Ferdinand) who provides lists of things “women like to hear”—the sneers are for both the men who say them and the women who like having them said.

The humor is as caustic as the subjects. Apart from what a reader might expect a witness to report about fighting in a war, the origin of Ferdinand’s weariness of human horrors remain obscure and implicit. But we also learn that Ferdinand already had these tendencies before the war: “[W]hen I first met Luise, I was still less normal than I am today.” Whatever that “less normal” means, he also tells us that “in POW camp, I came to thoroughly dislike myself. . . And I always, always wanted to be alone.”

How old was Ferdinand when the war broke out—late teens, early twenties? How long had he been sucked in by Nazi propaganda before then? POW camp is when he seems to have had his personal revelation:

- “I no longer saw human beings, all I saw were the mechanical manifestations of a force that hypnotized me to the point of crippling despair. Sometimes I had the feeling that the world was split in two: one half was me and the other was a huge mass of things, animals, humans, whose sole objective was to harry and torture and mock me. I couldn’t understand that others could have such an influence on me. It was hopeless. I was so terrorized I couldn’t even cry any more. Otherwise, believe me, I would have. I was used to so much freedom from when I was a boy, colorful, tender freedom. I knew that poverty had edges, and life and rough edges that you make yourself. But even they can be good. I knew forces for good and ill, but I didn’t know what force was.”

“The most disgusting thing of all was that someone was turning to me for human sympathy when he was part of the machine and represented the machine that was abusing me and violating me.” It’s that kind of comedy.

Tarka the Otter

Tarka the Otter

by Henry Williamson

NYRB Classics

Williamson’s descriptions of natural scenery and animal behaviors include a heavy stock of specific—even regional—names of animals and their body parts, and plants and their parts, and specific verbs given to the behaviors of specific plants, animals, winds, waters, and seasons. If you’re willing to look up pictures of birds, trees, shrubs, and weeds you’ve never heard of or seen before, you’ll quickly realize that a seemingly empty sward of fields, streams, and ponds is a rich, teeming hubbub of death and beauty.

While Tarka is the protagonist, Williamson minimizes the anthropomorphism, keeping it just as much as to the assignation of names as is possible, and minimizing verb choices that indicate motivation to those verbs that refer to hunting and mating. Tarka is Williamson’s attempt to write a short life of a biosystem from the point of view of an otter, using strands of scientifically accurate descriptions to weave an engaging story.

As a side note, when originally released 1927 Tarka was marketed as a Young Adult book. Now it’s with the adult lit. What gives? Well, for one, our general, collective alienation from even the things growing and happening in our own yards means that now every weed and tit-bird has to be googled. What many suburban and rural readers, aged 12-18, already knew 60 or so years ago, were the names of the life forms around them. As that world quickly recedes, research is required to virtually restore it in one’s imagination, pieced together from snapshots found online.

One Picture Book Two

Nazraeli Books

This elegantly produced series of photography books follows in the steps of Nazraeli’s previous series, One Picture Book , 100 small-format photography books, each devoted to the work of a single photographer. Now 20 books into the next series, One Picture Book Two currently consists of four books of five slip-cased and numbered editions of 500, each including a baker’s dozen of photographs and a 5” x 7” print signed by the photographer. The topics, approaches, techniques are wide-ranging, from staged to in situ scenes. Photographers represented include Todd Hido, Laurie Simmons, Daido Moriyama, and Carrie Mae Weems. Available singly or by subscription. [Editor’s note: Book Beat has discontinued stocking these limited editions from Nazraeli press, but many can still be special ordered from us.]

Subjectively, Objective

Subjectively, Objective comes in two different versions each month, one “Monthly Monograph”—a couple dozen pages by a single photographer, often on a single theme—and two monthly “Mini Monographs”—same idea, half the photos, twice the photographers. Both series are printed as hand-numbered editions of 500. (Available singly or by subscription.) While the range of subjects is wide, the approach taken often reminds me of the Bechers and the Düsseldorf school —a dead-pan method that often breaks visual elements into balanced geometric and color relationships among spaces, lines, circles, squares, and rectangles. No romanticizing the landscape or mourning in the rain—the beauty is already there in the quotidian.

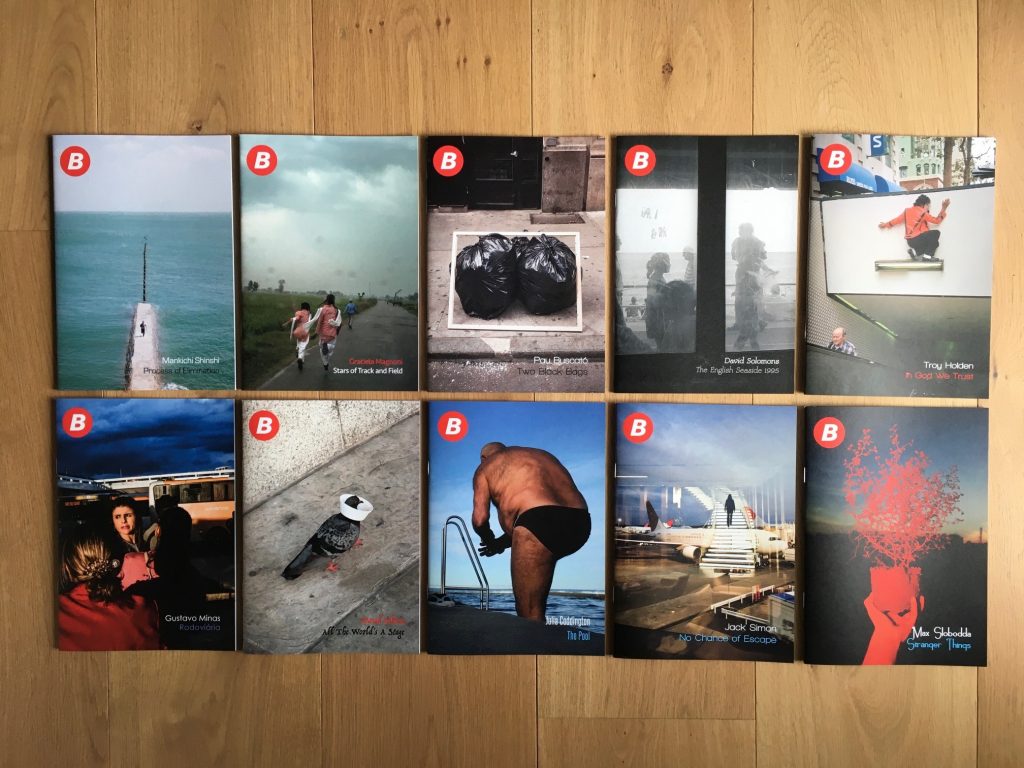

Bump Books david@davidsolomons.com

A quarterly series of street photography printed in England, Bump Books publishes ten 32-page monograph-zines a quarter, in editions of 200-250, available singly or by subscription. Each photographer—rising and established, male and female—presents images on a theme, with nets cast as far as the planet or as close as a nearby town or area. The photos can be witty, as in the works of Martin Parr and Elliott Erwitt, or as simple testimony to the human condition.

Meet Monster: The First Big Monster Book

Meet Monster: The First Big Monster Book

By Ellen Blance and Ann Cook

Illustrations by Quentin Blake

NYRB

In the early 1970s, educators Ellen Blance and Ann Cook interviewed children about a range of topics, then wrote a story for beginning readers, using the children’s own vocabulary. Illustrated by the great Quentin Blake, six interconnected stories focus on the purple, humoid-shaped Monster, beginning with moving to a new town: Monster . . . Comes to the City, Looks for a House, Cleans His House, Looks for a Friend, Meets Lady Monster, and the Magic Umbrella—imitating the way a child’s world grows from self to home to others.

The story is designed as much for children to read to themselves as it is for children to read to adults.

Costumes of the Living

Costumes of the Living

By Gaurav Monga

Snuggly Books

This short book brings together a series of fictional vignettes on the metaphysics of clothing, their force and relationship with their wearers and surroundings. Usually the vignettes are tongue-in-cheek, but there’s a certain “what if” quality to the pieces that imagines fashion as who and what we are in relation to our clothes, and who and what we imagine we become when wearing them. It reminded me of Poe’s “Philosophy of Furniture,” although it’s been 35 years since I last read it. Clothing and its significance could be a topic within Decadent literature, and this small act of Neo-Decadence takes up the, um, mantle and updates it.

Conversations with James Joyce

Conversations with James Joyce

By Arthur Power

Dalkey Archive

I first discovered this little gem in the early ‘80s, when I began my own untutored exploration of James Joyce’s works and the paraphernalia surrounding him, his works, and his life. And I’m happy to see that Dalkey Archive has reprinted it. Power’s book was easily available in the early ‘80s, and for Joyce-ophile’s his (re)collected conversations with Joyce provided hints and insights into Joyce’s work, while also giving us a sense of who’s he when he’s at home.

Decades of academic research has gone under the bridge since this book was first published in 1974, (dis)confirming the value of various crumbs brushed Power’s way by Joyce. So the value in this book today is its ability to convey some measure of the artist and human Joyce was, and this considered opinions on a wide range of topics, including his views on contemporary and past writers—the only place, too, you’ll be able to find those views, unless somebody sees fit to reprint Joyce’s Critical Writings.

The End of Lucie Pellegrin

By Paul Alexis (Richard Robinson, trans.)

Snuggly Books

First published in 1875, The End of Lucie Pellegrin is a short story about a group of four prostitutes who decided to check in on one of their own, Lucie Pellegrin, who had been fabled among the women for having briefly done well for herself, but now was in decline and hadn’t been seen in sometime. They find Lucie alive in her apartment, having assumed she might well be already dead. Their unspoken reason for the assumption? Lucie clearly has tuberculosis, is frail, in debt, and her apartment is wide open for any debt collector to take whatever he sees fit. Together, the five women have a drinking party, at Lucie’s insistence, paid for with the pawn money from her last diamond. It’s a brief slice-of-life narrative, with joy and grief and a lot of foolishness in between. Alexis was apparently an acolyte of Zola’s, and this brief sample of his brand of Naturalism makes me interested in reading more by this author, who apparently otherwise remains untranslated into English.

Landscapes of a Mind Evolving

by Carl Chairenza

LensWork Monograph Series

First published in 1988, Landscapes collects over 60 black and white photographic abstractions and collages. The material basis for the photos were the scraps of paper and other debris collected in the photographer’s studio. Assembled then photographed, the images show mixes of textures, shade, and light with enough harmony to prod the brain into making associations or some sort of “poetic sense” of how these scraps together create a mood.

Difficult Light

Difficult Light

By Tomas González (Andrea Rosenberg, trans.)

Archipelago Books

David is a 78-year-old artist. Due to a rare form of macular degeneration, his vision has for the past couple of years been too compromised to paint, and as he begins the story, he has traded his paint brush for a pen to record the story we read. His eyesight is so bad, however, that he must use a magnifying glass to read it.

His story is a summing up, of balancing joys against sorrows—the most significant sorrows being, not his loss of sight, but the loss of his wife two years ago, and before that—the real motivation for the story—the death of his first-born son nearly twenty years ago, a young man who, due to a car accident, was left paralyzed. And then the paralysis turned into a chronic and intense pain that left him sleepless and depleted the family’s financial resources for his medical treatments.

González’s novel is a beautiful act of love and affirmation of life, seamlessly translated by Andrea Rosenberg.

To me, these reviews are the product of a close and sophisticated reader. One can feel the joy of reading that the reviewer surely is feeling. Its tangibility is interwoven throughout. But what what brings me joy in perusing these reviews is the sheer breadth of material reviewed. My own reading is severely one-dimensional in comparison. Consider me inspired.