Tom Bowden is a reviewer of small press, eccentric, literary, and independent publishers featured in his monthly column I arrogantly recommend…. His recent “Year-end Favorites” was emailed from China where he’s a part-time educator in English.

Book links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If titles are out-of-stock or unavailable online, please call or write and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: I arrogantly recommend… Thank you for your support of small press books.

Lies and Sorcery

Lies and Sorcery

Elsa Morante / Jenny McPhee

NYRB Classics

Originally published in 1948 and now finally available in English in complete form—in a superb translation by Jenny McPhee—Elsa Morante’s debut novel, Lies and Sorcery, is told by a young woman named Elisa, a reclusive but highly imaginative narrator who serves as her parents’ biographer. The premise of Elisa’s story is that everyone lives some type of lie, and neither her deceased parents nor her caretaker (the woman who takes Elisa in after her parents’ death) or her friends were any different. Unlike actual people, however, her fantasies never betray her—and in that regard, she is very much like the other women in her life.

Elisa begins her family saga with her grandmother, Cesira, who marries a man twice her age, Teodoro Massia, the disowned, wayward scion of a wealthy family who pissed away all his money on travel, drinking, and women. When the prim and proper Cesira realizes her matrimonial mistake—with no one to guide or look out for her—she is furious and disappointed. While Cesira’s daughter, Anna (Elisa’s mother), is adored by Teodoro, Cesira sees her daughter as yet another burden to endure. Raising Anna in poverty, Teodoro regales his daughter with tales of his former trips abroad, and she cultivates a yearning to travel herself.

Teodoro’s sister, Concetta, who remained in good graces with her family and married well, is a countess whose husband died prematurely but not before their conceived a son, Edoardo Cerentano, a spoiled, manipulative and dissolute fop allowed to get away with anything he wants to, and deeply insecure and resentful because of that indulgence. Early in Anna’s life she meets Edoardo and falls in love with him, a love wholly unrealistic since it is in part aspirational on Anna’s part: The hope that her wealthy cousin will marry her and relieve her of the destitute life her father’s irresponsible decisions condemned her and her mother to. No amount of debasement and manipulation of her on Edoardo’s part will free her of that delusion.

Enter Nicola Monaco, an accountant for the Cerentano family, whose management of their financial affairs only increases after the death of Concetta’s husband. Part of his duties include collecting various fees from families that tend land owned by the Cerentano family, including the honest and hard-working Damiano De Salvi and his young wife Alessandra. Like Teodoro Massia, Nicola Monaco is a teller of tall tales and a philanderer. He ends up seducing Alessandra, who eventually gives birth to his son, Francesco. Francesco is a bright, precocious boy, the smartest child in a remote, rural community, and is dandled by Nicola on his rare visits to Damiano and Alessandra. Alessandra harbors hopes of greatness for her son, whom she hopes is worthy of Nicola’s attention and presumed fortune. However, Nicola is caught embezzling money from the Cerentano family and ceases visiting Alessandra and Francesco. Alessandra and Damiano, who know nothing of this, spend all of what little money they have on Francesco’s education, and Francesco does well enough in school to go to college in Sicily.

Once in Sicily, Francesco—the smartest kid in his Podunk town, utterly full of himself, and affecting a title of “baron”—Francesco hopes to track down Nicola for money to attend college. Nicola is dead by this point, but he does manage to meet Edoardo. Edoardo in turn introduces him to Anna, whom he is trying to dump, and Francesco of course falls madly in love with her.

But as Elisa tells us at the novel’s onset, she is not a reliable narrator. Inventing tales is a talent she honed to deal with her own isolation amid her parents’ emotional upheavals and mutual antipathy. Given that she was only 10 when her parents died, and that her caretaker, Rosaria, is not family, Elisa has no way of knowing her parents’ history. As plausible as it is, the novel is therefore a history invented from what she could plausibly surmise from her grandmother, Cesira, her parents’ behavior, and what she could guess of her father’s relationship to Rosaria.

A couple of themes emerge during the telling of this near 800-page story: Mothers’ antipathy towards their daughters and mothers’ adoration of their sons, both with disastrous consequences for the daughters and sons. Anna, Elisa’s mother, is addled and living in a willfully sustained hatred of the world because Edoardo dumps her after a year or so of mercilessly manipulating her and endlessly lying to her about his affections for her. She never overcomes her heartbreak, never once shows any interest in overcoming her heartache, and instead chooses to live in a delusion in which he would one day return to her. Meanwhile, utterly impoverished, she agrees to Franscesco’s marriage proposal so that she and her mother, Cesira, can eat and have a place to live. (She sees herself as too grand to ever work and would rather die before ever doing so. She lives the remainder of her life barely surviving, even when married to a man who works endless days, six days a week.)

Elsa Morante—and through her, Jenny McPhee—develop a pair of protagonists, Anna and Francesco, who begin as lively spirits that are slowly ground down to abject bitterness as their dreams—some more realistic than others—are reduced to ashes, their impoverishment only worsened, while they cling to hopes with no basis in reality. Only the courtesan Rosaria, the giddy, flighty, and idiotic lover of Francesco, is possessed of a life-affirming version of constancy, as corrupt as that word may be given the life she leads. The characters are as endearing as they are maddening.

I generally stay out of the prediction business, but Jenny McPhee’s utterly compelling rendition of Lies and Sorcery seems certain of being nominated for—and winning—any number of translation awards next year, a masterpiece of the art of translation.

Shimmering Details, Volume 1 & Volume 2

Shimmering Details, Volume 1 & Volume 2

Péter Nádas / Judith Sollosy

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux

Hungarian Péter Nádas—novelist, photographer, and journalist—has managed to live through interesting times. Born in the midst of WWII, his hometown, Budapest, was bombed by both German and Russian armies; he witnessed Stalinist purges on the fringes of the Soviet Union, involving infighting (and fatal betrayals) among Hungary’s Communist Party members; government collapse, violent revolution, and restored oppression; harassment by undercover agents for suspect behavior; and more. Born into an affluent Jewish family whose immediate and extended members were involved in national conservative-liberal Hungarian politics going back four or five generations, almost all of whom were writers—historians, poets, novelists, and translators. It’s no wonder the family library was such a treasure for the young Nádas.

Nádas nevertheless began attending Calvinist services as a child, under the wing of one of the family’s maids, and to the chagrin of his godless communist parents. (Attending Calvinist services was no childhood whim—Nádas states that in late middle age he took up studying Calvinist doctrine in earnest and formally confessed his faith as a Christian.)

Beginning with his memories as a toddler during the Second World War—during the bombing of the apartment his parents lived in— Shimmering Details includes summaries of interviews with family members decades after the events and the reading of both contemporary official accounts and memoirs written years after the events, in an attempt to attain the truth regarding various wartime and later political efforts that included his parents and relatives. Here is an autobiography by an author whose conscientiousness and ethical values require him to question the trustworthiness of his memory, to see if he can square his memories with other accounts of the same events.

The bombing of his apartment building at the beginning of Volume 1 finds him—aged two—in the arms of his mother as a brick wall falls upon them. Later events, when Nádas is aged three or four, include his father’s conscription by Germany as a prisoner of war, used for his engineering skills and as a spy (along with several of Nádas’s relatives) for the illegal Hungarian communist party. (After the war, the willingness of these party members to lie—even about other family members—in order to protect themselves and betray others (including family members)—is a side-effect that Nádas notes is all too common among authoritarian ideologists.) Despite, or because of, the emotional turmoil one might imagine the war and its lingering aftermath might inflict on any sensate person, Nádas sees himself in retrospect as autistic, someone for whom a wide range of emotional reactions made no sense—perhaps in part because of the monstrous hypocrisies he saw adults engage in all his life, and in part to the rational, even-toned explanations they provided young Péter with, from his father’s descriptions of the principles of physics to his mother’s adjective-free description of the six months of torture young Péter’s father experienced as a prisoner of war:

As if my mother had meant to prepare me for something quite matter-of-factly, something that a person can hardly avoid in life, interrogation under torture. This intermittent half a year included electric shock to the genitals, electric shock in water, which I remembered very well, because I didn’t understand it, but my father explained in detail how and why certain materials such as the mucous membranes amplify electricity and how the body can be made to conduct it, how the positive and negative poles of electrical energy function; it was Sunday when he explained it; and also beating the shoulders and the head with truncheons, and then the so-called talpalás, the beating of the soles of the feet, the knocking out of the teeth, being spread-eagled, being hung up, the repeated and deliberate ripping open of scabby wounds, standing you up against the wall, and so on. So that I’d understand electric circuits, he even had electric current strike me. Let it be said in his defense that back in those days they hadn’t amplified the voltage to 220 volts yet, though the 110 volts gave me quite a shock, too. In the autobiographical sketches he wrote for the benefit of his comrades, perhaps he held off revealing the temporal lengths and means of his interrogations under torture because by relating the story of his physical trauma, he’d have called attention to the helplessness of his situation.

Readers encountering a two-volume work clocking in at about 1,100 pages, written during the author’s 74th year and labeling itself a memoir, well, such readers might expect such superficialities as photographs and chapters organized according to key events. But not only are there no photographs and no chapters, this memoir doesn’t even have breaks between (typically two-and-a-half page-long) paragraphs to indicate a change in time or scene. (Although there are two paragraphs ending with suggestive ellipses. Judith Sollosy, who translated both volumes, had a real workout presented to her, which she deftly mastered.) Nor is it chronological or comprehensive, covering only the roughly dozen years between the author’s ages from two to 14—from the time his parents’ apartment was bombed during WWII until their deaths (his mother from cancer, his father from suicide) before the October revolution of 1956, which failed in its one coherent aim—independence from the Soviet Union. Nádas’s approach to the story of his life follows a series of concentric circles leading, over the years before and after his birth, up to and away from personal, national, and world-historical events.

Hundreds of pages throughout the two volumes are dedicated to his forbears and friends of his family. Volume 2 begins with his search, as an adult, for a concentration camp in France along its border with Spain at the Pyrenees, a camp almost entirely forgotten because its internees comprised communists and anarchists who fought against fascist forces in Spain. Nádas’s father would have been among their number if not for a medical condition, but Péter Nádas did have an uncle who spent some time at the camp before escaping, and many of his father’s friends died there. Those who managed to escape were not seen as heroes, however. During WWII, Hungary’s Communist Party (which Nádas’s parents faithfully served) was illegal, and members risked their lives fighting Nazis there. But Party members who survived arrest and interrogation at the hands of the Nazis were often later tortured and killed by the same Party they served under the rationale that the only reason the Nazis hadn’t killed them was because they had ratted out other Party members. And for that alleged betrayal, the Party would finish what the Nazis began.

Stalin’s paranoid purges in Russia found their counterpart in Hungary, where Communist Party members could not betray each other fast enough, especially if they felt it would save their own lives. Hypocrisy and duplicity reigned in Hungary’s government for decades after the war. Nádas at an early age became quite sensitive to the abuses to which logic and language were put in the name of the Party, whose existence took precedence over mere human life.

The series of renunciations made it quite clear what constitutes the set of conditions required by opportunism and collaboration, what the sentimental use of language is a substitute for, and what it is meant to hide behind this spellbinding sleight of hand. To hide and reorchestrate, through the manipulation of language, offenses against others in the interest of preserving one’s desirable self-image.

Lacking political representation, those who at that moment were Jews or who, despite their intentions, suddenly counted as Jews, found themselves up against an armed and bureaucratic apparatus that would not tolerate or acknowledge representation of any kind. A nation, too, is also invariably the fiction of others.

Driven and repulsed by what he witnessed, Nádas’s hatred of all forms of tyranny has given his Calvinist theology an interesting shape.

The God we have will effectuate every act of every individual without the least scruple, and in this he is an almighty God indeed.

A person who serves this God must make sure of just one thing, that he should have no self-imposed ethical or psychological obstacles stand in his way, that the Irish Protestants should not be prevented from slaughtering Irish Catholics with reference to Jesus Christ, who themselves are slaughtering the Irish Protestants with reference to Jesus Christ, that there should be no obstacle to prevent the Croatians’ own god from slaughtering the Servs in the name of Jesus Christ. And lest we forget, according to Canon Law, the pope prays for the salvation of the murderers and not their victims, whereby he encourages the freedom of action of survivors. The silent clamor of the dead has not yet reached his most holy ear; what’s more, he must turn off his hearing with his consciousness, which he calls faith.

Shimmering Details is a vital record of historical facts and human cruelty demonstrating the falsity behind the notion that individuals are separable from the cultural ideologies they are born into.

Poguemahone

Poguemahone

Patrick McCabe

Biblioasis

Pogue mahone—an Irish term for “kiss my arse”—was of course the original name of Shane McGowan’s band, which he shortened to The Pogues. In that spirit, Patrick McCabe’s Poguemahone is a novel-length poem about a pair of bastard siblings, Una and Dan Fogarty, hapless and scrappy Irish children of the unwed Dots Fogarty, whose suicide leads to their being raised in an Irish orphanage / foster care system that seems to blend the worst aspects of juvenile prison with factory work. The book mainly focuses on their later lives in the early ‘70s, when the obese Una is in her 20s and free of the orphanage, living for the summer in a hippie squatter commune where—among the dope, liquor, acid, and changing personnel—she falls in love with one Troy McClory, a college drop-out and Ian Hunter / Mott the Hoople wannabe, who gives her the attention she otherwise never received or receives, including the occasional beating.

Una’s brother, Dan Fogarty, narrates the story, but at some point in the telling, one notices that certain facets of the Dan-POV don’t quite add up—certain bits seem to belong to the domain of an omniscient narrator—until one’s hunches are confirmed (spoiler alert) that Dan is actually a gruagach, an Irish sprite, invisible and unheard (to all but Una), with poltergeist-like abilities to move objects—such as pushing out the window a competitor for Troy’s attentions. A gruagach embodies a soul—in Dan’s case his soul was limited to the few drops of blood that dripped from his mother’s uterus after a botched abortion—him—while she hanged herself from the rafters.

Poguemahone, for all its bleakly comic episodes, is more seriously about the tensions between traditional and modern ways, trust and betrayal, memory and vengeance, and British / Irish power dynamics.

Novel Explosives

Novel Explosives

Jim Gauer

Zerogram Press

Novel Explosives is a philosophically rich novel of ideas occurring during a recent Easter week, exploring the ongoing rift between reason and sensibility; identity, responsibility, and redemption; and the ethics and materials shaping the practices of venture capitalism, physics, and medicine. Three narrative strands unite a simple storyline: one strand is narrated by an amnesiac with little money in unfamiliar settings; the second by a venture capitalist whose latest start-up has gone disastrously wrong, with substantial amounts of missing cash; and the third an omniscient narrator describing a pair of henchmen for a drug lord who confront endless obstacles executing a simple assignment.

The geographic site where these three strands meet is Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, currently Hell’s largest branch office in North America, where the forces of reason in the name of capitalism and military efficiency unite, exporting to the world goods the city’s factory workers will never afford and drugs Americans won’t live without. If that sounds like a bummer—it is—I’m way ahead of the story, which begins with a curious mystery.

The narrator of strand one wakes up in hotel room in a quaint town called Guanajuato, Guanajuato—a place he has no recollection of. In fact, he has no recollection of anything personal related to himself or his experiences, including his name. He is able, however, to recall facts but not where, how, or why he learned them. When checking his mind for areas of knowledge that seem particularly deep, he finds that he knows much about finance and its regulations; otherwise, he seems to be a reasonably educated soul. One clue to his situation is the “large painful knot, the size of a baseball cut in half, on the back right center of the top of my head.”

The narrator, looking around his hotel room, discovers a wallet with an ID card—apparently his—whose photograph is an 80-year-old picture of the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, and whose name and address are those of one of Pessoa’s heteronyms, Alvaro de Campos, which only further confuses the narrator. Is this supposed to be him? He has only a 1,000-peso note and an ATM card whose PIN he is unable to determine from among the dozens of other number sequences he discovers he has also memorized.

Tying the other threads together concerns the rest of the novel, which—for comparison’s sake—involves inept Elmore Leonard-type crooks meeting moral principles from Coen Bros. films, as told by David Foster Wallace waxing ironic at length but with all the footnotes integrated into the body text.

What poetry after Auschwitz, when uncommonly cruel drug lords, who are also big Wall Street investors, can quote Shakespeare? Gauer holds out a sense of potential redemption for us—if we stop before the bill comes due for fulfilling our material wishes at all costs.

Or, put another way: How much do you know about face transplants?

The Logos

The Logos

Mark de Silva

Clash Books

The Logos is a Faustian tale about an artist—the unnamed narrator—midway through life’s gloomy wood whose girlfriend of two and a half years, Claire, leaves him shortly after he decides to quit the world of gallery shows and the rigamarole that accompanies it. But he has bills to pay and has sold the last of his pictures (of Claire), so is at sea with what to do next.

Enter James Garrett, owner of several companies involved in materials science and engineering, and presumably worth billions. He has several products in development for which he would like to develop a stealth ad campaign: a whiskey, a sports drink (along the lines of Gatorade but with a kick), and sunglasses. Will the narrator, the pure artist, succumb to working in the realm of crass commercialism? Garrett offers the narrator carte blanche to buy whatever materials and experiences he needs to get the job done. All the narrator has to do is trade his freedom for joys.

The Logos is one of the finest novels I’ve read in the past couple of years, along the lines of Jim Gauer’s Novel Explosives in its insistence on exploring motivations and choices regarding significant ethical issues related to satisfying self-gratification.

The English Understand Wool

The English Understand Wool

Helen DeWitt

New Directions

This funny novella—it’s only 69 pages long—reads like an homage to French Nobelist Patrick Madiano, who obsessively returns, in his own short novels, to a youth being raised by a shady couple more often absent than not and aloof when home. In the case of Wool, Helen DeWitt’s heroine is a 17-year-old young woman trained and raised by her Maman to have impeccable taste in all matters and behaviors, accompanied by a serious grounding in piano performance. Her upbringing is international, with mansions, vacations, and shopping sprees across multiple continents.

The book’s pivot: Returning to the hotel suite she and her mother have been sharing, the girl discovers the room empty of her mother but filled with police. Maman and father are on the run. Moreover, Maman and father—or, rather, the couple who raised her—are not her parents. Instead, they stole her as a baby at 18 months and somehow got hold of her $100 million fortune. And her real name is Marguerite.

How Marguerite reacts to the news—and the loss of her fortune—says something unexpected but logical about being a person of wealth and taste.

Invisibility: A Manifesto

Invisibility: A Manifesto

Audrey Szasz

Amphetamine Sulfate

Audrey Szasz is the real deal: An intelligent, confident, and unsettling writer using a wildly unreliable narrator presented under her own name but with the addition of a doppelgänger named Nina—a high-priced, underaged call girl pimped by a woman referred to as Mother, described as one might imagine Jeffry Epstein’s girlfriend, Ghislaine Maxwell, to be. Mother keeps Nina under heavy sedation to keep her from minding the life she is subjected to—the sexual plaything of the wealthy and cruel. And the life she is subjected to has led to Nina’s emotionally dissociation from it and notions of morality and empathy. Her dissociation preserves her from killing herself. Other writers, such as Beryl Bainbridge and Helen DeWitt have hinted at the sadism of Britain’s wealthy, and Henning Mankell and Stieg Larsson have graphically described the sociopathy behind the staid respectability of Sweden’s fortunate ones, but Szasz deploys an unwilling accomplice to such crimes, ranging from acts of S&M to serial murders. It’s a lot to pack in under 50 pages, but Szasz does so deftly.

Seriously Well

Seriously Well

Helge Torvund

The Song Cave

The joys of reading, creating, and living, considered under the duress of a recently discovered tumor. Seriously Well is avowedly joyful and appreciative of the “enigmatic art” of writing—“signs / resembling tiny insects,” that “can make the outer world / and the inner imagination / meet.” Writing allows us

To be in contact

with another human being’s

mind, visions and feelings

through letters.

As if a letter

was a magic wand.

Perhaps

the enigmatic in this

is what keeps me

going.

The feeling that such

an almost impossible thing

really can happen.

That by using the language

in a certain way,

you can establish some kind of

direct contact

between that which is existing

in you and that which exists

in another person.

A more laudatory appreciation of literature’s work I can’t imagine. But its admirable achievements are tempered by the fact that, alas, we don’t have world enough and time to explore them all: Time enters the picture, forcing us to realize the limited period we are granted to appreciate creation.

I suddenly became

completely aware of

the fact

that Death always walks by my side.

I stretched out my hand.

I said: OK; so there you are then.

I might as well shake hands with you,

and accept that you are here.

In this way I included Death in my life.

The gift of creation, in Seriously Well, is represented by a jazz pianist’s improvisation:

Now.

This is the moment.

When your fingertips

meet the keys

nobody knows what

is going to happen.

It’s crucial to point out that, in the moment of creation, “nobody”—including the pianist—”knows what / is going to happen.”

You put your fingers down

and the world is black and white.

And from the black and white

you start to create

colors.

All the sounds

all the tone colors

from green to blue

and from grey to

yellow.

Then, in light of these boundless enthusiasms of color, the diagnosis of a tumor.

A feeling that told me

that when it is darkening around the heart,

and the time is shrinking,

you have to embrace the fear

and give yourself over

to an insane confidence.

A beautiful, sustained meditation on the life-enriching and -affirming places where “the outer world / and the inner imagination / meet.”

Whale

Whale

Cheon Myeong-kwan / Chi-Young Kim

Archipelago Books

Long-listed for the International Book Prize this year, Whale is Cheon Myeong-kwan’s first novel, a multi-generational story detailing the lives of three women—grandmother, mother, and daughter—from Korea’s lowest social class, demonstrating resilience, cleverness, and loyalty in the name of survival in a poor, rural, and heavily patriarchal society that has little but contempt for females.

Imbued with a sense of the mythical and archetypal—a sense of embodying eternal truths— Cheon endows his characters with extreme qualities (the most this, the least that, and something mysterious and transcendental in between (often sex and love), including the situations they find themselves in). The situations, too, often end up illustrating some eternal “law” regarding everything from physical to social mores. Thus, the novel’s actors seem as fatally flawed as any protagonist in a play by Aeschylus. Most of Whale’s action follows the ups and downs of the middle woman, Geumbok, and her daughter, Chunhui.

Geumbok has a natural eye for efficiency, a skill she deftly employs with the menial workers she first takes up with. She’s a natural beauty possessed of a scent that drives men wild. Through sex and hard work, Geumbok rises economically and socially. Her biggest break comes with an idea for a brickyard after meeting a man with an excellent sense of the materials needed for making excellent bricks. As her brick business booms, Geumbok applies her fortune to building a movie theater.

At some point during the years, Geumbok gives birth to Chunhui, a large, inordinately strong and ugly girl whom Geumbok roundly ignores. Chunhui’s inability to speak and her slow ability to think leaves her almost entirely friendless and abandoned, even while her mother’s fortunes increase. In fact, Geumbok’s body eventually transforms into that of a man’s, and he (no longer she) has replaced “The strong, kind, confident woman she had been” with a “small-minded man, filled with selfish impulses and vengeful thoughts.” Having either betrayed, killed, or otherwise sold-out any friend or lover they ever had, and having only ever ignored their child, Chunhui, what sort of fate could Geumbok possible face?

Chunhui lands in prison for a crime she didn’t commit and eventually returns to mother’s long-abandoned brickyard, living on wild plants and animals and manufacturing bricks again, just to pass the time. What point could there be in such a life? The answer suggests one reason this novel was nominated for a Booker Prize.

Across My Big Brass Bed: An Intellectual Autobiography in Twenty-four Hours

Across My Big Brass Bed: An Intellectual Autobiography in Twenty-four Hours

Gary Amdahl

corona/samizdat

Barceloneta, November 28th, 3:00 AM, fine rain, high as a kite

I drove, aimlessly but alertly, fighting traffic around the basement. I pressed the big red plastic button in the middle of the knurled steering-wheel with the heel of my palm, but the horn didn’t work. . .

So begins Gary Amdahl’s excellent intellectual autobiography, Across My Big Brass Bed, 24 chapter-paragraphs across 288 pages. It took me a moment, however, to realize that the date and time listed do not coincide with time the narrative description begins. Gary Amdahl is not a stoned adult driving around his basement, crammed into a plastic car for toddlers. He’s a more-or-less regular guy, a 60-something simply recalling his childhood, born toward the end of the Baby Boom to a prosperous couple.

“Sensation and Catastrophe”—a phrase Amdhal uses several times throughout Brass Bed—could serve as the book’s alternative title. As an autobiography, it comes up short, chronologically, since most of its key events occur by the time Amdhal is 19, i.e., in the mid-1970s. Less a full-on autobiography and more a confrontation with the life-changing and life-awakening influence of his first lover, the improbably named Karla Popper, who embodied eros and intellectual pursuit as inseparable versions of each other, spurring Amdahl’s own incipient interests in a life of the mind and body before she disappeared from his life and before he could understand the sensations and ideas she aroused in him and integrate them into a harmonious rather than discordant whole, which is what he has become. Plenty of sensations here, and plenty of catastrophes.

Karla Popper was his social studies teacher, she 28 to his 14. Presumably dead from an illness she didn’t want Amdahl to know about until afterward. But before dying, she introduces him to varieties of sexual pleasure alongside the works of Karl Popper (of course), Martin Buber, and other intellectuals popular in the late ‘60s. He’s a smart kid without direction: an “A” student, a first-chair flutist with private lessons and a strong interest (and ability) in playing baroque music, a kid with a drive to live a life of the mind—and engage in competitive motorcycle racing while stoned.

Amdhal reacts to Karla’s death by spending his summer mowing lawns and tripping on hallucinogens. His parents’ divorce exacerbates his sense of estrangement from his social milieu. He begins seducing girls his own age and making deeper forays into drugs and danger during his high school years. And after high school—well, he just needs to get out of town.

So he leaves the state (Minnesota) and heads out to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he hooks up with a motley group of current and former cycle racers. Among this group of men in their mid-20s, who seem impossibly grown up to compared to himself, Amdahl’s 19-year-old brain slowly begins to develop a broader understanding of his frenetic self, a sense that eventually comes to a point of simultaneous im- and ex-plosion emotions brought on by an admixture of drugs, alcohol, mourning, and the undigested forces of literature, music, and motorcycle racing. What changing his life requires takes Amdahl over five years of ruthless self-examination to figure out, with Across My Big Brass Bed the amply rewarding fruit of that discovery. Strongly recommended.

While We Were Dreaming

While We Were Dreaming

Clemens Meyer / Katy Derbyshire

Fitzcarradlo Editions

When the Berlin Wall falls, a group of boys—Daniel, Rico, Paul, Walter, and Mark—are 13 years old and living in a poor quarter of Leipzig—that is, living on the East German side of the wall. The notion of “liberation” is not part of their world view, and the wall’s fall does not bring about immediate economic prosperity to those born and raised in the German Democratic Republic. Its industries are Soviet-era, devoted to producing cheap, poorly made and designed goods no one has use for, especially now that citizens can buy better-made goods from the West.

Before the fall, when the boys are around 8 years old, their fathers have jobs, often as skilled laborers. But the fathers vanish along with their jobs, and by the time the wall comes down, parents—fathers and mothers—are well into alcoholism, regularly engaging in physical abuse of each other and their children. Chronologically, the major events during the 10 years or so covered by While We Were Dreaming go as follows: Industry leaves, families dissolve, the wall comes down, schoolrooms shrink as students and their parents leave for the West, and those left behind form gangs, leading to juvenile jail, adult prison, and death (although death often comes before prison).

Coming into Leipzig with the wall’s fall are pornography, better-quality cigarettes and alcohol—and heroin, pills, and cocaine. As in Scorsese’s Goodfellas, the boys’ sordid lives only worsen once hard drugs become available. But before the hard stuff kicks in, the teenage boys are content with smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, and beating up members of competing gangs. In the space of a just a few years, the 13-year-old boys transform from cute with rough-and-tumble edges, to unemployable violent criminals with drug and alcohol problems, finding themselves in and out of hospitals, drunk tanks, and jails by age 16.

Daniel Lenz is the novel’s moral center—or as moral as conditions in his neighborhood allow a person to exhibit and remain alive. But of all the characters, he is the one who tries to stop or avoid fights with other gangs, to stop or avoid robberies, beatings of parents who beat their children, and so forth. Before Germany is reunited, he is an academically promising lad and patriotic Young Pioneer; after its reunification, he becomes a hapless observer of his and his friends’ declines into mental illness and death.

Dreaming’s nonchronological structure builds upon the emotional impact of what the boys endure. Rather than lead anarchic lives filled anomie and violence, they (individually and collectively) would prefer goals, responsibilities, and recognition. To that end, at around age 15, they create a techno club in the shell of an abandoned factory, decorating the walls and stairwells with reflective tinfoil and little lights, setting up a makeshift bar, and hiring a DJ whose fans span gang affiliations. But the club ends up being destroyed by a jealous gang from another neighborhood. On another tack, one boy adopts a dog and devotes his energy and money taking care of the dog, even ensuring its health to the care of a vet—all at the expense of the alcohol and cigarettes he would otherwise buy. That, too, comes to a bad end. Another of the gang, Rico, hopes to become a boxer and trains diligently for the opportunity, but those dreams are quashed as well. Collectively and individually the boys’ hopes for a sense of dignity and self-respect are crushed at every turn. There is no room for solace in their world.

By the time the Dreaming ends, only Rico and Daniel are left standing, Rico on his way to a lengthy prison sentence, Daniel desperately trying to keep his full-time job, not break his parole, avoid violence, and salvage of himself what he can to give shape to something like hope.

Brian

Brian

Jeremy Cooper

Fitzcarraldo Editions

Brian tends to reticence and caution in personal and social interaction, an inborn temperament only exacerbated by his parents’ bullying and debasement, intended to toughen him up during his childhood in Northern Ireland. Free of their grip—his mother’s death when he is 16 and his estrangement from his father and older brother—he moves to England, becoming a file clerk for Kentish Town, a position he holds for the entirety of his professional career. Ever shy and awkward, always fearing calamity and the inadvertent commitment of a faux pas, Brian keeps to himself, talking to co-workers only under duress. Avoiding improvisation and spur-of-the-moment decisions, Brian is keen on routines well-defined and predictable.

When we first meet Brian, he is about 30 years old, single, living in a small apartment, and already set in his ways. He loves films, however, and one night he decides to ride the local tram to the British Film Institute (BFI), which is showing a film he has long wanted to see. From enjoying that initial experience, Brian soon finds himself going to the BFI twice a week, and after six months or so, he decides to buy a membership in the BFI, to watch films more often. As his attendance increases, he notices a group of men—the same men every time—standing in the foyer discussing the film shown. Being Brian, he is too shy to approach the group, but loving films, he is curious about their conversation. He eventual allows himself to come within earshot of them and discovers a few enticing details: None are called by name, all have interesting things to say, and no one is trying to score points at the expensive of the others. The combined anonymity, camaraderie, and enthusiasm for film encourage Brian to approach the group and comment on a film. His comment is noted by the group and appreciated, and he soon finds himself joining in every night.

For a person so quiet and reserved, so frightened and anxious, Brian actually has a very rich inner life, thanks to the art of filmmaking and the camaraderie of kindred spirits. His taste in film is eclectic—the BFI screens films from around the world, from all decades and all genres—and he cultivates a specialized interest—post-War films from Japan—inspired to do so by the fact that each member of the group has a particular interest that allows the men to contribute comments from a variety of viewpoints. Thanks to a friendship he develops with one of the group members—ten years of after-film chatter leads to an invitation to tea—Brian develops a better-informed awareness of soundtracks and their composers. (John Zorn is mentioned and appreciated, and Brian even finds himself attending, by himself, a concert by Merzbow(!).)

Readers, too, discover a lot about films and filmmakers, about the joys and insights they bring to viewers’ lives, and how, by extension, the arts help people develop rewarding inner lives, even—and especially—for people like Brian. Perhaps the format of the novel Brian is author Jeremy Cooper’s own tip of the hat to Brian’s special appreciation of glacially paced Japanese films in which nothing much happens on the outside, but inside, the characters’ lives are tumultuous yet measured. By the novel’s end—40 years of Brian’s life have been covered—he finally works up the nerve to reciprocate an offered friendship. Anonymously, of course. So as not to draw attention to himself.

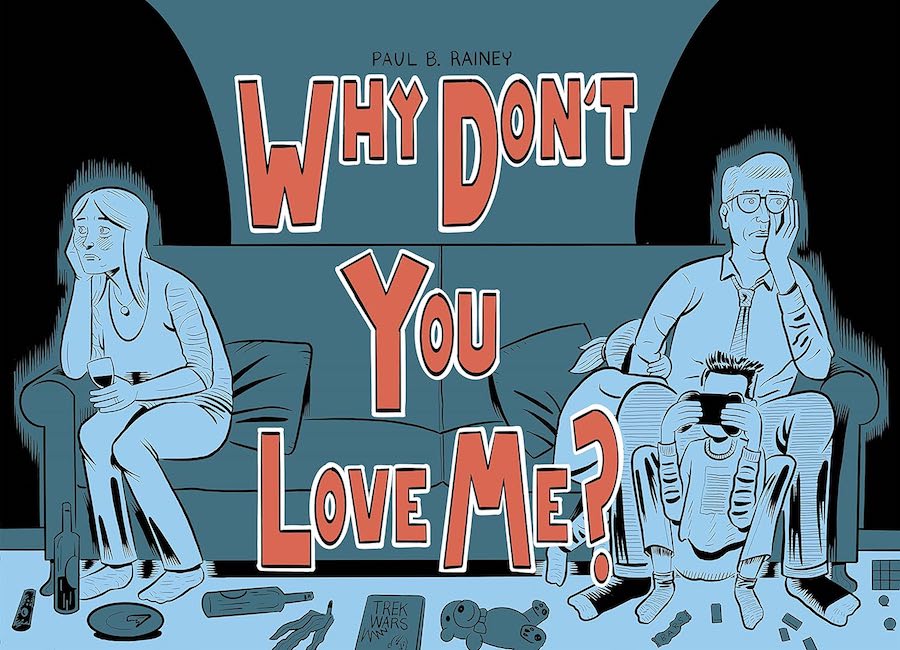

Why Don’t You Love Me?

Paul B. Rainey

Drawn & Quarterly

Why Don’t You Love Me? begins as a serial comic strip about a dysfunctional couple with two children. The father, Mark, can’t remember his children’s names or ages, and his wife, Claire, usually can’t remember her husband’s name. The children, Charley and Sally, have names that reference Charles Schulz’s Peanuts as does Mark’s training as a barber, although when the strip begins, he is on medical leave as website developer, a career he says he has no idea how to do.

Claire is an unemployed, chain-smoking, depressive alcoholic who passes her days on the couch dressed in her robe doing nothing. Charley and Sally are left on their own with little to no oversight, including whether they attend school, utterly neglected by both parents, neither of whom is willing to cook or do laundry. Mark spends his days at a computer—doing what is anybody’s guess—and Charley remains glued to his X-Box around the clock. And Sally? She’s around somewhere, making her presence known when she needs something.

If the black humor about a dysfunctional couple were all that this book were about—the zingers, lies, disappointments, and emotional manipulations—that would be fine in its cynical, nihilistic way. But Rainey takes Why Don’t You Love Me? past the tropes of Andy Capp minus the wife-beating to explore the nature of friendship, love, relationships, and commitments over time and place, using speculative fiction and facts about quantum physics to re-frame the context in which the domestic drama has been playing out its initial surface-level games illustrating the worst parts of the human condition.

Just as the extramarital peccadillos of Mark and Claire seem to be catching up to them, the narrative restarts—only this time, Mark is single, working competently as a barber, and Claire both lives with a man she likes (although he seems to barely tolerate her) and is gainfully (but unhappily) employed. Charley and Sally are gone, never even alluded to until the end. Is this a flashback to before the time Mark and Claire met? Or are we suddenly several years in the future and are waiting for Rainey to get around to explain what happened in between?

Neither, as it turns out. Why Don’t You Love Me? explores the possibilities of the “comic book” format in a way I haven’t felt since Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan came out and shows Rainey to be an ingenious writer of significant empathic depths.