I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: I arrogantly recommend…

The Apple in the Dark

The Apple in the Dark

Clarice Lispector/Benjamin Moser

New Directions

The plot outline of The Apple in the Dark is simple: A man commits a crime, goes into hiding in a remote, rural area, and takes a job as a menial laborer on a farm overseen by two women until things cool off. Trios lend themselves to conflict: in this case, the situation sparks underlying tensions of sex, dominance, and violence. Yet, what in other hands might make for the premise behind a noir novel, Clarice Lispector uses to explore metaphysical questions of being, of existence expressed in a coiling language in which concrete nouns torque into abstract conceptions pushing sense to the limits of coherence, much in the manner of, say, the Quentin section of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury or much of Light in August.

No one in life talks as Lispector’s characters do—they are ciphers she imbues with life to work out her own philosophical interests. Lispector the creator comes across as a person whose most satisfying experiences occur in her head, where she seems to have spent most of her time. Lispector’s characters, too, live in their heads, often trapped in thoughts they would rather not have yet are compelled to explore.

In The Apple in the Dark, Martim is a man on the run—from what isn’t at first clear. We know he’s committed a crime of passion, but neither the specific nature of the crime nor its result are stated. He is a man for whom a spontaneous act of rage initiates his freedom from cultural constraints: He no longer needs to act “intelligent,” has no need of speech, no need to fit in. Starting from zero, his re-birth will be based on actions taken, not in useless thoughts and conformity.

And what was keeping him going was the extraordinary impersonality that he’d reached, like a rat whose only individuality is whatever he inherited from other rats. That impersonality, the man kept it up by a slight repression of himself as if he knew that, as soon as he became himself, he would collapse capsized onto the ground. . .

His knowledge was slight, but his hands had earned a wisdom. “A man is slow and takes a long time to understand his hands,” he thought looking at them. His thoughts were almost voluntarily enigmatic. . . By not knowing, there was in the man a joy without a smile just as the plant fulfills itself, thick.

Apple acts as Lispector’s critique of both existentialism and what is now called toxic masculinity.

The farm that Martim comes across is run by a woman named Vitória who has taken in her cousin, Ermelinda, who has used, for the past three years she’s been living on the farm, her status as a former invalid to avoid work. The interior lives of Vitória and Ermelinda churn merely from Martim’s presence. Vitória is driven to a kind of rage because Martim accepts without grudge or argument her constant nagging to take up one set of repairs before another is finished. Those farming projects he does finish are “perfect” (her word), and she becomes angrier that he leaves her nothing to complain about. Her farm is becoming, in her word, “beautified.” Ermelinda falls in love with Martim for his stoicism, although her notions of love are expressed in a kind of twisted Faulknerian logic:

she was trying to recover in the field that minute in which she had daringly accepted loving the man: she was trying to recover the minute in order to destroy it. But, stunned, she might have known that the need to destroy love was also love itself because love is also a struggle against love, and if she realized it that’s because a person knows.

The Apple in the Dark represents Lispector at the height of her creative powers. It is with this intellectual and artistic triumph that New Directions ends its multi-year project to translate all Lispector’s works into English. Barry Moser should be commended for his success in conveying the richness of Lispector’s thought and prose.

Her Side of the Story

Her Side of the Story

Alba de Céspedes / Jill Foulston

Astra House

Her Side of the Story is a confession and meditation by a woman named Alessandra on what it is to love and be a woman in a rigidly conservative, patriarchal society. Consisting of three main parts (although the novel lacks divisions), the novel begins during the two world wars, from childhood to Alessandra’s teens, when she is close to her mother; to her late teens, when she lives with her grandmother and aunts; and, during WWII, to her early 20s as an independent, single woman, then as an independent, married woman.

Alessandra—Sandi—is the daughter of a would-be concert pianist, Eleanora, and a civil-servant father. Eleanora was forced to end her ambitions when she married to take up an unrewarding and unappreciated life as a mother. Alessandra’s father is a dull-minded, resentful man who treats his wife and daughter to dismissive sneers, refusing to seriously entertain their ambitions. To help make financial ends meet, Alessandra’s mother teaches piano to the girls of lower middle-class families, girls who will, in turn, become piano teachers themselves to daughters of lower middle-class families.

When a wealthy foreign family moves into the area, Eleanora is hired to provide the youngest daughter with musical training (she has no ear, talent, or interest) and eventually meets the girl’s older brother, Hervey, who has definite opinions about art, music, and literature, but doesn’t live often with the rest of the family. Eleanora falls in love. Rather than appalling her naïve daughter, the confidence and joy Sandi now sees in her mother elates her, gratified to see Eleanora—whom she adores—admired for her talents and interests. While Sandi’s father remains oblivious to his wife’s infatuation, Hervey encourages Eleanora to practice in earnest and give a concert at his parent’s estate.

Eleanora’s concert is a success, received with enthusiastic applause and a request for an encore, which enrages her husband. Three days later, Hervey confesses his love for Eleanora, and she makes plans to leave her husband, taking Sandi with her. On the cusp of womanhood, Sandi appreciates the hell her mother has had to endure, for she, too, has been on the receiving end of her father’s relentless debasing. Her father threatens to have the police stop Eleanora if she takes Sandi with her, and Sandi urges her mother to leave anyhow, which Eleanora does—by committing suicide. Her father then sends Sandi to live with his brother, her Uncle Rodolfo.

Upon entering Uncle Rodolfo’s household in Abruzzo, the south of Italy, Alessandra is met by several aunts and her Nonna, who rules its domestic affairs. Alessandra’s mother is never mentioned, let alone her suicide. The world of the household is rural, conservative, and deeply Catholic. In practice, this would usually mean an early marriage for Sandi (who is 17), followed by motherhood, and decades of domestic toil. Sandi is determined, however, to continue her studies, finish high school, then attend university. Nonna silently respects Sandi’s determination, while disagreeing with it, and her uncle gives her money with which to buy books.

In Abruzzo, people don’t smile and they do not tend to take joy in life—joy is something that happened a long time ago that life beat out of them. Sandi is introduced to a cousin, Giuliano, a boorish boy, hostile to Sandi’s habit of reading and sneers at her mother’s suicide and the fact that she had a lover. And so, she is introduced to another young man who also ignores her interest in educating herself, which he disapproves of but isn’t insistent upon—after all, he is in no position to make claims upon her. However, he does appreciate the fact that she is smart and pretty—two core ingredients in a potential wife, whose core qualities will also include abilities to breed and keep house. What’s not to like? For Alessandra, the man is handsome and about her age—a peer in an environment where peers are in short supply. But marriageable? Given her goals, not at all.

Her refusal to become engaged to him disappoints Nonna, who had hoped Sandi would give up her foolish notions to attend college and see the sense in marrying. Nonna at last relents to Sandi’s wish, assuming that ceding to this demand will slake Alessandra’s willfulness to spurn traditional womanhood. But Nonna comes to realize that Alessandra is not one to act on caprice, and dismisses her back to her father.

With her father again and beginning college, Alessandra meets a professor, Francesco, a man nine years her senior who is active in an underground anti-fascist movement during Mussolini’s tenure, starting with Italy’s wars in Africa and continuing throughout WWII, when Italy is part of Hitler’s Axis. Alessandra is charmed by his Francesco’s intelligence, wit, and dedication to a cause. (Until they meet, she is ignorant of politics.) He, too, is charmed by Alessandra’s intelligence and manners that transcend superficial silliness too common among uneducated women or women with only traditional, subservient lives for themselves in view.

They wed.

However much above the common fray they see themselves before the marriage—certain that theirs will not be the fate common to the majority of unhappy, unfulfilled couples surrounding them— Alessandra falls into a similar trap of misery. Franscesco remains willfully ignorant of her dissatisfaction. For his life is devoted to “the cause,” the greater good, which compels him to be absent from their apartment for longer and longer periods, until he is in hiding from the Italian police and military for his activities. Alessandra is eager to help the man she loves fight for the cause, too. But Francesco does not understand her offers as serious, responsible, committed acts—that is a realm for men.

Even after the war, he rebuffs her every offer to help, to play an active role in his life. While he will drop everything, spend all his time helping the cause, he will never drop everything to be with her. And so, Alessandra—the strong-willed woman who has always vowed since her teens to devote herself to love—must confront a painful truth about her commitment to Francesco. Her mother sacrificed her unhappy marriage for the love of a man who respected and encouraged her talents, only to kill herself; and she answered her Nonna’s question about a husband by saying she would live for love or kill herself. She now finds herself deep in love with a man who claims to love her, who doesn’t abuse her, who isn’t a philanderer. What solution does Alessandra have when her definition of love itself is the problem?

Unidentified man at left of photo

Unidentified man at left of photo

Jeff Bursey

corona/samizdat

Like Joyce’s Dubliners, Jeff Bursey’s Unidentified man at left of photo concerns moments in the lives of people from a single city. Like Lawrence Stern’s Tristam Shandy, Unidentified man questions through parody the conventions of how those lives are described. “If you want realism,” the narrator says at one point in the novel, “put your hand in a fire.”

Taking place in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island (PEI)—or pei in the novel’s lower-case diminishment of place names—and featuring—at first—a hapless character named Joe, the book begins with the discovery of a dead teenage girl rolled up in a carpet and dumped by the side of the road. The EMT, frustrated in his attempts to take the body to the morgue when the car in front of him doesn’t move once the light turns green, screams at the driver, “Is it a particular shade of green you’re waiting for?” Turns out, the driver of the car is dead, and we never hear about the dead girl again, or the other corpses that have been mysteriously turning up around town. Like Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon, there are certain places where decent people don’t dwell on such matters.

Instead of following a plot, Bursey’s narrator presents incidents and characters in terms of narrative conventions he intends to satisfy or deny: “A brother would be a useful creature for Joe to have, so he has four of them, and three sisters while we’re being so generous.” And “Angus MicMacMann, an uncle of Roger, who you’ll meet as soon as I invent him, sometimes wished there were more ethnic types in C-town, as then he could sell more flammable united statesian flags” [sic]. Unidentified man, then, is written as a number of improvised set pieces in which the narrator claims to be trying to adhere, more or less, to story-telling conventions, with varying degrees of success or interest in fulfilling. In fact, Joe is “here solely so you can have the assurance continuity of character presence brings,” while otherwise being ignored, for instance, during the exchange between a local shop owner of touristy ephemera and a local author who catalogs the wit and wisdom of the locals for tourist consumption.

About a local couple who seem to have an open relationship but who haven’t had their backgrounds explained to us so we can make sense of their choices, the narrator says,

You’ll insist on a back story so you can relate to them. That in itself is sad because, sweet Jesus, you know enough family and friends, and if you can’t relate to them but prefer entirely made-up ‘people’ who are only the products of a mind unfit for commerce, retail, pipe-fitting, working in the IT division of anywhere, owning a restaurant, or driving a cab, then you’re in a pretty sorry condition with respect to the world, and you ought to put this book down and call your parents or siblings or friends or go to the races or pay to get laid. Nothing I provide or withhold about these two mock-ups of ‘people’ is going to rescue from your own life.

And so it goes.

While Unidenified withholds plot, it does provide compelling characters, interesting incidents, and a story that simultaneously has the sort of verisimilitude that allows for suspension of disbelief, all while insisting on the arbitrariness and artificiality of the elements of prose that make for stories we want to care for and do. In achieving that, Bursey’s Unidentified man is like watching Penn & Teller perform a magic trick while telling us how it’s done, yet at the end we still find ourselves asking, “How did they do that?”

Interview with Jeff Bursey

No plot plus a narrator who thumbs his nose at conventional narrative tropes. You even include and “Endex” and photographs from places around Charlottetown, where the events occur, yet the narrative insists on hacking away at its own verisimilitude. How long did it take you to find a publisher for Unidentified man?

I tried Canadian publishers starting in late 2012 and a few others elsewhere but with no luck. In spring 2020 I started talking with Rick Harsch, head of corona\samizdat, about other things. One topic led to another, and Unidentified man at left of photo came out summer 2020. A typical leisurely journey for my fiction manuscripts. This one either fell into conservative hands or hands who didn’t know what to do with it or see how it rebelled, aesthetically (these days that’s almost the same as saying politically), against the current CanLit scene. (There are other rebels and we each have had a hard time getting mss accepted.) A scene dominated by dreary, allegedly realist and historical fiction. On the positive side, since it came out it’s found readers and fans all over the world.

Unidentified man is clearly—to me, at least—the work of a writer who enjoys storytelling but chafes at standard expectations. What do you see as the elements of an engaging narrative?

Placed as it is in the small capital city in the smallest province in Canada, the book is meant to show chafing on many levels, a friction that’s good for a work of art. It rubs against civic values, narrative staleness, and reader expectations, so thanks for using that exact word.

An engaging narrative can be many things. For me, increasingly, it’s good if it has some humour in it, and an awareness of the place of the book (if it’s new) in the here and now. I’ve read too many new novels from Canadians where you see writers simply repeating themselves in virtually the same style or tone as they did five or twenty years back, and then there are other writers who appear unaware, in the fiction they offer, of Modernism or Post-modernism. Novels and short-story collections that contain well-thought-out ideas and are ambitious in approach can be engaging. If the ideas are new or novel or original, then sometimes the style can take second place. Sometimes.

What qualities remain constant over time that make “the novel” a viable format?

The novel form is expandable and adaptable. People defined the novel, and every other art form, so we can change that definition whenever we want. The novel has room for authors who find crevices that haven’t been explored or are relatively unexplored in ways of speaking that are new. It’s healthy for literature to be resolute in looking ahead in terms of form/content and co-opting whatever is required of the manuscript being written.

Your narrator teases about provincial mores—small-mindedness, a preference to look the other way and not verbally confront impolite events. To what degree are your narrative choices an extension of that ribbing? Some of your characters—in particular Raymond and Terra, who have developed a deep friendship over the decades, even love, but remain married and sexually faithful to their spouses—reveal an inner life that their fellow C-towners, in their Evangelical protestant modesty, would be embarrassed to confess about themselves, should they be inclined to look inward.

The way people on PEI, not just in Charlottetown, complain or gossip about others is to do so privately and, if possible, anonymously. They used to be able to leave mean remarks at the bottom of news stories, for instance, under assumed names, which showed the falseness of their own notion that Islanders are, as they say of themselves, “nice.” Saying the same complaint aloud where you could be identified might mean you don’t get that job you wanted because the cousin of someone you vented about heard what you said and passed it on to a prospective employer. The narrative choices in this novel are meant to be discomforting and ugly, at times, and to mention real news stories, dressed up a bit here and there, and real people, so that complacency and smugness can be lanced. Similarly, the novel itself is a criticism of habits of thinking about what many people still think novels should be. Unidentified man at left of photo reminds readers, or tells them for the first time, what goes into writing and that authors can say anything, and that it’s all fiction. Of course, saying what you want means accepting the consequences, too, not only having fun.

Which authors and/or books have influenced your thoughts about writing, if not your writing itself?

Henry Miller, William Gaddis, Wyndham Lewis, Oulipians, John Dos Passos, Blaise Cendrars… many more. I’m constantly encouraged by the works of Lee Thompson, W.D. Clarke, S.D. Chrostowska, Tim Conley, Chris Eaton, and a few others, who have had to fight against the indifference and, sometimes, clear stupidity that prevents their works from being published by Canadian presses. It’s not accidental that corona\samizdat publishes some of those people. We owe Rick a great thanks for being hospitable to writing that’s contrary to the ideas the establishment of CanLit stands for.

What ideas or events do you find particularly motivate you to respond with a story?

Injustice and deep ineptitude, shallow responses to someone’s emotions, an amusement at whatever is considered the proper way things should be said or done. My first published book, Verbatim: A Novel, is about members of a fictional legislature in Canada. For years I listened to real politicians in the province I grew up in talk about a wide variety of matters and accumulated examples of their speech, foibles, and ideological mind-sets when speaking about things they were grossly under-qualified to address, in language that was painful to hear but amusing at the same time. A lot of anger built up and after finishing that book a fever slowly passed. My second novel, Mirrors on which dust has fallen, was about sex, religion, and art, and I got out some feelings and ideas that would be out of place in the first book.

What other stories do you have in the works or will be soon published?

Much as I’d like to talk about current projects, I can’t. The works will either come out, sooner or later, or not at all. Best to leave them aside so they can expand, or not, in peace.

Brian

Brian

Jeremy Cooper

Fitzcarraldo Editions

Brian tends to reticence and caution in personal and social interaction, an inborn temperament only exacerbated by his parents’ bullying and debasement, intended to toughen him up during his childhood in Northern Ireland. Free of their grip—his mother’s death when he is 16 and his estrangement from his father and older brother—he moves to England, becoming a file clerk for Kentish Town, a position he holds for the entirety of his professional career. Ever shy and awkward, always fearing calamity and the inadvertent commitment of a faux pas, Brian keeps to himself, talking to co-workers only under duress. Avoiding improvisation and spur-of-the-moment decisions, Brian is keen on routines well-defined and predictable.

When we first meet Brian, he is about 30 years old, single, living in a small apartment, and already set in his ways. He loves films, however, and one night he decides to ride the local tram to the British Film Institute (BFI), which is showing a film he has long wanted to see. From enjoying that initial experience, Brian soon finds himself going to the BFI twice a week, and after six months or so, he decides to buy a membership in the BFI, to watch films more often. As his attendance increases, he notices a group of men—the same men every time—standing in the foyer discussing the film shown. Being Brian, he is too shy to approach the group, but loving films, he is curious about their conversation. He eventual allows himself to come within earshot of them and discovers a few enticing details: None are called by name, all have interesting things to say, and no one is trying to score points at the expensive of the others. The combined anonymity, camaraderie, and enthusiasm for film encourage Brian to approach the group and comment on a film. His comment is noted by the group and appreciated, and he soon finds himself joining in every night.

For a person so quiet and reserved, so frightened and anxious, Brian actually has a very rich inner life, thanks to the art of filmmaking and the camaraderie of kindred spirits. His taste in film is eclectic—the BFI screens films from around the world, from all decades and all genres—and he cultivates a specialized interest—post-War films from Japan—inspired to do so by the fact that each member of the group has a particular interest that allows the men to contribute comments from a variety of viewpoints. Thanks to a friendship he develops with one of the group—ten years of after-film chatter leads to an invitation to tea—Brian develops a better-informed awareness of soundtracks and their composers. (John Zorn is mentioned and appreciated, and Brian even finds himself attending, by himself, a concert by Merzbow(!).

Readers, too, discover a lot about films and filmmakers, about the joys and insights they bring to viewers’ lives, and how, by extension, the arts help people develop rewarding inner lives, even—and especially—for people like Brian. Perhaps the format of the novel Brian is author Jeremy Cooper’s own tip of the hat to Brian’s special appreciation of glacially paced Japanese films in which nothing much happens on the outside, but inside, the characters’ lives are tumultuous yet measured. By the novel’s end—40 years of Brian’s life have been covered—he finally works up the nerve to reciprocate an offered friendship. Anonymously, of course. So as not to draw attention to himself.

The Logos

The Logos

Mark de Silva

Clash Books

The Logos is a Faustian tale about an artist—the unnamed narrator—midway through life’s gloomy wood whose girlfriend of two and a half years, Claire, leaves him shortly after he decides to quit the world of gallery shows and the rigamarole that accompanies it. But he has bills to pay and has sold the last of his pictures (of Claire) to an avid (and wealthy) collector, so is at sea with what to do next. In this rich and learned novel of ideas, the narrator is well-read and (in many ways) self-educated (beyond the minimum requirements of his otherwise solid undergraduate years), whose opinions—on art, communications, sensory experience, film, sports, and more—are richly detailed, nuanced, and well-reasoned. Almost every paragraph of this novel is a mini-essay on whatever topic comes to his mind, articulate and graceful.

The narrator and his circle of friends come from money, going back three generations for the nouveau-est of the riche and eight generations for those who satisfy the American version of old money. They have been steeped in high culture all their lives, take it seriously, and have used the advantages of their families’ wealth to further cultivate and explore their interests. One faction of his peers have been publishing a high-end arts journal, Cosquer (significant production values, no advertising), for which the narrator has served in an editorial capacity as well as contributing pictures of his own for publication, but has been steadily withdrawing from along with everything else. Cosquer has suffered financial problems and has begun considering what had once been unthinkable: Accepting advertising.

Enter James Garrett, owner of several companies involved in materials science and engineering, also from wealth and himself presumably worth billions, although a dollar amount is never given. He has several products in development for which he would like to develop a stealth ad campaign for: a whiskey, a sports drink (along the lines of Gatorade but with a kick), and sunglasses. Turns out he’s a fan of the narrator’s work, finds it rich in emotional and philosophical implications, and would like the narrator to develop a series of images that would suggest qualities associated with the products and two unknown people up-and-coming in the worlds of sport and theater. Karen, the head of Cosquer and a friend of the narrator’s from college, will provide the copy. Will the narrator, the pure artist, succumb to working in the realm of crass commercialism—although of the refined sort for the well-heeled (the Cosquer set), where art and commerce often intermingle, comment upon, and influence each other, though for different ends?

Well, not in that way, no. The narrator will not agree to typography appearing on or seeming to comment upon the pictures he creates. Garrett agrees, and the narrator is given carte blanche to buy whatever materials he needs, spend whatever is needed to meet and get to know the two human principles—Duke, the football player, and Daphne, the actor—and so forth, while Cosquer will receive generous funding to keep it afloat. The narrator soon sets to work:

In a single weekend I’d gathered proof of the adequacy of materials: Daphne and Duke. Which meant that when this bleariness abated [the hangover from his time with Duke], there’d be real work to be done, not mere trial runs, or just final pieces to previous puzzles, like those morose portraits of Claire that had come to dominate my life. It had been a year at least since I’d last worked with this excitement of possibility, of opening rather than closing vistas. Along with this would be the first serious money in a while, quite possibly more of it than I’d yet experienced or had any right to expect had I carried on with Sandy and his vaunted gallery. With philanthropists like Garrett, you really couldn’t know just how lucky you were going to be.

Indeed.

And about three-quarters through the book, the narrator realizes that, in his deal with Garrett, he has traded his freedom for joys.

The drinks, especially Theria the sports drink, alter the narrator’s perceptions, as do the sunglasses. Already hyper-articulate and keenly insightful about how art conveys to viewers its effects and understanding of the subject, and already possessed of better than 20-20 vision, these performance-enhancing materials further heighten his awareness and sensory stimulation. Theria itself seems to induce withdrawal effects, and the narrator is reluctant to drink more when Garrett tells him that the formula for it hasn’t yet received FDA approval. Additional joys come in the form of the emotionally and physically fraught relationships he develops with Daphne and Duke. Furthermore, it turns out that Garrett’s other companies, those responsible for most of his wealth beyond that inherited from his parents, are devoted to toxic waste and crowd-control munitions.

By the novel’s end, many of these issues have been worked out but those that remain seem to contradict the direction indicated by the narrative: Although the narrator is inclined to take seriously Garrett’s underlying notions of godliness and doing right, neither Garrett nor the narrator question the fact that Garrett’s “solutions” to the problems of toxic waste and riot control are to capitalize on them rather than address the systemic conditions that give rise to them. And for all the narrator’s focus on his choice of materials for his pictures—graphite, pastels, paper characteristics and qualities—those considerations don’t arise once his pictures start to appear on the sides of cabs, on billboards, and on skyscrapers, as if his underlying notions of successful artistic expression reduced to ubiquity and scale.w

These issues aside, The Logos is one of the finest novels I’ve read in the past couple of years, along the lines of Jim Gauer’s Novel Explosives in its willingness—its insistence—on exploring motivations and choices regarding significant ethical issues. And while I was surprised at and disappointed by the end of The Logos, at least Mark de Silva—like Dostoevsky and Philip Roth—has given us characters worth arguing with.

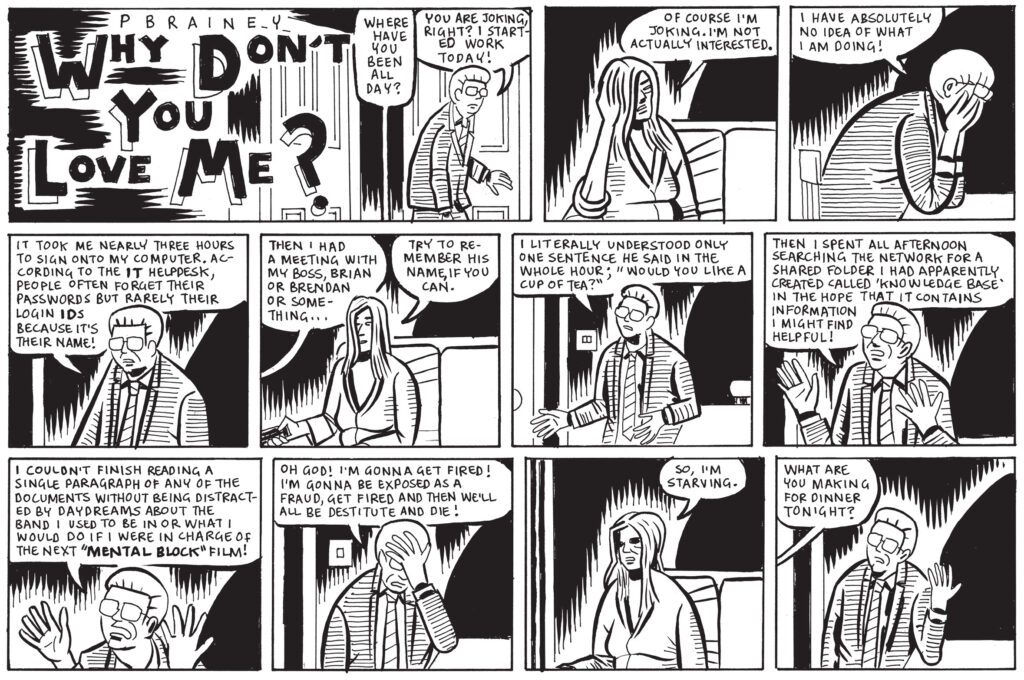

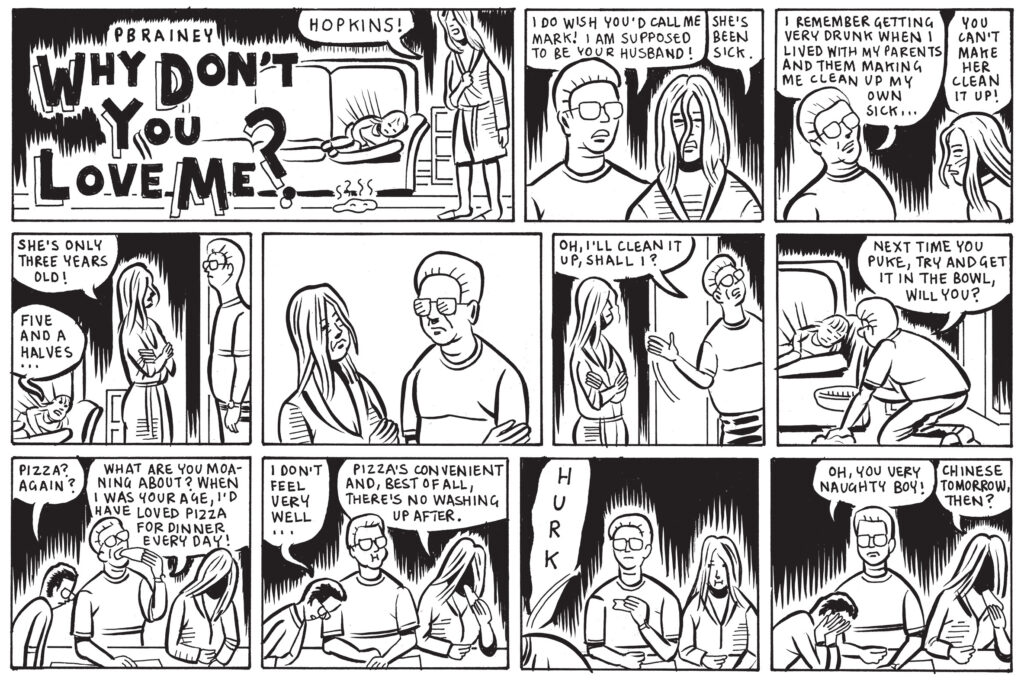

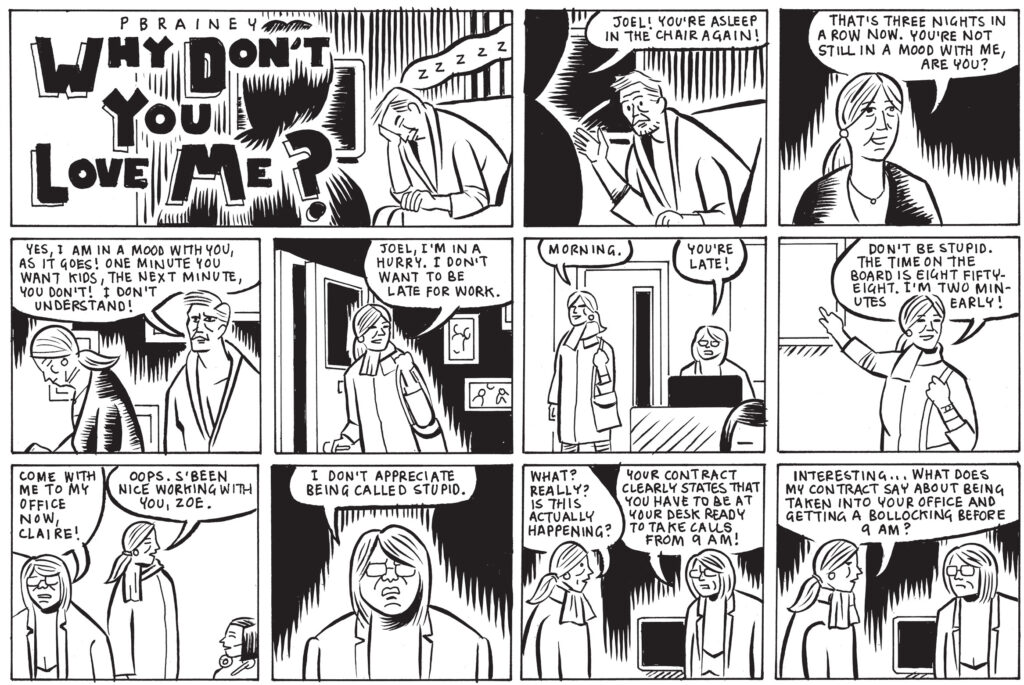

Why Don’t You Love Me?

Why Don’t You Love Me?

Paul B. Rainey

Drawn & Quarterly

Why Don’t You Love Me? is a British comic strip about a dysfunctional couple with two children. The father, Mark, can’t remember his children’s names or ages, and his wife, Claire, usually can’t remember his name. The children, Charley and Sally, have names that reference Peanuts as does Mark’s training as a barber, although he currently is on medical leave as website developer, a career he often says he has no idea how to do.

Claire is an unemployed, chain-smoking, depressive alcoholic who spends most of her days dressed in her robe sitting on the couch doing nothing. Charley and Sally are left on their own with little to no oversight, utterly neglected by both parents, neither of whom is willing to cook and neither of whom know what day it is and whether the kids should be in school. Mark spends his days at a computer—doing what is anybody’s guess—and Charley remains glued to his X-Box around the clock. In other words, Why Don’t You Love Me? has all the ingredients of pure comedy gold.

Parental neglect, self-absorption, and lies form the fabric of the family dynamics, and mom and dad’s days of intimacy ended long ago, each sleeping in separate rooms: Mom in the bedroom, dad on the living room couch—unless Claire has passed out drunk there, in which case, Mark kicks Charley out of his bedroom to sleep on the couch with Claire. And Sally? She’s around somewhere, making her presence known when necessary.

Here’s some dialogue from the opening two strips:

Charley: Mummy! Mummy! Can we go to school today?

Claire: Jesus. . . Why are you asking me for? How should I know?

Mark: Thomas. . . Tommy. . . Tom. . . Whatever your name is. . . Go and put your uniform on. I’ll take you.

Sally: Where is our uniforms?

Mark: I don’t know. Wherever you left it. Scattered across your bedroom floor?

Sally: But it’s dirty!

Mark: Look, do you want to go to school or don’t you? [To Claire, who’s just lit a cigarette:] Um. . . Do you think you should be doing that indoors? You know. . . Passive smoking and all that?

Claire: Christ! You mean this all might be real? [Stubs out cigarette.] There! Happy now?

Claire: [To Charley:] Who the hell is this kid?

Charley: It’s my friend, Mum. Remember?

Claire: Thank God! For a moment, I thought there was another one! [To Mark sitting at the computer:] Still pretending you can’t remember the password eh?

Mark: How many times do I have to tell you? F’god’s sake!

Claire: What about the kids’ names?

Mark: Good idea. [Types.] T. . . O. . .

Claire: Charley! His name is Charley!

Mark: Right, right, of course. Does that end E. . . Y. . . or I. . . E. . . ? No matter, I’ll try both. Nope. Nope. I’ll try “Charles.” Nope. S. . . A. . . double L. . . Y. . . Nope. What’s “Sally” short for?

Claire: It’s not short for anything, you idiot! It’s just “Sally”!

If the black humor about a dysfunctional couple were all that this book were about—the zingers, the lies, disappointments, and emotional manipulations—that would all be fine in its cynical, nihilistic way. But Rainey is doing something else here that takes Why Don’t You Love Me? past what it seems to be—a daily or weekly comic strip about domestic life a la “Andy Capp” minus the wife-beating—and reveals Rainey merely to be using the tropes of comic strips as a red herring. Instead, he explores other possibilities latent within the graphic narrative format that make it far more interesting than conventional strips in what it has to say about friendship, love, relationships, and commitments over time and place, using speculative fiction and facts about quantum physics to frame aspects of the human condition.

Just as the extramarital peccadillos of Mark and Claire seem to be catching up to them, the narrative seems to start over again—only this time, Mark is working as a barber and Claire lives with another man she likes (although he seems to barely tolerate her) and is gainfully employed, to boot. Charley and Sally are nowhere to be seen and are not even alluded to. Is this a flashback to before the time Mark and Claire met? Or are we suddenly several years in the future and are waiting for Rainey to get around to explain what happened in between?

Neither, as it turns out. Why Don’t You Love Me? explores the possibilities of the “comic book” format in a way I haven’t felt since Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan came out, and shows Rainey to be an ingenious writer of significant empathic depths.

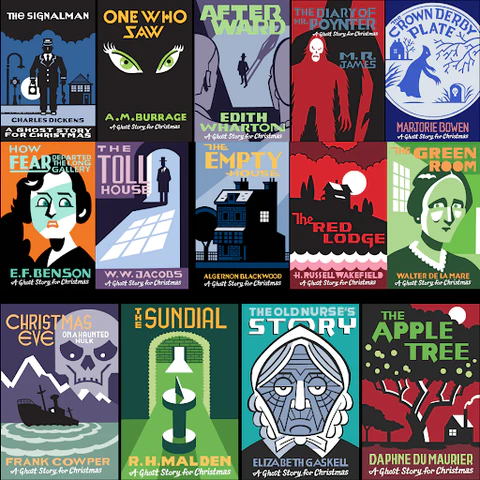

Seth’s Christmas Ghost Stories

Seth (illus.)

Biblioasis

Seth—illustrator, graphic novelist, and decorator (his term)—returns for another season of ghost stories for Christmas, single-handedly reviving an otherwise defunct holiday tradition among Northern Hemisphere English-speaking countries of combining eerie tales with the Yuletide (even though the tales have nothing to do with Christmas)—now with Seth’s moody black and white decorations to help the uncanny mood along.

Captain of the Polestar by Arthur Conan Doyle. Arthur Conan Doyle’s captain is an Ahab-like figure (although it’s unlikely Doyle was familiar with Moby-Dick) whose ship, the Pole-Star, a whaler, has been iced in an ice floe long enough for food rations and morale to run low while waiting for a path to open up to pursue of pod of whales he had seen before the ship became sealed in. Further eroding the crew’s morale is an eerie, keening voice heard at night, along with the wispy figure of a woman in the distance. Captain Craigie is set on waiting until the floe melts to pursue the whales; the crew is set on leaving because they are terrified by the haunting and can find more regular, if less lucrative, fishing jobs back home.

Captain of the Polestar by Arthur Conan Doyle. Arthur Conan Doyle’s captain is an Ahab-like figure (although it’s unlikely Doyle was familiar with Moby-Dick) whose ship, the Pole-Star, a whaler, has been iced in an ice floe long enough for food rations and morale to run low while waiting for a path to open up to pursue of pod of whales he had seen before the ship became sealed in. Further eroding the crew’s morale is an eerie, keening voice heard at night, along with the wispy figure of a woman in the distance. Captain Craigie is set on waiting until the floe melts to pursue the whales; the crew is set on leaving because they are terrified by the haunting and can find more regular, if less lucrative, fishing jobs back home.

The story is told as a set of diary entries by a doctor friend of the captain who is along for the ride and companionship of the captain. The friend acts as a mediating force between the captain and his crew, and represents the one person on board possessed of a rational mind, unaffected by unrealistic obsessions, such as the captain’s, or irrational beliefs in ghosts, such as the crew’s. The veracity of his narrative serves to lead skeptical readers into suspending their disbelief to enter into the mystery behind the mad creepiness enveloping the expedition.

The House by the Poppy Field by Marjorie Bowen. This moody set piece is a study in disquiet, in which an aging by not terribly old man returns to a manor that has been in the family for generations but has been allowed to slowly deteriorate by paying a real-estate manager to do the bare minimum for estate care but enough to pay for repairs and grounds maintenance. Strolling around the grounds, John Maitland, the scion of the estate, discovers a grave on unconsecrated ground, far separated from the church and the cemetery where the townspeople are buried. The tombstone bears the name of another John Maitland who died a century earlier under unwholesome circumstances—soon after conjuring from the dead another family member from even further back in time, one Joan Maitland, who was 19 years old when she died. The current John Maitland finds himself completing an unholy alliance of blasphemers.

The House by the Poppy Field by Marjorie Bowen. This moody set piece is a study in disquiet, in which an aging by not terribly old man returns to a manor that has been in the family for generations but has been allowed to slowly deteriorate by paying a real-estate manager to do the bare minimum for estate care but enough to pay for repairs and grounds maintenance. Strolling around the grounds, John Maitland, the scion of the estate, discovers a grave on unconsecrated ground, far separated from the church and the cemetery where the townspeople are buried. The tombstone bears the name of another John Maitland who died a century earlier under unwholesome circumstances—soon after conjuring from the dead another family member from even further back in time, one Joan Maitland, who was 19 years old when she died. The current John Maitland finds himself completing an unholy alliance of blasphemers.

A Room in a Rectory by Andrew Caldecott. A mid-20th-century ghost story with hints of Victorian-era tales: A young pastor, Nigel Tylethorpe, is given his own parish in an old country village, inheriting a large manor on a large estate with a questionable past and a peculiar haunting limited to pastors who write their sermons in one particular room of the manor, now locked and unused and avoided by the servants. As is common with these ghost stories, a battle ensues both between the forces of good and evil and between rational and irrational thinking, with the irrational serving as the underlying foundation of the world—one created by God but inhabited by evil spirits waiting to undo that creation and its notions of goodness. The questions for reader are, will Rev. Tylethorpe solve the mystery of the rectory—and under what terms?

A Room in a Rectory by Andrew Caldecott. A mid-20th-century ghost story with hints of Victorian-era tales: A young pastor, Nigel Tylethorpe, is given his own parish in an old country village, inheriting a large manor on a large estate with a questionable past and a peculiar haunting limited to pastors who write their sermons in one particular room of the manor, now locked and unused and avoided by the servants. As is common with these ghost stories, a battle ensues both between the forces of good and evil and between rational and irrational thinking, with the irrational serving as the underlying foundation of the world—one created by God but inhabited by evil spirits waiting to undo that creation and its notions of goodness. The questions for reader are, will Rev. Tylethorpe solve the mystery of the rectory—and under what terms?

“During the Victorian era many magazines printed ghost stories specifically for the Christmas season. These ‘winter tales’ didn’t necessarily explore Christmas themes. Rather, they were offered as an eerie pleasure to be enjoyed on Christmas Eve with the family, adding a supernatural shiver to the seasonal chill”.

–A Biblioasis introduction found in each copy of Seth’s ghost stories

Iyagi Chapbook Series

Strangers Press

Strangers Press is in Norwich, England. Its Iyagi Chapbook series is the latest group of chapbooks that present groups of eight short stories—available individually or as complete sets—by authors from around the world, including Lithuania, Switzerland, Netherlands, and Japan

Knock Off Viagra and Jeje by Sang Young Park (Anton Hur, trans.). Jeje is the quasi-boyfriend of the anonymous narrator, both men in their 30s from wealthy families, although Jeje has depleted his savings on frivolous affairs and a taste for expensive clothing and knickknacks. Jeje works now as an expensive prostitute, often servicing wealthy men who lead heterosexual lives with wives and families. But one of Jeje’s joys in life is different sex every day in different hotels. Both he and the narrator are fairly indifferent to wearing condoms, depending on whether they like the men they’re with. The narrator is unhappy with Jeje profligate life, less so about his promiscuity because the narrator too is promiscuous but he just does it for the quick hook-up—he would seem to be happier if the Jeje were more devoted to him than his johns, although it’s unlikely that such an arrangement would reduce by much the promiscuity they both engage in. The narrator doesn’t seem to enjoy his hook-ups as much as Jeje. He does want more of an emotional attachment. The only reciprocal emotional attachment he’s had was with a man identified only as Q, who eventually killed himself. Knock Off Viagra and Jeje reflects the disdain with which much of conservative Korea views homosexuality and the unsatisfying, dissolute lives many homosexual men engage in as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Knock Off Viagra and Jeje by Sang Young Park (Anton Hur, trans.). Jeje is the quasi-boyfriend of the anonymous narrator, both men in their 30s from wealthy families, although Jeje has depleted his savings on frivolous affairs and a taste for expensive clothing and knickknacks. Jeje works now as an expensive prostitute, often servicing wealthy men who lead heterosexual lives with wives and families. But one of Jeje’s joys in life is different sex every day in different hotels. Both he and the narrator are fairly indifferent to wearing condoms, depending on whether they like the men they’re with. The narrator is unhappy with Jeje profligate life, less so about his promiscuity because the narrator too is promiscuous but he just does it for the quick hook-up—he would seem to be happier if the Jeje were more devoted to him than his johns, although it’s unlikely that such an arrangement would reduce by much the promiscuity they both engage in. The narrator doesn’t seem to enjoy his hook-ups as much as Jeje. He does want more of an emotional attachment. The only reciprocal emotional attachment he’s had was with a man identified only as Q, who eventually killed himself. Knock Off Viagra and Jeje reflects the disdain with which much of conservative Korea views homosexuality and the unsatisfying, dissolute lives many homosexual men engage in as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

For That Which Cannot Be Restored by Park Wannsee (Soobin Kim, trans.). In 1950, when Korea was in the midst of a civil war that would ultimately divide the country into North and South Korea, communists were finally expelled from Seoul. Civilians who had shown leftist tendencies were either abducted by northern forces or were exiled there. Others were arrested by southern forces, some of whom were executed. Both fates affected for generations the family members who stayed behind or were later born into the family. It was one thing to be abducted—an act not necessarily voluntary—and another to be arrested and executed, which suggested an intolerable level of collaboration with the enemy. In either case, many South Korean families found the situation to be embarrassing, better to not be talked about, better yet to be forgotten.

For That Which Cannot Be Restored by Park Wannsee (Soobin Kim, trans.). In 1950, when Korea was in the midst of a civil war that would ultimately divide the country into North and South Korea, communists were finally expelled from Seoul. Civilians who had shown leftist tendencies were either abducted by northern forces or were exiled there. Others were arrested by southern forces, some of whom were executed. Both fates affected for generations the family members who stayed behind or were later born into the family. It was one thing to be abducted—an act not necessarily voluntary—and another to be arrested and executed, which suggested an intolerable level of collaboration with the enemy. In either case, many South Korean families found the situation to be embarrassing, better to not be talked about, better yet to be forgotten.

For That Which Cannot Be Restored deals with a manuscript submitted to a literary journal published by the South Korean government for a writing competition. Government-run literary journals are held in suspicion by literary writers (as opposed to writers of generic entertainments) for their didactic, pro-South Korean slant. XXX, a literary writer, has been hired to serve as judge in the writing competition, although he has reservations about the assignment, given the disdain with which the journal is held by his peers. With a thaw in what the government will allow to be published by writers who were abducted or exiled to the north, he has been asked to write the forward to an anthology of stories by a writer named Song who was actually executed by southerners not abducted—an embarrassment to the South Koreans and Song’s descendants who are reluctant to confront their nation’s past.

The Greatest Gamble on Earth by Kwak Jaesik (Hyonwon Yun, trans.). The value of friendship, contentment, and doing right by those whose companionship has emotionally enriched your life, though in ways not easily articulated, is the theme of Kwak Jaesik’s story about two women who meet in college and only sporadically keep up via email over the years. The narrator is a driven student, set on graduate school early in her college years, aiming to study a promising new field in neurobiology. Her friend, Han Seungun-hui, comes from a wealthy family, well-established over the past four generations through a company called Alpha Industries, now led by Seunghun-hui’s mother. Unlike most Koreans anxious to get into college, Seungun-hui is confident in her abilities to succeed on her exams and easily enter both college and grad school, with a focus on dinosaurs. Through her family’s money, she is able in high school to fund and participate in dinosaur digs and make honest claims to discoveries many tenured faculty would be jealous of. For the narrator, things turn out differently as the promising field she had devoted thousands of hours and many years of her life to has fizzled out, with few companies interested in hiring people with her skills. But one day, many years after college and the last time they saw each other in person, Seungun-hui writes the narrator asking if they can meet. Seungun-hui’s mother has been charged with financial improprieties by members of the judiciary in the pay of Alpha Industry’s rivals, eager to dismantle her company and personal fortunes. What role can the narrator possibly fill to help her old friend Seungun-hui, who is also now struggling with her own career?

The Greatest Gamble on Earth by Kwak Jaesik (Hyonwon Yun, trans.). The value of friendship, contentment, and doing right by those whose companionship has emotionally enriched your life, though in ways not easily articulated, is the theme of Kwak Jaesik’s story about two women who meet in college and only sporadically keep up via email over the years. The narrator is a driven student, set on graduate school early in her college years, aiming to study a promising new field in neurobiology. Her friend, Han Seungun-hui, comes from a wealthy family, well-established over the past four generations through a company called Alpha Industries, now led by Seunghun-hui’s mother. Unlike most Koreans anxious to get into college, Seungun-hui is confident in her abilities to succeed on her exams and easily enter both college and grad school, with a focus on dinosaurs. Through her family’s money, she is able in high school to fund and participate in dinosaur digs and make honest claims to discoveries many tenured faculty would be jealous of. For the narrator, things turn out differently as the promising field she had devoted thousands of hours and many years of her life to has fizzled out, with few companies interested in hiring people with her skills. But one day, many years after college and the last time they saw each other in person, Seungun-hui writes the narrator asking if they can meet. Seungun-hui’s mother has been charged with financial improprieties by members of the judiciary in the pay of Alpha Industry’s rivals, eager to dismantle her company and personal fortunes. What role can the narrator possibly fill to help her old friend Seungun-hui, who is also now struggling with her own career?

Like a Barbie by Park Min-Jun (Claire Richards, trans.). Yumi is at an impasse: Her dissertation committee is disappointed in and unimpressed by the document she has submitted as a philosophical disquisition on the “new literacy” required by social media. Stalling over the required changes and hedging as the deadline approaches, she whiles away her time in the graduate student library, quietly stalked by a Chinese graduate student who seems to do nothing else but surf the internet. He never talks to Yumi, however, or attempts to touch her, so she feels that she can’t protest over a man who merely sits near wherever she chooses to sit. He is easily ignorable if a bit creepy.

Like a Barbie by Park Min-Jun (Claire Richards, trans.). Yumi is at an impasse: Her dissertation committee is disappointed in and unimpressed by the document she has submitted as a philosophical disquisition on the “new literacy” required by social media. Stalling over the required changes and hedging as the deadline approaches, she whiles away her time in the graduate student library, quietly stalked by a Chinese graduate student who seems to do nothing else but surf the internet. He never talks to Yumi, however, or attempts to touch her, so she feels that she can’t protest over a man who merely sits near wherever she chooses to sit. He is easily ignorable if a bit creepy.

While mulling over her dissertation committee’s complaints and half-heartedly researching books and articles relevant to the required changes, she reflects on the fate of her older cousin, simply referred to as “oppa,” a deeply nerdy boy five years her elder who spent much of their youth together buying comic books and toy robots. While in elementary and middle school, Yumi spends her time in his room studying for class and occasionally reading his comic books while oppa spends hours on his computers. A disappointment to his hostile father, oppa is routinely bullied at school and seems unable to pass the simplest exam. However, it turns out that his time on the internet has been spent studying robotics programming, and he wins a scholarship to an elite university.

The insight Yumi needs to complete her dissertation is wrapped in the fate of her cousin and the reason the Chinese student has been stalking her.

Walk with a Goddess by Ji-Min Lee (Paige Ariyah Morris, trans.), Iyagi Chapbook Series, Strangers Press. Yeoshin has an unusual past that has prompted a casual acquaintance to call her after the two had last seen each other several years back. The man had been a friend of one of her former boyfriends, and they had only met a couple of times. Yet, the man tells her, it is of utmost importance that he talks to her. Interviews her, actually, to confirm rumors he’s heard about her over the past few years. “Yeoshin” means “goddess,” but in the case of this story’s Yeoshin it has been so only in the sense of misfortune—specifically, misfortune for several of the boyfriends in her life, each of them who had a parent who died while they were with her. Apparently, it is considered very bad luck to be away from a parent when they die, not to hear their last words, not to worry over them as they had worried over their sons when they were still in the womb. It has given Yeoshin an odd aura, adding a layer of melancholy to her life for this relentless and awful streak. But could her misfortune be her acquaintance’s good luck—and theirs?

Walk with a Goddess by Ji-Min Lee (Paige Ariyah Morris, trans.), Iyagi Chapbook Series, Strangers Press. Yeoshin has an unusual past that has prompted a casual acquaintance to call her after the two had last seen each other several years back. The man had been a friend of one of her former boyfriends, and they had only met a couple of times. Yet, the man tells her, it is of utmost importance that he talks to her. Interviews her, actually, to confirm rumors he’s heard about her over the past few years. “Yeoshin” means “goddess,” but in the case of this story’s Yeoshin it has been so only in the sense of misfortune—specifically, misfortune for several of the boyfriends in her life, each of them who had a parent who died while they were with her. Apparently, it is considered very bad luck to be away from a parent when they die, not to hear their last words, not to worry over them as they had worried over their sons when they were still in the womb. It has given Yeoshin an odd aura, adding a layer of melancholy to her life for this relentless and awful streak. But could her misfortune be her acquaintance’s good luck—and theirs?

Towards 0% by Seo Ije (Rachel Min Park, trans.), Iyagi Chapbook Series, Strangers Press. Despite the popularity of film in Korea, with over 200 million people watching films annually, the market is limited to a small handful of movies made by successful directors. Any film by any director that fails to reach at least 10 million viewers will mark the end of that director’s career because the money for filmmaking is held by a few conglomerates that hunger for profits. Thus, to receive money from a conglomerate to make a film means the director is at the beck and call of those producers. All independence is gone. Yet thousands of filmmakers and would-be filmmakers are drawn to movies as a way to express their independent visions. Independent films tend to be made on an almost voluntary basis—they certainly have very small budgets, if any—and tend to be made only during the director’s spare time from their day jobs. Worse yet, few people attend these films (attendance of fewer than 10 souls is common) and access to the popular chain theaters nearly impossible. Not surprisingly, then, many directors and would-be directors wonder if the excruciating process is worth it. And that’s the dilemma facing the narrator of Towards 0%.

Towards 0% by Seo Ije (Rachel Min Park, trans.), Iyagi Chapbook Series, Strangers Press. Despite the popularity of film in Korea, with over 200 million people watching films annually, the market is limited to a small handful of movies made by successful directors. Any film by any director that fails to reach at least 10 million viewers will mark the end of that director’s career because the money for filmmaking is held by a few conglomerates that hunger for profits. Thus, to receive money from a conglomerate to make a film means the director is at the beck and call of those producers. All independence is gone. Yet thousands of filmmakers and would-be filmmakers are drawn to movies as a way to express their independent visions. Independent films tend to be made on an almost voluntary basis—they certainly have very small budgets, if any—and tend to be made only during the director’s spare time from their day jobs. Worse yet, few people attend these films (attendance of fewer than 10 souls is common) and access to the popular chain theaters nearly impossible. Not surprisingly, then, many directors and would-be directors wonder if the excruciating process is worth it. And that’s the dilemma facing the narrator of Towards 0%.

Take My Voice by Serang Chung (Anton Hur, trans.). An allegorical tale of modern South Korea in which a prison has been built for citizens with unique but unfortunate talents. Yeo Seunggyun is a 34-year-old teacher of English who is arrested one day because his former pupils have each committed a series of murders. Seunggyun lectures aren’t full of hatred, they lack instructions to commit evil deeds but, the warden explains to him, something in the quality of his voice triggers people to do horrific things after hearing him every day for at least six months. Another inmate is a vector for bad diseases that never harm him himself, another, a young woman, is compelled to eat corpses. Oddly enough, none of inmates have an effect on the others. Seunggyun finds out he is being sentence for life because of his voice—unless he agrees to an operation that will remove his voice box.

Take My Voice by Serang Chung (Anton Hur, trans.). An allegorical tale of modern South Korea in which a prison has been built for citizens with unique but unfortunate talents. Yeo Seunggyun is a 34-year-old teacher of English who is arrested one day because his former pupils have each committed a series of murders. Seunggyun lectures aren’t full of hatred, they lack instructions to commit evil deeds but, the warden explains to him, something in the quality of his voice triggers people to do horrific things after hearing him every day for at least six months. Another inmate is a vector for bad diseases that never harm him himself, another, a young woman, is compelled to eat corpses. Oddly enough, none of inmates have an effect on the others. Seunggyun finds out he is being sentence for life because of his voice—unless he agrees to an operation that will remove his voice box.

Staying in prison isn’t without its rewards, however. The inmates get along with each other, have their own rooms, are served good food, and are able to order items they enjoy to pass the more enjoyably—karaoke machines, films, books, and so forth. At least the judicial system recognizes that everyone in the prison lacks evil intent and that most of them had no idea of their effect on others until they were arrested. Each inmate quickly comes terms with their arrest, even though they are forbidden contact with anyone outside the prison. They don’t even know where the prison is.

Then one day a young woman named Shin Yeonsun is admitted to the prison, accused of driving those around her to take up various addictions or obsessions. Unlike the others, she initially protests violently against being held for vague, unproveable charges before resigning herself to living there and befriending the other inmates, who find her kind and charming. When Yeonsun suddenly becomes ill from one disease after another, they realize that unless she can escape from the prison she will die. Her plight is the spark that changes the lives of those around her, if they are willing to break their chains of normality.

Kyoko and Kyoje by Han Jyunghun (Emily Yae Won, trans.). On May 18, 1980, South Korean troops shot, killed, raped, and beat up to 2,300 students who had been protesting against the installation of dictator Chun Doo-hwan after the assassination the previous October of the authoritarian president Park Chung-hee. Tired of the military and authoritarian dictatorships that had ruled South Korea for decades, students at Chonnam National University in the city of Gwangju—and other universities around South Korea—protested for democratic reforms after Park’s assassination. The massacre ordered by Chun is still denied or ignored by right-wing political forces, but in 1997 May 18 was made a National Day of Commemoration for those students harmed by the government.

Kyoko and Kyoje by Han Jyunghun (Emily Yae Won, trans.). On May 18, 1980, South Korean troops shot, killed, raped, and beat up to 2,300 students who had been protesting against the installation of dictator Chun Doo-hwan after the assassination the previous October of the authoritarian president Park Chung-hee. Tired of the military and authoritarian dictatorships that had ruled South Korea for decades, students at Chonnam National University in the city of Gwangju—and other universities around South Korea—protested for democratic reforms after Park’s assassination. The massacre ordered by Chun is still denied or ignored by right-wing political forces, but in 1997 May 18 was made a National Day of Commemoration for those students harmed by the government.

The event is probably unknown or has been forgotten by most Americans (I was a senior in college when it happened), but it increasingly informs the background to Kyoko and Kyoje as the story goes on, a background Koreans won’t need explained to them but American readers will need glossed to appreciate the strong emotional and moral issues underpinning the story.

Kyoko and Kyoje begins as a recollection of a group of four friends in middle school, three girls and a boy. The boy acts effeminately, for which he is routinely teased and beaten in school, and, after puberty kicks in, he shows one of the girls in the group that he also menstruates. A hermaphrodite who identifies most strongly with their female side, eventually taking to wearing women’s clothes and presenting as female once in college. Illustrating the adage that “the personal is political,” author Han Jyunghun (whose prose is deftly translated into English by Emily Yae Won) slowly moves the narrative of one person’s rejection by most of society for the “impossibility” of being two things simultaneously to illustrate how other members of society have been rejected for similar reasons: being of both Korean and Japanese heritage (a source of ethnic rejection and abuse), of being both loyal citizens and pro-democracy (many of the Gwangju protesters were arrested, imprisoned, and sometimes executed for being stooges of the North Korean government), and so forth—and how much of those hostilities remain within Korean society and to what degree they are changing for the positive.