Elizabeth at Honoré de Balzac’s Grave, Père Lachaise, Paris

“These shores of the unknown, sands shivering with anguish or anticipation, are fringed with the very substance of our minds.”

–Louis Aragon, Paris Peasant

The cemeteries of Paris are silent parks of small temples, masoleums, bronzes, altars, marble statuary, and stone seraphim. They are the permanent homes of artistic and literary notables. Time moves slow in these parks connected to the seasons, the coverture of nature and the past. Across many headstones are chaotic homemade folk tributes, mementos of coins, letters, metro tickets, flowers, plastic toys and pages torn from books and diaries.

The winding cobblestone roads of Père Lachaise are a mysterious passageway through literary history. First opened in 1804, today the cemetery boasts around three and half million visitors annually, making it the most popular necropolis in the world.

Here lies the 12th century remains of history’s most romantic, passionate, and tragic love affair. Héloïse d’Argenteuil was the student of Pierre Abélard, and they were lovers, seperated by public scandal, their bodies finally reunited during a chapel ceremony at Père Lachaise in 1817. This sad inspiring story of overpowering love and grief was saved with their collected letters, and in the poetry of Alexander Pope (1717) and Christina Rossetti (1858).

I see now the vanity of that happiness we had set our hearts upon, as if it were eternal. What fears, what distress have we not suffered for it!

-From a letter by Héloïse to Abélard

Oscar Wilde’s tomb smothered in kisses, 2009

Père Lachaise the permanent home of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), whose body rests under an Assyrian cubist tomb in the form of a winged angel designed by American-Jewish sculptor Jacob Epstein — a design inspired by Wilde’s poem The Sphinx. It is the most visited site in the cemetery. Epstein wrote about creating the tomb:

It was an exceedingly difficult task from the point of view of pleasing people (not that I try to please anyone but myself), for Wilde’s enthusiastic admirers would have liked a Greek youth standing by a broken column, or some scene from his works such as the Young King, which was suggested many times, while to his detractors he was wholly repellent, deserving of no monument. Once again, the stage was set for a discussion that was centred altogether outside the sphere of sculpture. In addition to these things, cemetery sculpture rarely departs from certain very fixed forms, and in Latin countries in particular there is, far more than England, a “cult of the dead”, so that anything original was certain to give offence of some kind.

A plexiglass enclosure was built around the site, a result of the volume of lipstick kisses left by Wilde’s adoring fans. The oil of the lipstick was slowly eroding the rock of the tomb.

An inscription on the tomb wall is from Wilde’s poem “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” it reads:

“And alien tears will fill for him

Pity’s long-broken urn

For his mourners will be outcast men

And outcasts always mourn.”

In 1961 the genitals were smashed off the angel by a vandal. Author Will Self investigated the tomb’s desecration for his essay “Where the Wilde Thing’s Are,” published in The New Statesman, The tomb’s history and Wilde’s death is told in The Scandal of the Tomb of Oscar Wilde. A prosthetic silver penis was created by Rebecca Sheer with artist Leon Johnson in 2000. The reattachment became a filmed performance and artist book titled reMEMBERING Wilde “to symbolically repair the broken phallus on Oscar Wilde’s tomb.”

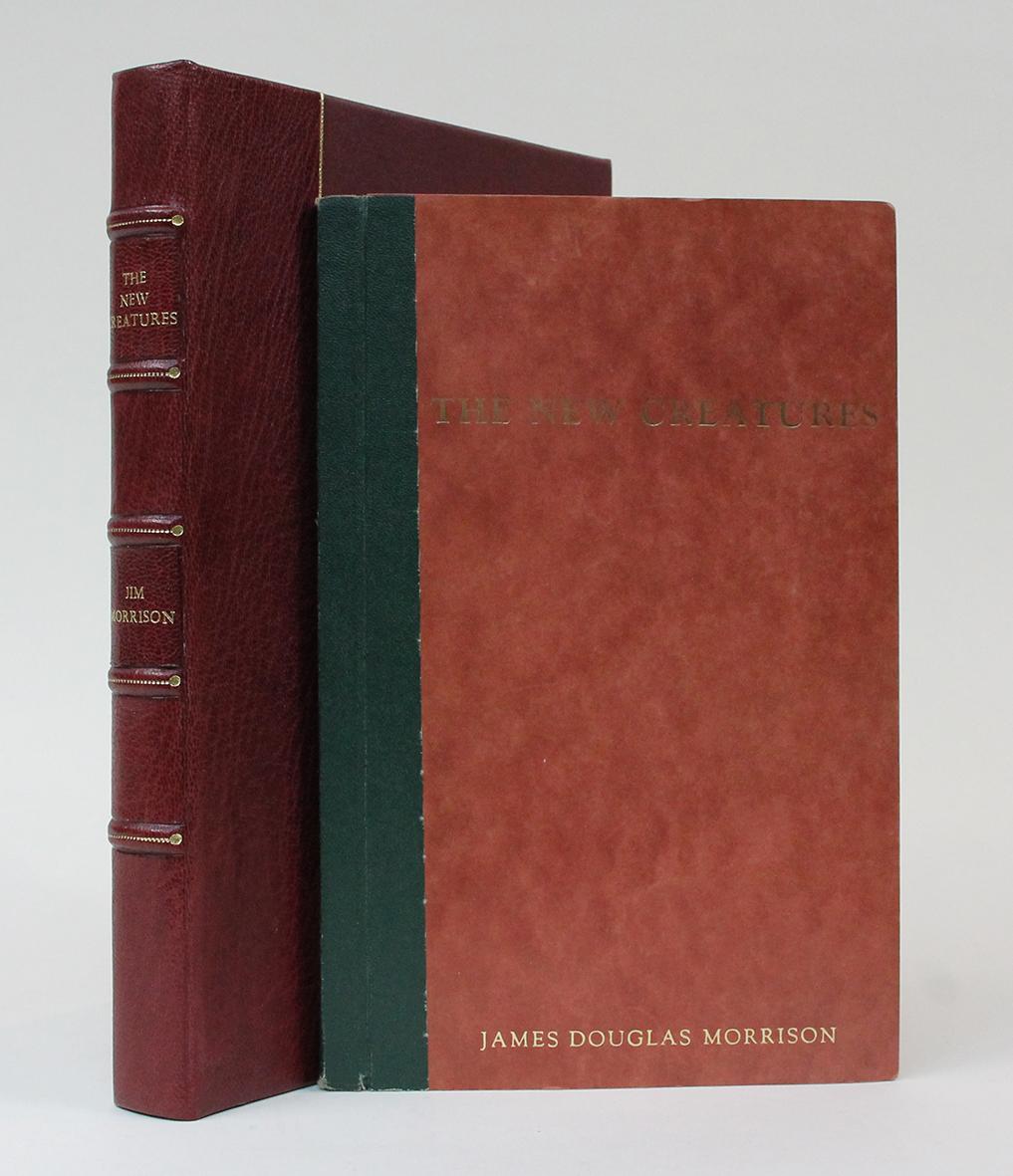

A first edition of The New Creatures, 1969

The gravesite of Jim Morrison, poet-vocalist of the Doors’ is fenced off due to fanatical fans who have stolen his portrait bust, chipped away at the grave’s headstone, and desecrated the site in various ways.

A 2003 video of former Doors members Robbie Kreiger and Ray Manzarek dipict them burning incense and scattering the ashes of a poem over Morrison’s grave.

Morrison’s poetry collection The Lords and The New Creatures, was originally self-published in 1969, as two separate editions of 100 copies. A trade edition published by Simon & Schuster has remained in print since 1970. Two additional poetry and lyric collections: Wilderness (1989) and The American Night (1991) have also remained in print.

The Lords appease us with images. They give us

books, concerts, galleries, shows, cinemas.

Especially the cinemas. Through art they confuse

us and blind us to our enslavement.

Art adorns our prison walls, keeps us silent and diverted and indifferent.

-Jim Morrison, The Lords and New Creatures

In this live version of the Doors apocalyptic epic The End, filmed at the Hollywood Bowl in 1968, Morrison couples the dark Oedipal mood with satiric improvised lyrics.

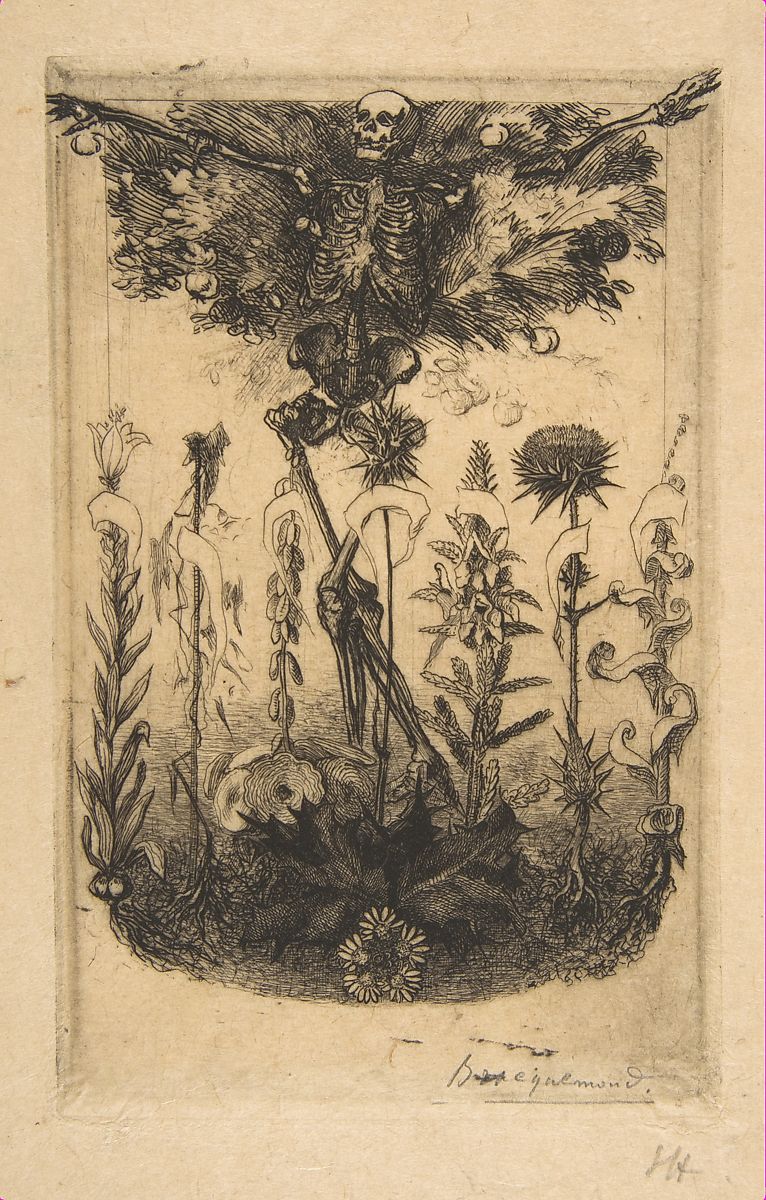

Etching by Félix Bracquemond, Frontispiece for ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’ by Baudelaire (1857): a skeleton standing before seven flowers representing the seven deadly sins.

The cenotaph of poet, translater, and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) is located at the Montparnasse Cemetery, where the landscaping is tightly geometric and flat. Baudelaire was the first author to write on the concept of the flânuer and the city as a site for aesthetic investigation in The Painter and Modern Life.

For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world — impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito. -Charles Baudelaire

Walter Benjamin in his Arcades Project renewed Baudelaire’s investigation of the city by observing the world through fragments, associations and wandering. Benjamin first saw his early vision of the arcades in Louis Aragon’s novelistic tour of the city: Paris Peasant. André Breton described Paris Peasant as, “Intoxicating reveries about a sort of secret life of the city.”

The final poem from Baudelaire’s prose-poem masterwork Flowers of Evil, is The Voyage with its reflections on the passage of time, traveling, and death, it begins:

“For the child, in love with globe, and stamps,

the universe equals his vast appetite.

Ah! How great the world is in the light of the lamps!

In the eyes of memory, how small and slight!”

The Tomb of Charles Baudelaire is a memorial written by poet Stéphan Mallarmé. Mallarmé’s own life came apart with the death of his eight-year-old son Anatole, which inspired his unfinished masterwork: A Tomb for Anatole. In an earlier elegy; The Tomb for Edgar Poe, Mallarmé honors Poe, whose work was (after being translated into French by Baudelaire) foundational to the young Symbolist movement.

“From soil and hostile cloud, what strife!

if our idea fails to sculpt a bas-relief

to ornament the dazzling tomb of Poe”

-Stéphan Mallarmé

On the same block as Baudelaire is Dadaist founder Tristan Tzara’s modest square bronze plaque, barely visible above the weeds.

Nobel laureate Samuel Beckett and his wife Suzanne are located under a nondescript slab of speckled grey granite near the central fountain of the Montparnese cemetery. The New York Times obituary described Beckett’s everyday life in Paris lived not far from the cemetery walls:

Settling down in Paris, Beckett became a familiar figure at Left Bank cafes, continuing his alliance with Joyce while also becoming friends with artists like Marcel Duchamp (with whom he played chess) and Alberto Giacometti. At this time he became involved with Peggy Guggenheim, who nicknamed him Oblomov after the title character in the Ivan Goncharov novel, a man who Miss Guggenheim said was so overcome by apathy that he ”finally did not even have the willpower to get out of bed.”

“Sometimes I went and looked at my grave. The stone was up already. It was a simple Latin cross, white. I wanted to have my name put on it, with the here lies and the date of my birth. Then all it would have wanted was the date of my death. They would not let me. Sometimes I smiled, as if I were dead already.”

-Samuel Beckett, Molloy

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir share a headstone in a shady corner of Montparnese not far from a heavy slab of black granite that marks the sepulcher of Susan Sontag. On meeting Beckett in Berlin, Sontag told biographer Victor Bokris, “Beckett is probably the only person I ever really wanted to meet in the adult part of my life. I was very pleased to be in his presence. I felt and feel a general reverence for him.” It’s not hard to imagine existential conversations between literary neighbors. Máirtín Ó Cadhain did exactly that in his novel The Dirty Dust: Cré Na Cille which The Guardian called, a “splendidly batty 1949 novel.”

A few years after Beckett’s death in 1989, Sontag staged his canonical play Waiting for Godot at the Sarajevo Youth Theatre during the middle of a violent urban war. Sontag found darkly humourous connections in the play’s absurd message of endlessly waiting for the actors and audience of wartime Sarajevo. The play was produced in near darkness by candlelight due the always present danger and lack of electricity. In her essay in the New York Review of Books Sontag asks herself the question of what brought her there;

I was not under the illusion that going to Sarajevo to direct a play would make me useful in the way I could be if I were a doctor or a water systems engineer. It would be a small contribution. But it was the only one of the three things I do—write, make films, and direct in the theater—which yields something that would exist only in Sarajevo, that would be made and consumed there.

In Sarajevo, as anywhere else, there are more than a few people who feel strengthened and consoled by having their sense of reality affirmed and transfigured by art…

Indeed, the question is not why there is any cultural activity in Sarajevo now after seventeen months of siege, but why there isn’t more. Outside a boarded-up movie theater next to the Chamber Theater is a sun-bleached poster for The Silence of the Lambs with a diagonal strip across it that says DANAS (today), which was April 6, 1992, the day movie-going stopped. Since the war began, all of the movie theaters in Sarajevo have stayed shut, even if not all have been severely damaged by shelling. A building in which people gather so predictably would be too tempting a target for the Serb guns; anyway, there is no electricity to run a projector.

Near the hot crowded center of the Montparnese cemetery is the shared grave of surrealist Man Ray and his wife the dancer Juliet Browner. Their headstone reads “Unconcerned But Not Indifferent” and “Together Again” which was desecrated and smashed to pieces in October of 2019.

There’s no need to build a labyrinth when the entire universe is one.

— Jorge Luis Borges, The Aleph (1949)

65 feet beneath Paris are 186 miles of catacombs, home to an estimated 6-7 million dead Parisians. Near the time of the French Revolution in 1780, the cemeteries above ground became overpopulated and a health problem, so it was decided to move the bones underground, some going back 1200 years.

The catacombs were created out of web-like tunnels made from mining limestone quarry pits underground, which created the buildings of Paris, and what gives them their distinctive colors. A small portion of the catacombs are still open to tourists.

In an excerpt from Underland: A Deep Time Journey, first found in The New Yorker, author Robert Macfarlane wrote about the “wondrously weird subcultures” prowling beneath Paris. This network of tunnels is described as a labyrinth of secret rooms and burial pits, with names like: The Room of Cubes, The Boutique of Psychosis, Crossroads of the Dead, The Medusa, Bunker Under the Mountain, and Room Z, an invisible city explored by a small devoted group of urban fântomas spelunkers. Macfarlane embeded himself within this subculture who are called cataphiles. He writes, “The labyrinth offered a space where Paris’s subcultures could go to grow. It became—and still is—what the anarchist-theorist Hakim Bey calls a “Temporary Autonomous Zone”: a place where people might slip into different identities, assume new ways of being and relating, become fluid and wild in ways that are constrained on the surface.”

The art and design of catacombs came to aesthetic heights with the Cappuchin monks of Rome in a series of small chapels beneath the church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini. The order is over 500 years old and holds the remains of over 4000 Cappuchin monks. Today its one of the most popular tourist sites of Rome. The museum shop beside the crypt sells postcards, tee-shirts, books, and mugs.

After Mark Twain visited Europe and the Holy Lands in 1867, he published his impressions in The Innocents Abroad where he described his visit to the Cappuchin crypt and his conversation with the monks:

Here was a spectacle for sensitive nerves! Evidently the old masters had been at work in this place. There were six divisions in the apartment, and each division was ornamented with a style of decoration peculiar to itself – and these decorations were in every instance formed of *human bones*! There were shapely arches, built wholly of thighbones; there were startling pyramids, built wholly of grinning skulls; there were quaint architectural structures of various kinds, built of shinbones and the bones of the arm; on the wall were elaborate frescoes, whose curving vines were made of knotted human vertebrae, whose delicate tendrils were made of sinews and tendons, whose flowers were formed of kneecaps and toenails. Every lasting portion of the human frame was represented in these intricate designs (they were by Michelangelo, I think), and there was a careful finish about the work and an attention to details that betrayed the artist’s love of his labors as well as his schooled ability.

I asked the good-natured monk who accompanied us, “Who did this?” And he said, “We did it” – meaning himself and his brethren upstairs, I could see that the old friar took a high pride in his curious show. We made him talkative by exhibiting an interest we never betrayed to guides.

“Who were these people?”

“We – upstairs – monks of the Capuchin order – my brethren.”

“How many departed monks were required to upholster these six parlors?”

“These are the bones of four thousand.”

“It took a long time to get enough?”

“Many, many centuries.”

Inside the Cleveland Museum of Art stands an Egyptian sarcophagus known as the Coffin of Bakenmut –one of the ancient world’s best preserved wooden coffins. Every inch is brightly illuminated with hand-painted designs and stories depicting magical prayers, talismans and rituals from The Egyptian Book of the Dead — a dense collage of images depicting a journey into the afterlife. The visual incantations bring protection and instruction for the departing spirit: a guide map for joining the gods on a final voyage across the heavens.

Imagination is an almost divine faculty which, without recourse to any philosophical method, immediately perceives everything: the secret and intimate connections between things, correspondences and analogies.

— Charles Baudelaire, writing about Edgar Allen Poe

![]()