“In the face of the Void which is truth, these glorious lies!”

–Stephen Mallarmè

Symbolism, a movement of nineteenth century art, letters, and ideas, contained many volatile and complex signs within its modes of expression. In Symbolism was the birth of the modern. The long tail of Symbolism influenced futurism, surrealism, and contemporary art forms such as performance art, experimental theatre, writing, film, and sound. The artists of that time were almost clairvoyant in their creations, and their ideas continued moving like a mysterious fog across the century.

In the 1860s, Gustave Moreau developed a visual art with hot brilliant colors and themes embracing biblical, historical, and mythological subjects—saturated with emanations of violence, erotica, fantasy, Eastern exotica, and the uncanny. Moreau’s dream-like paintings would come to visually define the Symbolist movement. In her introduction to the 1999 exhibition catalog Gustave Moreau: Between Epic and Dream Geneviève Lacambre wrote:

Moreau’s work asserts the primacy of the visual, and reminds us that pictures have the capacity to communicate aspects of human experience that cannot be put into words […] We must recall that he was motivated by a larger conceptual intention: to use color and drawing, composition and gesture—as he put it, “pure plasticity and the arabesque”—in the service of dreams and the ideal. [i]

In 1895, Moreau redesigned his home as a museum and after his death left the building and its contents of over 8000 works of art to the city of Paris where it opened to the public as the Musée National Gustave Moreau. When Salvador Dali came to the door of the museum to visit, he kissed the ground before walking inside, like returning home to the fountain of creation. Just as the Moreau museum is the concentration of one single artist’s life within Symbolism, it is also the visual nucleus of the movement, a Parisian concentrate of illuminated culture with spider-like threads reaching out to the cosmos.

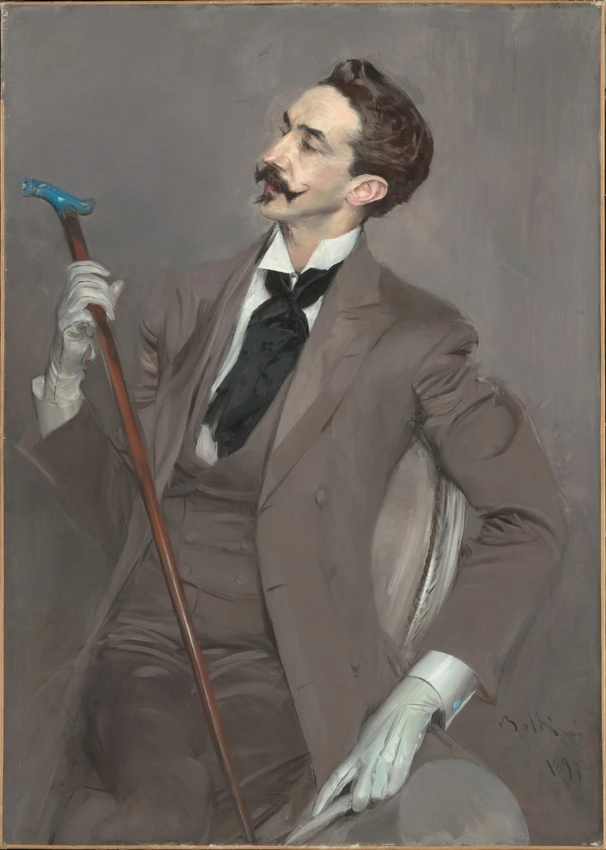

Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931)

Le Comte Robert de Montesquiou,

1897© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

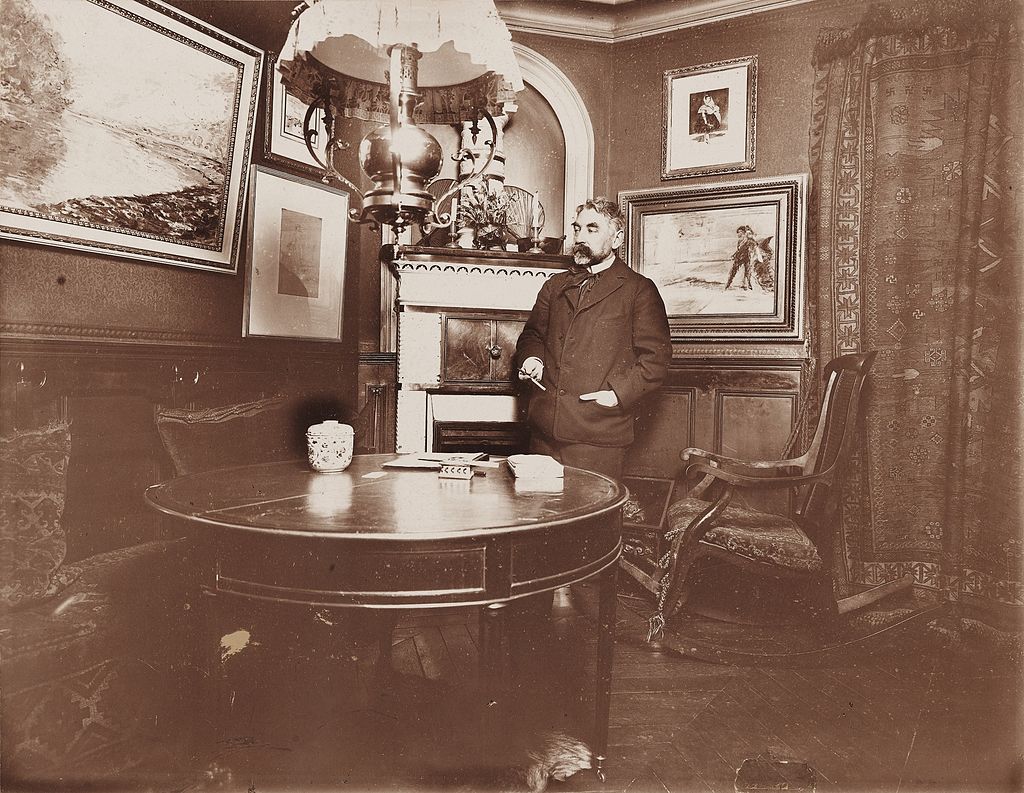

Joris-Karl Huysmans published Against Nature (À rebours) in 1885, an experimental novel of decadence set in the world of the dandy and symbolist aesthetics. Á rebours was popular and shocking at the time, centered on the wild artifice of the main character Jean des Esseintes, modeled on the real Robert de Montesquiou, a person described to Huysmans by the symbolist poet Stéphan Mallarmé, a friend and defender of de Montesquiou. Most of chapter 14 includes rapturous praise of Mallarmè which had a sudden deleterious effect on the poet and his circle, causing his immediate popularity and envy, condemning him to the epithet “decadent poet”. Shortly after the novel’s publication, Mallarmè response was his poem: “Prose (for des Esseintes)”

In chapter six of À rebours, Moreau’s painting of Salome is purchased by des Esseintes who nightly stared into the work as if in a trance. Huysmans wrote on the painting’s effect, “For the delight of his spirit and the joy of his eyes, he had desired a few suggestive creations that cast him into an unknown world, revealing to him the contours of new conjectures, agitating the nervous system by the violent deliriums, complicated nightmares, nonchalant or atrocious chimerae they induced.” The painting is described in sensual detail, like a sacred object:

The severed head of the saint stared lividly on the charger resting on the slabs; the mouth was discolored and open, the neck crimson, and tears fell from the eyes. The face was encircled by an aureole worked in mosaic, which shot rays of light under the porticos and illuminated the horrible ascension of the head, brightening the glassy orbs of the contracted eyes which were fixed with a ghastly stare upon the dancer.

With a gesture of terror, Salome thrusts from her the horrible vision which transfixes her, motionless, to the ground. Her eyes dilate, her hands clasp her neck in a convulsive clutch.

She is almost nude. In the ardor of the dance, her veils had become loosened. She is garbed only in gold-wrought stuffs and limpid stones; a neck-piece clasps her as a corselet does the body and, like a superb buckle, a marvelous jewel sparkles on the hollow between her breasts. A girdle encircles her hips, concealing the upper part of her thighs, against which beats a gigantic pendant streaming with carbuncles and emeralds. […]

Des Esseintes could not trace the genesis of this artist. Here and there were vague suggestions of Mantegna and of Jacopo de Barbari; here and there were confused hints of Vinci and of the feverish colors of Delacroix. But the influences of such masters remained negligible. The fact was that Gustave Moreau derived from no one else. He remained unique in contemporary art, without ancestors and without possible descendants. He went to ethnographic sources, to the origins of myths, and he compared and elucidated their intricate enigmas. He reunited the legends of the Far East into a whole, the myths which had been altered by the superstitions of other peoples; thus justifying his architectonic fusions, his luxurious and outlandish fabrics, his hieratic and sinister allegories sharpened by the restless perceptions of a pruriently modern neurosis. And he remained saddened, haunted by the symbols of perversities and superhuman loves, of divine stuprations brought to end without abandonment and without hope. [ii]

Overlapping the era of Moreau and Huysmans were Mallarmé’s poetic experiments and his Tuesday evening home salon open to friends, artists, and writers, mixing together, combining language, music, and visual art. Alex Roth’s profile of Mallarmé and the birth of modernism in The New Yorker spoke of this movement as a time where “the goal was to discover novel spheres of expression: the unspoken word, the unpainted image, the unheard sound.”

Mallarmé spent years writing the poem “Herodiade” (1864-1898) telling the John the Baptist story from the voice of Salome, a figure that influenced many of the Symbolists and helped to open our own twentieth century fascination with the femme fatale—an era that blossomed with the invention of Theda Bara and the Hollywood film vamp—an orientalist trope of otherness and decadence still with us today. In Guy Michaud’s study Mallarmè, he wrote;

In writing the scenario of “Herodiade” at the cost of countless meditations, Mallarmè caught a glimpse of a terrible truth: Beauty is death, or at least something analogous: an inhuman white night, similar to the starry sky where innumerable diamonds shine, useless and vain.” [iii]

In this fragment from the poem “Herodiade,” Mallarmè sets Salome communing with the infinite:

The horror of my virginity

Delights me, and I would envelope me

In the terror of my tresses, that, by night,

Inviolate reptile, I might feel the white

And glimmering radiance of thy frozen fire,

Thou art chaste and diest of desire,

White night of ice and of the cruel snow! [iv]

From reading Baudelaire, Mallarmé was aware of Tanhäuser and Wagnerian opera as “a total work of art” (a Gesamtkunstwerk in German). This idea of “totality” in art, displaying all forms of art at once, stayed with Mallarmé and became a lifelong dream, a never-ending project he referred to as The Book. His obsession to create a work of “total poetry,” a moveable, unfixed source of creation—even for all future books—helped project his image as a mystic and prophet. Notes on The Book contained ideas beyond his ability, funds, and time to complete. The poet envisioned a book composed of improvisation and movement with overlapping pages and insertions—a book set in the imagination yet always changeable. For Mallarmè, The Book as an idea was related to the flow of music, an unrealized project connected with the quest(ion) of immortality. “the book eliminates time/ ashes,” he wrote, “and the old man leaves/ existing— for it is old age— Fictive death— / as youth is fictive/ birth.” For many readers and critics, he is associated with failure, condemned for his obscurity and rejection of academics. Accepting that failure and mystery surrounds The Book is something which makes Mallarmè’s dream frustrating, but also modern beyond the imagination or understanding of our time and yet still essential.

A Tomb for Anatole was written by Mallarme after the death of his son Anatole at the age of eight. After this major tragedy, he began writing about his son’s death creating an opening for his own survival—a doorway for his aesthetic attached with emotion and direction. First published in France in 1961, Paul Auster wrote an English translation published in the Paris Review in 1980, and in 2003, New Directions published the complete work. Although uncompleted and fragmentary A Tomb for Anatole is a side of the poet rarely seen. “They are notes towards a possible poem, sketches for a work that never came to be written,” wrote Auster, “If, in spite of themselves, they carry the force of poetry, it is because they are the raw data of poetry, ur-texts of the poetic process. Beyond that, they stand as a rare example of utmost brevity wed to utmost feeling…it reveals the secret meaning of Mallarmé’s whole aesthetic: the elevation of art to the stature of religion.” Here are the opening lines of A Tomb for Anatole:

child sprung from

the two of us — showing

us our ideal, the way

— ours! father

and mother who

sadly existing

survive him as

the two extremes —

badly coupled in him

and sundered

— from whence hi death — o-

bliterating this little child “self”

During his last thirty years, Mallarmé assembled page of notes, theories, and diagrams for The Book—a literary object which is more of an artifact than a text, a collection in which words and language are discussed as a performance, or the possibility of a totally new kind of book where “the relationships between all things would be revealed.” The Book in its original Le livre manuscript is an astonishing and browsable object contained in the Houghton Library at Harvard University. A central idea of The Book was that all language was theater—connected to everything in life. In Sylvia Gorelick’s introduction to the English translation of The Book, she writes:

Indeed, Mallarmé thought of literature and theater as inseparable—a unity that culminates in the manuscript for The Book. In a letter to Vittorio Pica, he wrote, “I believe that Literature, taken at its source which is Art and Science, will give rise to Theater for us, where the performances will be the true modern religion; a Book, an explanation of man sufficient to our most beautiful dreams.” [v]

Odilon Redon, lithograph 1897. “Despite their close relationship, Redon and the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé worked together only once. Dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard commissioned the artist to produce a series of lithographs to accompany an edition of Mallarmé’s “Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard” (A throw of the dice will never abolish chance). This is one of four prints that resulted though the project was abandoned after the poet’s death in 1898. The indecipherable quality of Redon’s image matches the ambiguity of the text.”-The Met, NYC

Like Kafka, Mallarmé also disavowed his own writing and requested The Book and its notes be destroyed by his wife and daughter. In his last moments, irony and cynicism may have overcome the poet who no longer saw his work as the mystic ideal he once sought. Many of its words and diagrams were already crossed out, but thanks to the discretion of his wife and an unknown future, The Book as fragment or notes, survived. The final form of The Book will never be known as its development died with the author. In Marcella Durand’s Hyperallergic review of The Book, a pubic performance or reading is recalled as a sequence in a Fellini film:

It’s exciting to imagine, while reading The Book in all its crossings-outs, doubling backs, and stage directions, what a live reading/performance of it might be like. (A taste may be found in Federico Fellini’s film 8 ½: Toward the end, Guido Anselmi, a frustrated film director played by Marcello Mastroianni, imagines shooting himself in his despair. Then, as his enormous boondoggle of a set is dismantled, another character asks Guido, “Do you remember Mallarmé’s homage to the white page?” After that moment of imagined suicide, in that ultimate silence, Guido starts directing again. The film’s final act — a sort of public performance in which all the characters wear white — could approximate The Book beginning to take shape as a film within a film.)

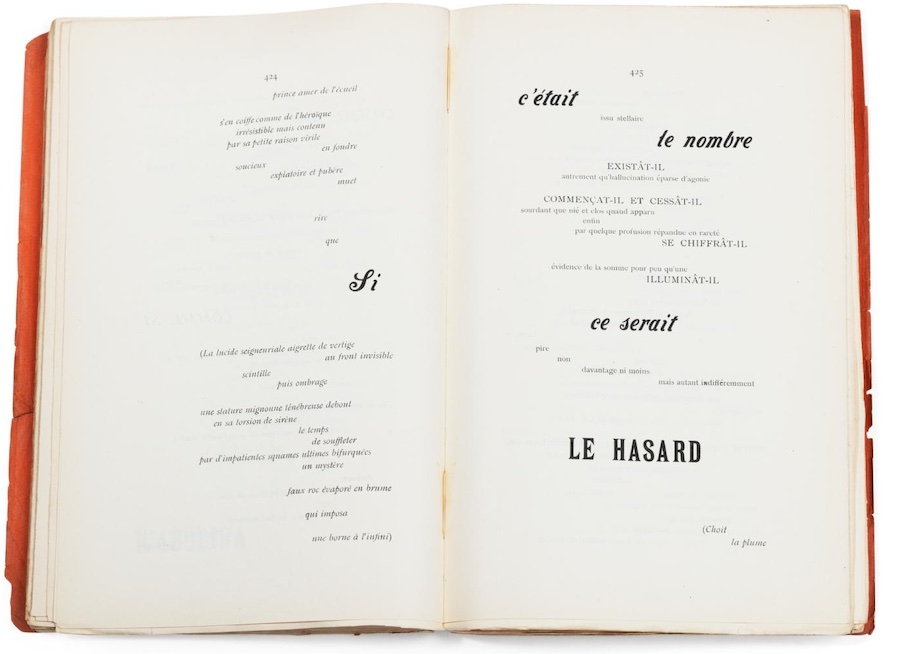

Mallarmé’s revolutionary poem “Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard” “A Blow of Dice Will Never Abolish Chance” ( 1897) spoke of time guided by chance and existential reality. “All thought emits a throw of the dice,” he wrote. Very slowly a cult of chance developed around the world, it is happening now, and Mallarmé, whose poetry was divinely guided by the stars—a “constellation” of thought, as he called it—would never accept credit for being at the center of the idea. He liked reading aloud but steered away from public attention. Two decades before Apollinaire’s Calligrames (1918) free verse was put down on the page through type and space into a beautiful vision. Mallarmè died one year after the poem’s publication and the time for tears is in focus. In Mary Ann Caws’s birthday celebration of the poet she wrote:

His poetic inventions startled everyone. The younger and adoring poet Paul Valéry wept with emotion over the poet’s notebooks of 1897, seeing the spatial excitement of the typographically adventurous Un coup de dés n’abolira jamais le hazard/ Dice thrown will never annul chance, spreading out in an unheard-of diversity of fonts and arrangements. “It seemed to me that I was looking at the form and pattern of a thought, placed for the first time in finite space. Here space itself truly spoke, dreamed, and gave birth to temporal forms.” Valéry, admiring the layout, reflected on the “reciprocity between the alphabet and the stars: ‘He has undertaken, I thought, finally to raise a printed page to the power of the midnight sky…I was now caught up in the very text of the silent universe’” [vi]

Stéphane Mallarmé: Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, France: Cosmopolis. Revue Internationale, 1897

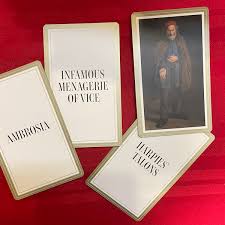

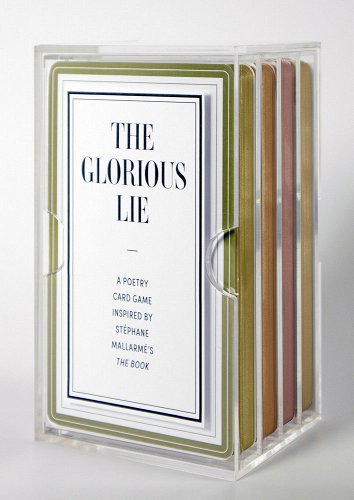

The Glorious Lie: A Poetic Card Game

Inspired by The Book (or what it could be…), the words of The Glorious Lie were taken from four Symbolist poets: Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Rimbaud, Stephan Mallarmé, and Charles Baudelaire. The words selected form a series of ideas close to Mallarmé’s heart. The project was edited by translator Holly Cundiff without comment. A mystery surrounds the cards as if they dropped from the sky. Notes in the short twenty page “instruction booklet” are brief, limited to quotations on or about The Book. It seems unlikely Mallarmé was thinking of a card decks, but a quirky logic ties The Glorious Lie to The Book which is described as a folded or cut into book, rearranged in sections or flipped through with multiple cuts in the pages like a shuffled exquisite corpse. Card decks are each a type of book container in loose multiple form, creating new books or rearrangements out of themselves, an order determined by chance. By choosing randomly, a new poem or book or thought is exposed.

Inspired by The Book (or what it could be…), the words of The Glorious Lie were taken from four Symbolist poets: Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Rimbaud, Stephan Mallarmé, and Charles Baudelaire. The words selected form a series of ideas close to Mallarmé’s heart. The project was edited by translator Holly Cundiff without comment. A mystery surrounds the cards as if they dropped from the sky. Notes in the short twenty page “instruction booklet” are brief, limited to quotations on or about The Book. It seems unlikely Mallarmé was thinking of a card decks, but a quirky logic ties The Glorious Lie to The Book which is described as a folded or cut into book, rearranged in sections or flipped through with multiple cuts in the pages like a shuffled exquisite corpse. Card decks are each a type of book container in loose multiple form, creating new books or rearrangements out of themselves, an order determined by chance. By choosing randomly, a new poem or book or thought is exposed.

The words of the The Glorious Lie are dreamlike, open-ended and reconstructed by the reader’s intention. Similar to affirmation and oracle decks, The Glorious Lie uses symbolist word combinations chosen by the reader. In a similar vein, composer Brian Eno created his own deck of intention/instruction cards called Oblique Strategies (a version now appears on the web) to randomly help overcome writing blocks and obstacles associated with music.

The Glorious Lie contains 192 two-sided oversized word cards in four sets of 48, with each deck edged in four metallic colors: silver, gold, bronze, and copper. Each set is housed in its own tightly fitted clear plexi slipcase that slides into a larger, five-sided plexiglass box. Six image cards in each deck show details from Symbolist paintings by Odilon Redon, Paul Gauguin, Berthe Morisot and others. The Glorious Lie is a well designed and curious object which looks both coldly modern and antique, a wealth of Symbolist thought echoing the decadent era.

The cards are aimed at being a literary game intended for use by artists and writers, although anyone interested in symbols, oracles, chance systems, or Symbolism will enjoy using them. The four slipcases serve as a way to separate the authors and artists into groups, but its more interesting (and closer to the William S. Burroughs cut-up method) once the cards are completely mixed together. Its easy to returning cards to their author sections since they’re edged in four metallic colors.

The Glorious Lie can be a game or method for storytelling. The reader simply chooses random cards and begins a journey. The spreads combine random words that become phrases, like a magnetic poetry game but with a darker shroud of the decadent era . By reversing the cards, another interpretation of the text is revealed. Each choice makes a “constellation”—as Mallarmè would say, when groups of words and images become a correspondent to the card thrower/reader. The cards bounce back to the reader as a story or solution. Read in this way, the four word decks are like suites in the tarot’s minor arcana organized by author, with the 24 image cards a substitute major arcana. Readings often appear intense or extreme due to the nature of the chosen authors and artists set in the 19th century, where every word and image concern sensibility and beauty. There are no rules in the Glorious Lie – its all imagination, intuition, and chance.

~Cary Loren, April 2024

Finely reproduced two-sided image cards from Symbolist painters complete the resources in The Glorious Lie. The art cards are a visual element taken from details within paintings to focus on. There no wrong way to use the decks—they are also simply a beautiful object, well made and designed to observe and hold.

The Glorious Lie is available instore or at our online gallery.

[i] Geneviève Lacambre, Gustave Moreau: Between Epic and Dream, (Princeton University Press, 1999) p.3

[ii] J. K. Huysmans, Against Nature, chapter sux, translanted by John Howard online: https://victorianweb.org/decadence/huysmans/6.html Huysmans also credits Mallarmè by name in the novel, having his main character de Esseintes who is enraptured by reading Mallarmè’s poems, “It became a concentrated literature, an essential unity, a sublimate of art. This style was at first employed with restraint in his earlier works, but Mallarmé had boldly proclaimed it in a verse on Théophile Gautier and in l’Apres-midi du faune, an eclogue where the subtleties of sensual joys are described in mysterious and caressing verses suddenly pierced by this wild, rending faun cry…”

[iii] Guy Michaud, Mallarmè, (New York University Press, 1965) p.37

[vi]Stephen Mallarmé, “Herodiade”, https://1890s.ca/wp-content/uploads/savoyv8-symons-herodiade.pdf

[v] Stephan Mallarmé, The Book, translated with an introduction by Sylvia Gorelick (Exact Change, Cambridge, 2018) p.xiv

[vi] Mary Ann Caws, “The Innovative Poetry of Mallarmé” Yale University Press, https://yalebooks.yale.edu/2015/03/18/the-innovative-poetry-of-mallarme/

A short film about the famed Symbolist poet (in the form of an interview), made by French director Eric Rohmer in 1966. The text is taken from an interview between Mallarmé and Jules Heuret published in 1891.

“I have made a long enough descent into the Void to speak with certainty. There is nothing but Beauty—and Beauty has only one perfect expression, Poetry. All the rest is a lie—except for those beings who derive their existence from the body, love, and the love of the mind which is friendship.”

—Stèphane Mallarmè, from a letter to Henri Cazalis, Selected Letters of Stèphane Mallarmè (The University of Chicago Press 1988) p.75