São Bernardo

São Bernardo

by Graciliano Ramos (Padma Viswanathan) translator,

NYRB Classics

Consider the Western. Both North and South American literatures have it: Novels of settlements, displacement and murder, (threatened) lack of law and order, rugged individualism matched to rougher fists—all at the mercy of amoral and unforgiving natural forces. Human values are thrown in stark relief; life is fought for, not a right; and people are beaten, or worse, for less than nuances of opinion.

Enter Paulo Honório, a former field hand, now in control of the estate he used to work for, São Bernardo, in northern Brazil. (Here “estate” = desolate land, feebly watered, but hundreds of acres of it.) Although São Bernardo was published in 1934, Honório is a type of man we’re already too painfully familiar with: He knows little, envies and debases the educated, does not tolerate differences of opinion, has a hair-triggered temper and violent fits; sees no reason to spend money on social services or friends or (eventually) his wife, has almost zero empathy for others, and sees himself as a perpetual victim. But his brutality is slightly moderated by the “almost” in “almost zero empathy.” Honório has his Rosebud, and he has regrets. But he knows himself well enough to realize that, if he had to do it all over again, he would change nothing. Thus, although São Bernardo is intended as ironic comedy, right now the comedy is too bitter for laughter.

French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony Patrick Chamoiseau (Matt Reeck) and Rodolphe Hammadi (photographs)

Wesleyan University Press

Devil’s Island, in French Guiana, was a notorious prison camp where the French government sent convicts from its various colonies around the world. The convicts’ forced labor was used to help expand French imperialism into Guiana, for “roads, mines, and in fields of private companies” (Wikipedia).

Patrick Chamoiseau is a Martinican novelist who, in collaboration with photographer Rodolphe Hammadi, writes on the “memory traces” of colonist history, specifically the emotional effect on Guinean culture by the penal colony’s ruins (the memory traces): the chains embedded in stone, etchings and drawing in cells, solitary confinement cells, “disciplinary” cells, freemen’s quarters, and cemeteries, whose material presence marks and embodies horrors of colonial history.

This is not a history that tries to quantify and sift among the data, but that tries to sense the historical, ambient spirit within the traces, compelled to remain there as witness to abuse in the name of progress. Hammadi’s photographs succeed in conveying the sense of place and give form to Chamoiseau’s words.

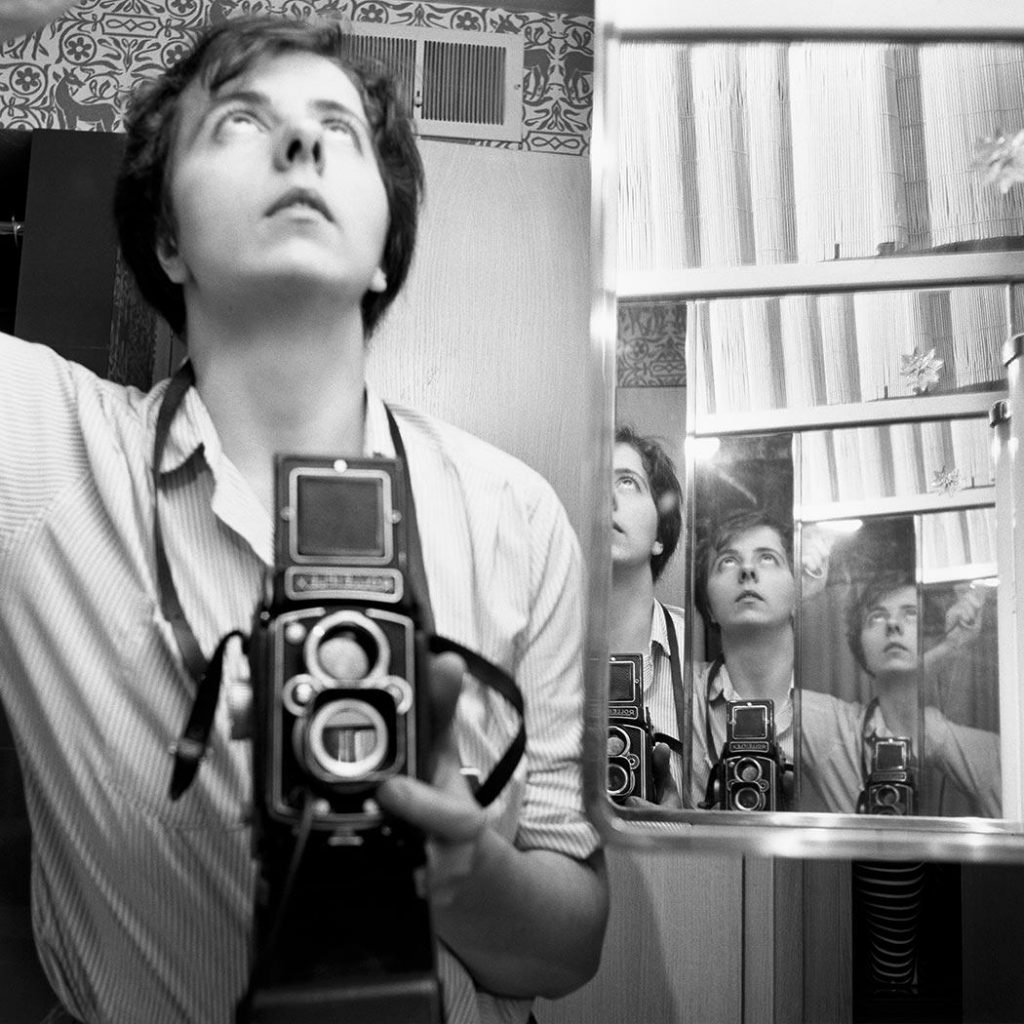

Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife

Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife

by Pamela Bannos

University of Chicago Press

Vivian

by Christina Hessleholt (Paul Russell Garrett, translator)

Fitzcarraldo Editions

I looked forward to Pamela Bannos’ biography of Vivian Maier. John Maloof’s documentary, Finding Vivian Maier, sketched the broad outlines of Maier’s adult life: The lank and aloof Maier decides early on to become a nanny to children of wealthy families while pursuing her photography habit, often while taking the children for walks. However, she is occasionally possessed of a cruel and angry streak that seems to have lead to her changing positions from one family to another, until she became too eccentric around the children to be either safe or reliable.

Forced to retire and living alone, impoverished, she becomes unable to pay the rent on the storage units she keeps her photographs in. Her properties are seized, the photographs go up for sale, and we’re back to the beginning. Who was this person? Clearly, there had to be more than Maloof was able to dig up.

Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife provides an abundance of details unavailable in Maloof’s documentary, and extends beyond it to her years of retirement. Yet it’s the abundance of details that made this biography, for me, almost unreadable. This is the sort of writing that wants full value for all research done, even if 90% of it is trivial or irrelevant.

We find out, for instance, about distant cousins who lead fabulous lives or meet fabulous people, or friends of friends who lead fabulous lives or meet fabulous people: all as an attempt to insert Maier into a milieu of talented, influential doyens—so that Maier’s greatness comes with an implied seal of inevitability: partially inherited, partially environmental—What’s a girl gonna do? But once the six degrees of Kevin Bacon are peeled off, the remaining reality is—as amply detailed by Bannos—Maier grew up desperately impoverished in a desperately dysfunctional family. Raising other people’s children and taking pictures on the side sounds like a sober, if unambitious, way out of her predicament.

During her decades as a nanny, Maier silently amassed a collection of 150,000 images, most of which she never developed. Based on the evidence of the four or five books of Maier’s photographs I own, her eye and sense of composition almost never err, nor do the great range of humanity and empathy her subjects convey. That may be the edited, best version of Maier’s talent (with more books of previously undeveloped images presumably to come), but it’s still a formidable talent, and the fact that the talent went unshared and unknown still amazes: Who was this person?

Bannos clearly did a lot of legwork for this book, and it may be the only biography of Maier available for a while. (The undeveloped rolls of film may reveal more about her yet.) Bannos isn’t a prose stylist —the sentences plod along like cement shoes. But plodding sentences are one thing; I just wish her editor had been more ruthless in demanding concision, especially when the prose isn’t making the life interesting.

While Christina Hesselholdt succeeds in re-telling Vivian Maier’s life story in a way far more engaging than Bannos’s biography, Hesselholdt hasn’t succeeded in creating an intimate inner life for Maier.

The problem for Hesselholdt and Bannos may be that, apart from Maier’s self-portraits, Maier the thinking artist remains as mysteriously aloof as ever—no diaries, no correspondence—only the memories of her by the families she worked for. Hesselholdt’s Maier assiduously avoids discussing her inner life, as well might have Maier herself. But the result is a biography told in the first person.

Girl Pictures

Justine Kurland

Aperture

Photographer Justine Kurland staged from 1997-2002 a series of photographs showing small groups of teenage girls vagabonding and hoboing across the country as runaways leading rough-and-tumble lives. The results are a portfolio of color photographs as classically composed as any Renaissance painting, and a beguiling sense of remembering what it was like when every experience was new and independence meant danger and success required friendship.

Girlhood Across America Captured by One Photography; a gallery of images; New York Times

The Lawless Energy of Teenage Girls, –The New Yorker

Stockhausen Serves Imperialism

by Cornelius Cardew

Primary Information

Essays on composers and composition by the British composer Cornelius Cardew, circa 1974, are more interesting for their tone of anguish, righteous anger, and drive to moral good than as slices of Marxist dogma, which both impels and drags down his discussions of what compositions “ought” to do, and which composers have “failed” to do so. John Cage is chastised for introducing into music bourgeois notions of anarchy, and Karl Heinz Stockhausen for bourgeois notions of mysticism.

Being a Communist in good standing, Cardew both quotes Mao on “correct” ideas regarding music and denounces his own previous works. (Such Maoist self-denunciations later became absorbed by capitalist corporations and academia, which renamed them “performance reviews.”) But with ideological rigidity comes blindness to see in oneself the faults one intolerantly points out in others. The assumptions Cardew makes—on any given point—go unexamined, and answers are known before (or without) being proven.

There is no joy in the music—intellectually or emotionally, via performing, composing, or listening—just the relentless shame at having not having connected with proletariat audiences, who tend to be put off by all the discussions that must occur before, during, and after each musical performance to assure it has been “properly” contextualized and understood, etc. As Brian Eno reportedly said at the end of a (non-Marxist) music conference a couple of decades ago, “So many theories; so little music.”