I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: I arrogantly recommend…

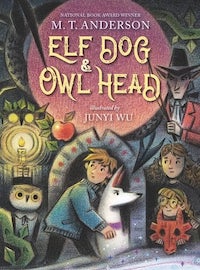

Elf Dog & Owl Head

M.T. Anderson with illustrations by Junyi Wu

Candlewick Press

Elphinore is a dog of the People Under the Mountain, magical people of royal lineage who keep hidden from people who live on the land. During a hunt for a wyrm—a large, snake-like creature—the pack of hunting dogs Elphinore lives among continue their pursuit from under the mountain to the outside, protected from human sight by magical spells. Elphinore, a smart and curious dog, becomes distracted by the exotic human world—with its highways crammed with speeding cars and a gas station with its strange odors—and is separated from the rest of the pack, unable to retreat under the mountain again.

During the recent pandemic, a young boy named Clay discovers the dog, plays with it, and brings it home, where it is quickly adopted by the rest of Clay’s family, including his two sisters, DiRossi and Juniper. School is an online-only affair and his mother’s job at a local diner is on pause. Only the father’s job on the Road Commission still takes him out of the house. Otherwise, Clay is as bored as his sisters, and they tend to spend their time snapping at each other. The appearance of Elphinore brings a much-needed change of pace to their lives, although as finder of the dog, Clay assumes authority over her.

Soon after Elphinore becomes part of the household, she and Clay discover during a long walk a house filled with owl-headed beings, who recognize Elphinore as a dog from Under the Mountain but leave her be since the Owl Heads are their enemies. Before Clay sneaks away from the grounds of the owl’s house, he filches a small wooden container shaped like a saltshaker. It was with this container that an owl shakes its contents onto the yard, from which emerges a garden of ripened vegetables. When Clay returns home, he absentmindedly sets the shaker aside in the bathroom while washing his hands, and it ends up being used by other members of the household who mistake it for something else. Soon, magical things start happening (no spoilers here), including a late-night visit to the house by a child owl-person named Amos who ends up befriending Clay. Amos knows about the shaker and he knows where Elphinore comes from.

Amos, Clay, and Elphinore begin going on adventures, exploring the empty fields and hills around them, usually in the magical spaces between worlds—that of Clay’s and of Amos’s and Elphinore’s. The idyll is ended when the escaped wyrm of the novel’s beginning attempts to take Clay as its next meal. Disaster ensues, forcing Amos to take Clay and Elphinore to his village, where Clay’s and Elphinore’s wounds may be tended. Amos is punished, no longer able to meet with Clay.

Clay, too, ends up being grounded by his parents, because the adventure with the wyrm involves the loss of a metal detector owned by the county that Clay’s father works for. Since Clay is forbidden from going into the forest, his oldest sister, DiRossi, decides to walk Elphinore, certain that Clay has been keeping secrets from her about cool things he may have discovered on their walks. DiRossi is a 14-year-old who listens to “sad girl” music and is prone to sudden mood swings between bouts of teenage sullenness. Well, soon enough, DiRossi and even Juniper, the youngest sibling, all have made the acquaintance of Elphinore’s magical world, including Amos, who asks them to pass along to Clay an invitation to a party on Midsummer’s Night, when the barriers vanish that separate the various worlds.

At the party, the People Under the Mountain discover their lost Elphinore and immediately kick and drag her away. A posse on horseback heads out to trash Clay’s house in retaliation. I’ll avoid spoiling how various of the story’s strands are resolved, suffice it to say that Elphinore doesn’t require any Old Yeller-type of shotgun blast to the back of her trusting head, and the story’s ending offers the potential for future adventures. (A fantasy counterpart to Anderson’s Pals in Peril pulp SF series?) Junyi Wu’s illustrations capture the story’s excitement, balancing danger and assurance in each image. Elf Dog & Owl Head lie more on the fun side of Anderson’s narrative spectrum than his National Book Award-nominated and -winning titles, such as Feed and The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, but is as good a place as any to start reading his impressive body of works.

M.T. Anderson discusses the dog who modeled the novel’s hero

Interview with M. T. Anderson

For the past 20-odd years, M. T. Anderson has been publishing books for children and young adults on a wide range of topics—from music to mythology—in numerous forms—from biography to science fiction—and moods—from silly to somber. If awards, honors, award nominations, and best-of lists each had a physical weight to match their intellectual gravitas, I suspect his house would be in serious need of structural support: The National Book Award, Best YA Books of All Time lists, Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, Best Books of the Year lists, and so on count as some of the recognitions he’s achieved. His writing pretty much represents the gold standard of books for young readers (and adults) including Feed, The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Vols. I and II, Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad, and Landscape with Invisible Hand (now a film, too).

How did you discover your knack for writing to and about children and young adults?

I always wanted to write books for middle-grade readers and young adults—even when I was a teen myself. The experience of reading was so fundamental to me, transforming boredom into enchantment, that I was eager to take part in that process. When I was sixteen or seventeen, I tried to write a middle-grade novel based on a dream I had about a mountain covered in metal. Years later, I revised that novel and it became my book The Game of Sunken Places.

What rhetorical choices are required of writing for young adults as opposed to grown-ups?

People vary so much in how they approach writing for teens! Is there any hard and fast rule? I guess there tends to be a little more explanation of emotion and motivation. Some people would say that a book for teens has to contain hope. But I’m not sure that there are specific rules I can recommend because there are so many different ways to write for young adults. Each book has its own rules. You as a writer have to learn them as you write it.

Could you explain how your travels around the world and your love of music refresh and support your narrative interests? While Symphony for the City of the Dead, about the composer Shostakovich, is of course about music, your musical interests go beyond symphonies, Russian composers, and 20th century music. To what degree does travel and music inspire ideas for stories and how much reflects research for ideas?

Music is absolutely central to my life. Music of the distant past, music of the present, music of the future—I think about it a lot. Music has been with me in my moments of greatest sorrow and I’ve thrashed around to it in moments of my greatest joy. Because music transcends spoken language, it seems powerfully intimate, deeply private, like the voice of the mind in solitude, when we no longer have to pretend. In particular, I’ve found that the world’s classical musics—from the first large-scale pieces of human music we can actually decipher (the Chinese guqin repertoire, which may date from as early as the 2nd or 3rd centuries CE) to Elizabethan consort music to modern symphonies written by people negotiating political action and political repression—this music really speaks to me because it seems as if I am feeling the pulse of the dead in my own veins.

I use those visions of the past and of other minds in my writing, but not in ways that would be immediately obvious or interesting to a reader. When I’m preparing to write a historical novel, for example (or real history, as in the case of the Shostakovich book), I listen to music from that period and try to ingest the cadences they’re used to, try to hypnotize myself, I guess, to think the way they’d think for an hour or two. I try to remove myself from who I am and my knowledge of my world. That’s something music, painting, all the arts can do so well: releasing us from the prison of what we know.

What sorts of questions and comments do you receive from kids who read your books, and what do those responses tell you about your audience and their concerns?

Whoo—all over the map, since I get notes from kids as young as 7 and as old as 78. I get letters with adorable pictures of my characters drawn on them from younger kids, but I also get letters from teens who are in really tough spots, looking for someone they can open up to. One thing this has taught me is that you can never know what someone will get out of your book. In my novel Landscape with Invisible Hand, for example, the main character suffers from a gastric syndrome modeled on Crohn’s Disease. A few years ago I got a note from kids in a summer camp for kids who suffer from Crohn’s thanking me for highlighting it. Their camp slogan was “Shit happens.”

In addition to Elf Dog & Owl Head being released this year, the film version of your novel Landscape with Invisible Hand has also been released. Can you talk about what’s in the works from you in the future?

Next year, an exciting moment: My first novel that’s just for adults,Nicked,is coming out in spring 2024! It’s the dramatization of a real event: a heist in which a bunch of thieves stole the corpse of St. Nicholas, Santa Claus, and took it back with them to Italy because they believed it oozed a liquor which would heal anyone who drank it.

But while I was doing the research for this novel, I discovered a whole other trove of untapped info about this incredibly weird caper—and I regretted not being able to use it in my fictional version. As a result, I am thrilled to say I’m currently writing a non-fiction book for teens about the Santa Claus theft for Dutton! It will be out in two years, I think. I’m still arguing with forensic scientists.

Can you describe the working relationship you have with Junyi Wu regarding, say, how the scenes are selected to illustrate, the mood you want to convey, etc.?

As often happens in children’s publishing, I didn’t meet with Junyi Wu before she began work at all! The art director facilitated all of that. The moment they showed me her work, I knew she was the right one to capture the kind of classic, dreamy feel of the book. I occasionally made comments on the sketches—but most of my comments were basically that all the ears had to be bigger and more pointy, and that the People Under the Mountain should be more 19th century or 1920s than medieval. She did a beautiful job. I love the sweep and intensity of her work.

Who are some authors/books you think that are overlooked or insufficiently appreciated, either for young adults in particular or for readers of any age?

Don’t get me started. How about: 1. Hey Jane Austen fans! Read Fanny Burney! 2. Hey people forcing teens to read Uncle Tom’s Cabin! Read Henry Bibb’s Narrative instead! More exciting and actually by a black person! 3. Hey people looking for an unusual young adult novel! Read Daniel Pinkwater’s young adult novel Young Adult Novel! 4. Hey people who think the novel has to be about huge conflicts and vast emotions! Read Sayaka Murata’sConvenience Store Womanor Sara Levine’sTreasure Island!!! (the exclamation points are part of the title). They’ll convince you the inner world of one eccentric character is world enough for a novel.

While We Were Dreaming

While We Were Dreaming

Clemens Meyer / Katy Derbyshire

Fitzcarraldo Editions

When the Berlin Wall falls, a group of boys—Daniel, Rico, Paul, Walter, and Mark—are 13 years old and living in a poor quarter of Leipzig—that is, living on the East German side of the wall. The notion of “liberation” is not part of their world view, and the wall’s fall does not bring about immediate economic prosperity to those born and raised in the German Democratic Republic. Its industries are Soviet-era, devoted to producing cheap, poorly-made and -designed goods no one has any use for, especially now that citizens can buy better-made goods from the West.

Before the fall, when the boys are around 8 years old, their fathers have jobs, often as skilled laborers. But the fathers vanish along with their jobs, and by the time the wall comes down, parents—fathers and mothers—are well into alcoholism, regularly engaging in physical abuse of each other and their children. Chronologically, the major events during the 10 years or so covered by While We Were Dreaming go as follows: Industry leaves, families dissolve, the wall comes down, schoolrooms shrink as students and their parents leave for the West, and those left behind form gangs, leading to juvenile jail, adult prison, and death (although death often comes before prison).

Coming into Leipzig with the wall’s fall are pornography, better-quality cigarettes and alcohol—and heroin, pills, and cocaine. As in Scorcese’s Goodfellas, the boys’ sordid lives only worsen once hard drugs become available. But before the hard stuff kicks in, the teenage boys are content with smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, and beating up members of competing gangs. In the space of a just a few years, the 13-year-old boys transform from cute with rough-and-tumble edges, to unemployable violent criminals with drug and alcohol problems, finding themselves in and out of hospitals, drunk tanks, and jails by age 16.

Daniel Lenz is the novel’s moral center—or as moral as conditions in his neighborhood allow a person to exhibit and remain alive. But of all the characters, he is the one who tries to stop or avoid fights with other gangs, to stop or avoid robberies, beatings of parents who beat their children, and so forth. Before Germany is reunited, he is an academically promising lad and patriotic Young Pioneer; after its reunification, he becomes a hapless observer of his and his friends’ declines into mental illness and death. Theirs is the “no future” sung about 15 years prior by England’s Sex Pistols.

Dreaming’s nonchronological structure builds upon the emotional impact of what the boys endure. Rather than lead anarchic lives filled anomie and violence, they (individually and collectively) would prefer goals, responsibilities, and recognition. To that end, at around age 15, they create a techno club in the shell of an abandoned factory, decorating the walls and stairwells with reflective tinfoil and little lights, setting up a makeshift bar, and hiring a DJ whose fans span gang affiliations. But the club ends up being destroyed by a jealous gang from another neighborhood. On another tack, one boy adopts a dog and devotes his energy and money taking care of the dog, even ensuring its health to the care of a vet—all at the expense of the alcohol and cigarettes he would otherwise buy. That, too, comes to a bad end. Another of the gang, Rico, hopes to become a boxer and trains diligently for the opportunity, but those dreams are quashed as well. Collectively and individually the boys’ hopes for a sense of dignity and self-respect are crushed at every turn. There is no room for solace in their world.

By the time the novel ends, only Rico and Daniel are left standing, Rico on his way to a lengthy prison sentence, Daniel desperately trying to keep his full-time job, not break his parole, avoid violence, and salvage of himself what he can to give shape to something like hope.

Beijing Sprawl

Beijing Sprawl

Xu Zechen / Jeremy Tiang + Eric Abrahamsen

Two Lines Press

Beijing Sprawl comprises nine stories connected by three main protagonists, young men in their late teens, high school dropouts who have left their small villages for the fortunes and promises of life in Beijing. Without a college degree or skilled training, however, their prospects are low of finding well-paying, meaningful work, as are their odds of finding a girlfriend or wife. “Making it” in Beijing is often an endurance test that many young adults abandon after years of trying, ending up back in their home villages. The narrator, Muyu, is a 17-year-old who has come to Beijing to work for his uncle, Thirty Thou Hong, pasting up ads for his uncle’s fake-ID business.

Muyu ends up meeting three other guys in a position similar to his—Xingjian, Miluo, and Baolai—and they end up renting a small room with two bunkbeds in a dilapidated, unkempt building. When they’re not working, the boys eat donkey burgers (!), drink alcohol, and play cards on the rooftop of the slum they’re living in.

A few words for American readers who may be unfamiliar with China’s laws: First, inner migration—movement from one part of the country to the other for reasons of employment—is restricted so that a person moving from a village to, say, Beijing, must be sponsored. That is, an employer or relative must vouch for the migrant’s presence. Being sponsored is not the same as having official residence—the person’s official residence is still his hometown. This means that although the migrant pays city taxes, he has no access to tax-supported benefits, which includes everything from the ability to check out books from libraries, to schooling for children, to receiving health care. For the non-resident, all those benefits are additional out-of-pocket expenses. (Which, of course, the immigrants are too poor to afford.) Non-residents without sponsors are subject to immediate arrest and expulsion at any time—which may amount to being dumped off somewhere in the countryside. (Common aspirations include fantasizing marriage to an official resident of the city.)

Second, American readers may be surprised to find out that death by murder or accident results in little financial gain for grieving families, with settlements amounting to less than a year’s wages. (I’ve been told that, should the victim survive with lifelong medical conditions afterward, the perpetrator is required to pay the victim’s medical expenses for the duration of the victim’s natural life. Just killing a person outright is often less expensive than coping with the endless financial drip of the victim’s needs.)

The stories in Beijing Sprawl illustrate these facts in addition to slices of life among the down-and-out, ranging from the absurd to the tragic, with absurdities slowly turning into tragedies as the book progresses. Regarding the former, in “Wheels Turn,” one of the friends gets a job at an auto repair shop, where he accumulates junked car parts and eventually builds a functioning Frankenstein of a car from mismatched parts. The car brings the shop a lot of attention and business, but it eventually brings bad luck to a person who borrows it.

Midway through the book, Baolai falls in love with a woman he’s only ever just seen in the window of a diner, too shy to approach her. Baolai ends up the first of the friends to return to his village after his attempt fails to rescue the woman from the clutches of three men who drag her from the diner onto the street. The thugs give Baolai a beating that leaves him a drooling zombie, incapacitated in mind and body. From there on, a subplot of each story revolves around finding a replacement for him in the apartment the boys share. The would-be replacements include another village boy who tends to his uncle’s pigeons, another who claims to be looking for his “other self” (not a twin but another part of himself his parents had always told him lived in Beijing), and a busker whose attempts to rescue a trafficked 10-year-old girl come to a bad end.

The stories add up to a picture of contemporary China and the people who live in a place with more people than meaningful work, where staying fed and housed by honest means is a daily struggle, and government institutions insist that poverty is an individual choice. Jeremy Tiang and Eric Abrahamsen’s rendering of these stories into idiomatic English imbue them with an immediacy that highlights their relevance and humanity and transcends their specific political-geographical origin.

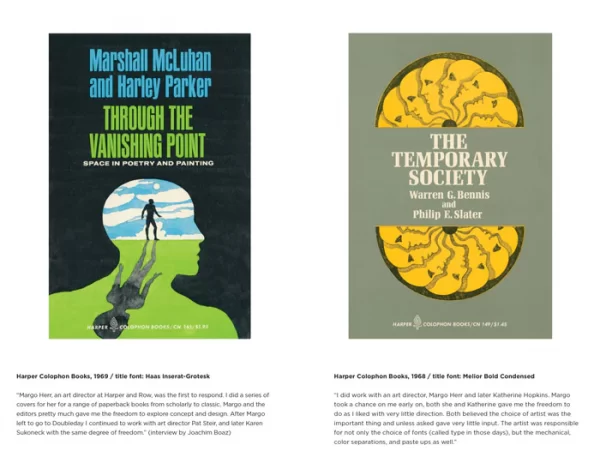

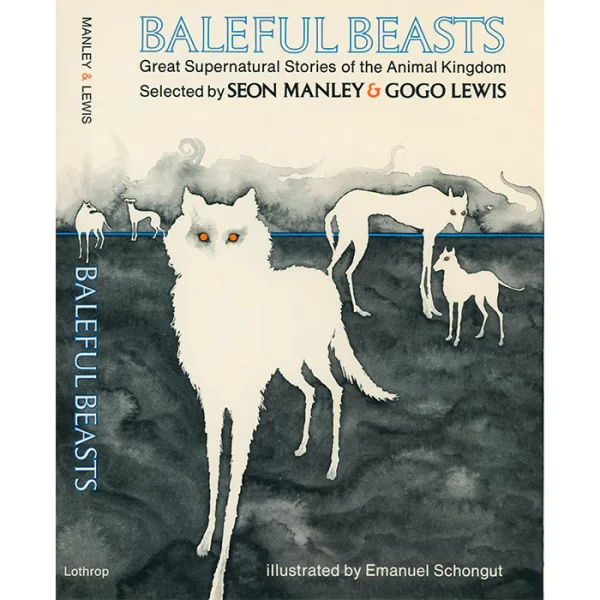

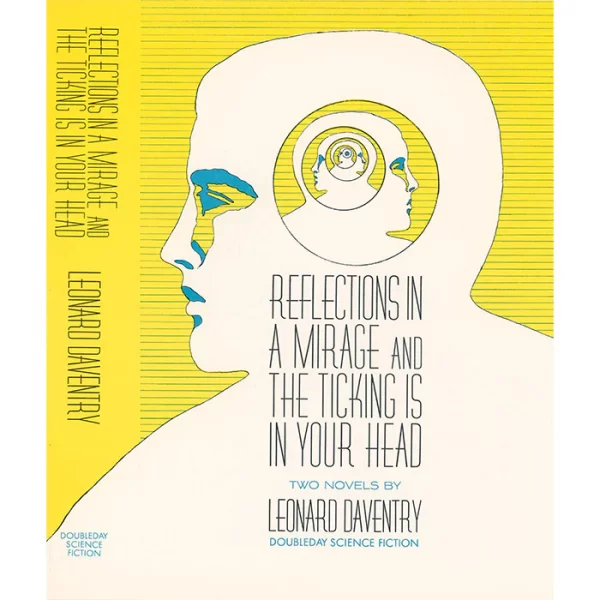

50 Watts Zine: One—Book Covers

50 Watts Zine: One—Book Covers

Emanuel Schongut

50 Watts Books

A full-color zine on glossy, heavy-stock paper devoted to, in the case of this first issue, book covers by Emanual Schongut designed in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s (yes, expect psychedelic effects throughout). Mostly for science fiction and mystery titles, Schongut illustrated and designed the covers’ layouts, and selected (or drew) the title and author fonts to reinforce the mood suggested by the pictures. The pictures themselves often employ a light line with rounded edges that give their objects an airy, balloony feel. Some books require something spikier, for which Schongut supplies wolves, spiders, and shadows. Fans of graphic design will no doubt enjoy this mini-anthology, both for the illustrations and for the brief paragraph that accompanies each on how they came about and the fonts used.

The Martian LSD Experiments

The Martian LSD Experiments

Assmann

Alienist

As the book’s title promises, The Martian LSD Experiments is a hallucinatory account of a future, allegorically like our present. Its introduction also serves as a premise for a role-playing game:

A psychocivilisational experiment has produced an evolved Corporate-State apparatus in which all social & political relations are fatally entrapped inside an hallucination.

In such a world, in which the irreal has become the last viable human habitat, inhumanity represents the final refuge of ‘ideological struggle.’

Set in a semi-abandoned mining operation on Mars, the novel begins with a cadre of people—including the author, Assmann, and several of his avatars—under attack for obscure reasons from various creatures and robots. Part of the struggle is against an intrenched bureaucracy. Anybody who’s had to endure work conferences can probably relate to one of the problems Assmann faces, i.e., “that the others in the room were all delusional, yet their delusion was that they were each reasonable individuals.”

The first few chapters of the LSD Experience introduce new perils for the characters to overcome, which slowly reveal the threat level the cadre operate under and the context for the threats: Think of historical parallels to colonization and the current state of tensions between the Israeli government and Palestinian people. Although the cadre are destroyed by the end of each chapter, they find themselves reanimated in the next chapter, in the same place but with the rules changed and the dangers increased, much as in a computer game. But the conflicts grow weirder and more overtly political and hallucinogenic as the chapters go by.

The whole off-world lifesupport system was one great war machine forever ready to swing into action the moment the algorithms aligned & someone like her punched a code & someone or some thing in higher authority pushed a button, pulled a trigger or flipped a switch. . .

“You should be fucking the System, not making it look sane to all those credulous idiots out there who wouldn’t know a hadron from a hand job. . . Only way to fuck the System’s from inside. THERE IS NO OUTSIDE!”

Can Assmann and his cohorts break free of this cycle?

My Work

My Work

Olga Ravn / Sophia Hersi Smith + Jennifer Russell

New Directions

Olga Ravn’s newest novel, My Work, is presented as a series of notes and poems written by a woman named Anna during the three years or so that occur between the end of her pregnancy and her son’s toddler years, years that Anna claims to have no recollection of, years lived in a fog of anxiety and detachment from the child she bore. Even a mere witness to childbirth, as I was to my daughter’s, can see that birth is less a miracle of nature than a full-on immersion into scientific procedure and sterility with a high-tech gloss unamenable to peace and intimate quiet.

I’m interested in the gap between the established truths we tell each other about pregnancy, childbirth, maternity leave and childrearing, and how people actually feel. I think a lot of unnecessary problems arise from this place. The incongruity between the story about childbirth and childbirth itself.

Anna’s emotions roil: she feels trapped, resentful, and suicidal. Although she dislikes the demands nursing places on her, sucking away her individuality, she doesn’t believe the baby is ready to stop and she insistently places his needs first. Motherhood erases her sese of self—with or without her son, she feels incomplete. Anything not related to laundry, cooking, buying clothes—anything not related to maternal duties is lost in a fog of barely-registered consciousness.

I write from a braindead place. Without aim. Without connection. Without recognition. There’s madness here, and exposed flesh. This is why no one wants to read the books of mothers. No one wants to know her. To see her become real. But if we don’t look, we live stunted half lives, each isolated in loneliness, shamefully pushing strollers down the boulevards and suburban streets, between the apartment locks and through the cemeteries amongst the dead.”

Combining poetry, diary entries, thumb-nail biographies, and technical information, My Work wavers from present to past across different stages in the child’s life and life before pregnancy. Her experiences cause Anna to doubt her capabilities as a mother and as a person trying to maintain her sanity.

Bottle-feeding is like gazing at the sea, whereas in breastfeeding I become one with all water in the world. Without time, without love, without civilization. In the depths of breastfeeding, I’m lost and displaced, part of timeless nature. . . If the child falls asleep at my breast at night, he lies still and sleeps deeply. But after a night bottle, he kicks off the duvet, babbles in his sleep, is like an underwater creature just hatched from its egg.

Even two years after the birth of her son, Anna is still plagued by anxiety over world events, pollution, toxic materials that damage young minds and bodies, sudden falls, parental competency, and so forth—and still harbors occasional thoughts of suicide. With this twinned body—herself and the child she birthed—comes a twin consciousness never at rest, often at war with itself. Anna is in a type of physical and psychic interzone—both being intensely in the present, anxious about the future, while also feeling neither here nor there. Every event and thought are up for examination. Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell’s translation deftly and sensitively lend Ravn’s poetry and prose a coherence these disparate thoughts and emotions resist.

When the child left my body, the whole world transformed, not a single living thing could be understood in the same way again. Among the world’s objects was now my child, my own literal flesh, looking back at me. My connection to the world changed radically. Every single thing in the world revealed another, deeper side, because part of my body had left me and now existed among them. I was no longer the same. The divide between what is me and what is the world opened. Everything casts the same light as before, but now I see that it’s living.

During the last quarter of the book, after Anna has demanded of her husband two hours a day that she can dedicate, uninterrupted, to writing, the novel becomes interrogative, questioning the cultural tropes that demand of women peak happiness and contentment in the state of motherhood. She explores the experiences described in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Edgar Allan Poe’s attitudes towards women (!), and Mary Shelley’s and Ito Hiromi’s experiences as mothers and writers. She looks at the biographies of other women writers, some with children and some without, to see how they coped and how their coping was perceived by others. Eventually, an emotional equilibrium sets in, a contentment, a sense of ease—finally, again—in inhabiting her own body and mind.

Just in time for another pregnancy.

Written on Water

Written on Water

Eileen Chang / Andrew F. Jones

NYRB

Originally published in 1944 when Chang was 24 years old, Written on Water shows a young writer’s talent developing essay by essay, akin to (but different in style from) Charles Dickens during his early “Sketches by Boz” phase, when he cultivated his writing chops beginning with simple descriptions of persons and events, a skill he eventually expanded by sewing together disparate characters and situations onto a plot. Chang was born and raised in Shanghai, the daughter of a prosperous but wayward father, an opium addict, and a devote mother, eventually cast out of the home along with Chang herself.

As a member of an affluent Chinese family, Chang witnessed the tensions caused by modernization, which often also meant Westernization—tensions between men and women (women of Chang’s generation began demanding equality in education and rejected the notion of concubines and practice of binding feet), and following traditional, Confucian ways versus adopting Western ways, including everything from fashion to music. Chang aimed to attend the London School of Economics for reasons of expanding her education and escaping her parents’ acrimony toward each other. That hope ended with Japan’s invasion of China, when travel to London was impossible, and she ended up at a new college for women in Hong Kong, where she studied for three years until the war came to Hong Kong and made further education impossible. She then returned to Shanghai.

In Written on Water, Chang explores subjects mundane and grand, from food to fashion to painting, music, literature, her family and her rearing. There are descriptions of street scenes and smells—food cooked on sidewalks and in restaurants, people traveling by in rickshaws, etc. In a long essay on Chinese fashions, Chang discusses their origins and significance, how and why they change, and what they say about the roles women (mostly) and men in society. “Speaking of Women” begins with several pages of quotations from a pamphlet called Cats describing the (disreputably) qualities of catty women, then examines the quotes less for their truth value than for what they say about women’s motivations for acting as the quotes suggest they do.

Her essays on Chinese films examine the representation of women’s roles in society and marriage, especially as concerns the practice of polygamy among men and monogamy among women. As China modernized, it was influenced by the West, and this influence was expressed as, first, an acceptance of women receiving an education, then, second, an insistence upon it. Polygamy began dying out as its hypocrisy towards love and marriage became less acceptable—many men and women were appalled by the idea of women approaching sexual relationships with the same ardor as men, even though they were open to increasing amounts of equality between the sexes in other areas of social and domestic life. . . She also explains what she enjoys about Peking opera and why it differs so much from the social realities everyone else lives—it’s an idealized version of a time that never was.

In “Unpublished Manuscripts,” she trots out portions of stories she wrote while in middle school and high school. Although heavy on adjectives, clichés, and generic tropes (Chang admits that the stories are wretched), their ardency and level of craftsmanship show the potential talent of a young writer learning through imitation, and doing well at that, especially given her age. During her early twenties, when Chinese authors were urged to write stories about the proletariat, she found (in “What Are We to Write?”) that she had no capacity for doing so, since she had no experience or understanding of their lives. Her prosperous family hired amahs (maids) to do the domestic work, which gave her some sliver of insight into their lives; however, amahs were not considered members of the proletariat (probably because of their proximity to wealth).

As the essays parade by, Chang’s writing feels less tentative and more assured, especially, by the time of “Whispers,” in her ability to capture the life of a prosperous Chinese family midway between traditional aspirations and Western sensibilities as well as Chang’s own temperament as an indulged daughter. Some women still have bound feet, her father has a concubine and an opium addiction, Chang and her brother receive a classical Chinese education, but Chang nevertheless develops tastes for Western literature and fashions. “Whispers” deals in part with her contentious relationship with her father and stepmother (also an opium addict) and her fondness for her mother, divorced and kicked out of the house. Legally, Chang is required to live with her father, but after a severe beating from her father followed by imprisonment for half a year in her bedroom, Chang escapes to live with her mother.

“Unforgettable Paintings” and “On Painting” are exercises in ekphrastic composition, interpreting in vignettes the mood, setting, and meaning of several paintings by Chinese and European artists, in the former, and by Cézanne, in the latter. The many descriptions in “On Painting” sound like one-paragraph excerpts from a book that was never written—a testament to her increasing skills as a writer, that she could provoke readers to want to know more, to have the dots connected into a whole that was never there.

Her powers of observation, insight, intelligence, and wit, and her sense of nuance and complexity in the emotions of lovers and family members are the qualities Chang’s novels are known for and which Andrew F. Jones’s translation deftly conveys. Written on Water allows readers to see those talents as they blossom.

Pleasure of Thinking: Essays

Pleasure of Thinking: Essays

Wang Xiaobo / Yan Yan

Astra House

Wang Xiaobo was a Chinese writer who died at age 45 in 1997 and whose works are only just now being translated into English. (See my review of his novel Golden Age.) Wang was a sent-down youth during China’s Cultural Revolution, when millions of urbanites—entire families—from the middle-class and upper class were “sent down” to the countryside to toil in collective farms, a practice which lasted from the late 1950s until 1976. (Wang was sent down during his teens, presumably because of because of his father’s academic background.) The essays collected here express his views, often tinged with irony, on a variety of topics, from sociology, to literature, to homosexuality, to living as a grad student in the U.S. during the 1980s, and more.

For instance, surgery during the Cultural Revolution was performed without access to electricity or hygienic conditions by men [sic] who had no training in or knowledge of medicine—the doctors had all been sent down too on account of their college background. Wang also writes on sociological studies written by Li Yinhe, his wife, and published in mainland China regarding feminism, homosexuality, and heterosexuality. Although his dated comments on feminism may discomfort some readers, the discomfort owes more to cultural differences between East and West that give rise to different questions regarding gender, natural aptitudes, and responsibilities than the often monolithic, one-size-fits-all approach towards those topics as discussed by mainstream feminists in the West. The conclusions of Li’s studies of homosexuality (for which Wang was a co-author) won’t come as a surprise to Westerners—the government’s ideological claims aside, homosexuals have always been a part of China’s population, and at rates similar to the rest of the world—but comes as an uncomfortable truth to many (officially atheist) Chinese, even today, whose hostility toward homosexuals is as oppressive as any Western practitioner of one religious orthodoxy or another.

For a course in anthropology Wang took in the U.S. as a graduate student, he worked in two Chinese restaurants owned and operated by naturalized Chinese nationals. The point of Wang’s anthropological study was to explore the Chinese immigrant story for immigrants who came to the U.S. as unskilled laborers. It serves to introduce to Chinese immigrants U.S. working conditions and explain to U.S. readers how those experiences are understood by immigrants.

The final essay, “The Silent Majority,” bookends nicely with the second, titular essay, “Pleasure of Thinking.” Wang reflects on the role of silence versus speaking out on important topics. During Wang’s formative experiences of the Cultural Revolution, opining on any given topic—especially those with political ramifications—could result in public ridicule, beatings, torture, and death. Very few people knew who they could trust without fear of repercussion, so their public personae did not necessarily represent how they felt. The Cultural Revolution exacerbated a cultural tendency that favored keeping mum over risking looking foolish. As a result, Wang speculates on the nature of a Chinese silent majority, masking a mass of discontent—implicitly with, if not the Communist Party, then at least its leaders and administrators.

Writing and speaking truthfully provide their own pleasures, of course, but safer are the pleasures of thinking, free of persecution and condemnation, and which, in written form, allow us to communicate and develop hope with and among kindred spirits.

O

O

Tammy Nguyen

Ugly Duckling Presse

Combining art (the author’s own), music, history, cultural critique, and autobiography, Tammy Nguyen’s O explores the layers of her extended family’s immigrant experience, ranging from the U.S. war against North Viet Nam to property development to spelunking to dental implants, to pottery and painting. How she connects these disparate people, things, and experiences—how she brings her story full circle to the O of the book’s title—is what makes this memoir fascinating and insightful.

O is a major addition to diasporic literature. Already an accomplished artist, who has exhibited internationally, Nguyen proves herself to be an equally powerful and engaging writer. O belongs on a shelf with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée and Sophia Al-Maria’s The Girl Who Fell to Earth: A Memoir. — John Yau

Palookaville 24

Palookaville 24

Seth

Drawn & Quarterly

Palookaville is back! Seth’s sporadically published serial “comic book” returns a couple of years after the publication of the complete Clyde Fans, chapters of which had been serialized for years in the pages of earlier Palookaville installments. Part an examination of the lives of various denizens of Seth’s invented town, Dominion (presumably somewhere in Ontario, Canada), part chronicle of Seth’s other ongoing projects (often physical realizations of some aspect of Dominion or its inhabitants). I had assumed—wrongly, I am happy to report—that the finale to Abe and Simon Matchcard’s decades-long, desultory mismanagement of the family business (selling oscillating fans) did not mean the end of the Palookaville series, too.

Palookaville 24 comprises three sections: the fourth installment of “Nothing Lasts” (autobiographical snippets about growing up in semi-rural Canada); photographs from the filming of “The Apology of Albert Batch,” a puppet show designed, built, and performed by Seth (and included as a DVD with the book!); and excerpts from his sketchbooks, which show how he turns a set of prompts (list provided) into stories.

The book is excellent. Seth seems to have reached a creative apex in which story ideas and their layout seem to flow effortlessly from his brushes. Visually, every page of “Nothing Lasts” is a surprise of design in which the story’s emotional content is conveyed by the mutual support the story’s words and images lend each other—a surprise but always understated and never garish. Even though “Nothing Lasts” is in its fourth chapter, knowledge of the previous installments is unnecessary for understanding and appreciating it. Strongly recommended for those who appreciate excellence in graphic design, storytelling, and/or cartooning.

Offshore Lightning

Offshore Lightning

Saito Nazuna / Alexa Frank

Drawn & Quarterly

Saito Nazuna writes and illustrates a type of manga called gekiga, a form devoted to depictions of everyday life, rather than the fantastic and super-hero tales most American devotees of manga are familiar with. Nazuna is also unusual in that her career as a manga artist didn’t begin until she was 40 (she was born in 1946), when her first published story garnered an honorable mention in a national competition held for novice manga artists. Given her starting age, it’s no wonder that her gekiga concern the lives of common people—neither rich nor poor nor well-positioned in prestigious occupations—exploring the relationships between men and women, middle-aged children and their elderly (often hospitalized) parents, and include prostitution to earn income above subsistence level (pearl divers by day, geishas by night), children born out of wedlock to concubines (still a thing in Japan, apparently), job insecurity, and economic calamity. You won’t mistake it for Pokémon.

The book’s penultimate tale concerns a family of siblings who compare notes after each of their regular visits to their mother, a woman who is wasting away in a nursing home, with dementia, osteoporosis, and an anger toward her children, hospital roommates, and approaching death that only increases. In the last story, the protagonist—an older woman—lives near an apartment building filled with elderly people biding away their days until death. But they are living as much as they are dying, tending to stray cats, helping each other with chores, keeping an eye out for each other. It is in death that the author finds joy in life, in life’s mundane chores and little friendships. Just in time, too, because she’s run out of stories and no longer has the energy to compete with young manga artists who lack her insights into life’s triumphs and indignities.

The Limit

The Limit

Rosalind Belben

NYRB Classics

Rosalind Belben’s novel The Limit, first published in England in 1974, is about a couple who married late (Anna was 40 and still a virgin) and now, 20-odd years later, finds the wife slowly dying of a stomach tumor in a hospital, daily tended to by her Italian husband, Ilario, who loves her deeply. He is a sea captain, often away for months at a time, but never tempted to stray, and he spends the entirety of each day at her bedside when she sickens. It’s not clear how Anna spends her time while he is at sea, but she’s used to being alone and seems unfazed by his absences.

Seamlessly interweaving first-person narration from Anna’s and Ilario’s viewpoints plus that of an omniscient narrator’s, The Limit explores the physical and emotional marriage of two people at the end of one’s life. The book’s first half, in which their thoughts confusedly entangle, are reminiscent of Ann Quin’s Three or Tripticks, except that in the case of Belben’s novel, husband and wife love each other.

Between this short book’s beginning and end (it’s only 100 pages) are memories of their lives before they met, during their childless marriage, and emptying the house after her death. As an Italian, Ilario is referred to by his in-laws as “the wop,” and he won’t be missed by them, no matter how well he loved Anna. At the hospital, they both endure the usual degradations of a failing body cleaned by a patient, loving hand; he at the end of what he can stand. Depending on one’s age and marital satisfaction, Belben’s descriptions of Anna’s wasting away can be difficult to face—as much as one in love must, nevertheless.

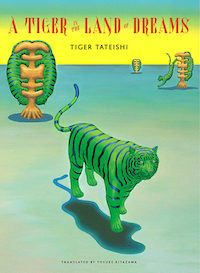

A Tiger in the Land of Dreams

A Tiger in the Land of Dreams

Tiger Tateishi / Yosuke Kitazawa

50 Watts Books

What do tigers dream about? Japanese graphic artist and children’s author Tiger Tateishi explores this question through the dreams of Torakichi, a green tiger with blue stripes who sleeps vertically along the side of a brown, trunk-like structure with truncated branches. When two tigers nestle themselves between the branches, it looks like a tree. A Tiger in the Land of Dreams follows Torakichi across a dreamy landscape in which other green-and-blue tigers emerge from blocks of melting ice. Curled up, the tigers look like watermelons; unfurled, they wander among enormous mazes formed by abandoned ruins, and so forth. It’s picture book for young children that encourages dream time as a time to explore the weird and mysterious rather than fear them. It asks readers to develop their imagination, to be courageous in the face of the strange and nonsensical, to find joy in ambiguity.

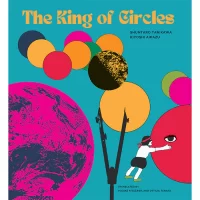

The King of Circles

The King of Circles

Suntaro Tanikawa + Kiyoshi Awazu / Yosuke Kitazawa + Ottilia Tanaka

50 Watts Books

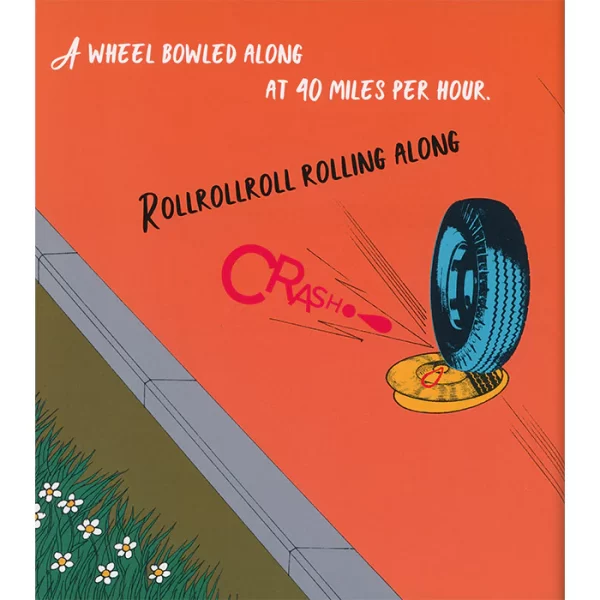

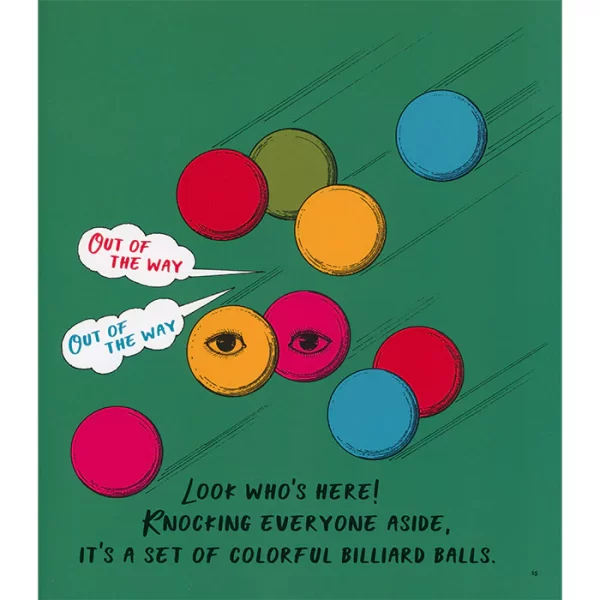

Aah, the life of a child’s mind, when almost everything in its world is new and fascinating and vast, full of potential excitement and discovery. The early childhood fascination explored here concerns the wonders of geometry and learning to distinguish and categorize the different types of shape. In The King of Circles, writer Suntaro Tanikawa and graphic designer Kiyoshi Awazu explore the qualities of roundness, from circles to spheres, including such non-round objects as protractors, which can create circles. Beautifully colored and designed, the book takes the eyes on a tour of objects familiar and unfamiliar to young children. From the plates they eat from to the moon in the sky, from flat to not-quite spherical (tires) to spherical, each object illustrated vies for the title of King of the Circles.

When Dad’s Hair Took Off

When Dad’s Hair Took Off

Jörg Mühle / Melody Shaw

Gecko Press

I never thought of using this children’s book’s premise for explaining my own condition: “Dad’s hair was sick of being brushed and combed. It was tired of hanging around on his head. It wanted a life of its own. It wanted to see the world.” And with that, Dad’s hair evacuates his scalp, out to see the big, wide world—to explore such places as the Sahaira Desert and Hairizona (yes, the tale takes a hair-pun turn every chance it gets), and Jörg Mühle demonstrates a verbal imagination akin Calvino’s and brush line with the whimsy reminiscent of Guy Delisle’s absurd tales of fatherhood.

Meantime, Dad isn’t passive about his abrupt balding. He pursues his delinquent hairs across the globe, to no avail. They even send him mocking postcards from destinations they’ve seen. Will these prodigal hairs ever return?

To Melody Shaw’s credit, all the puns she had to translate succeed in sounding like naturally spoken English. She’s also succeeded in rendering the translation as one that demands to be read aloud. For kids 1st through 3rd grade.

Les Aventuriers du Ciel

Les Aventuriers du Ciel

Raymond Houy

Ion Edition

Les Aventuriers du Ciel (“Adventurers of the Sky”) collects 26 cover illustrations by Raymond Houy for a science fiction novel by René-Marcel de Nizerolles first serialized in France from 1935 to 1937, then re-issued between 1950 and 1951. These are the covers to the re-issued serial, which Houy had also illustrated during its initial run. Installments include titles that translate to “To Unknown Worlds,” “Arrival among the Martians,” “The Revolt of the Automatons,” “The Magic Boat,” “The 8-Headed Monster,” and so forth, featuring encounters with dinosaurs, mammoths, robots, and, well, 8-headed monsters. One sky adventurer looks surprisingly like Larry David, which lends an extra unexpected absurdity to the covers. Nothing lurid here—everyone is fully clothed, even when imperiled. Two full pages written in French in tiny print summarize the storyline, which, based on the cover images, seems to consist only of one damned thing after another. Recommended for fans of adventure stories and old science fiction iconography.

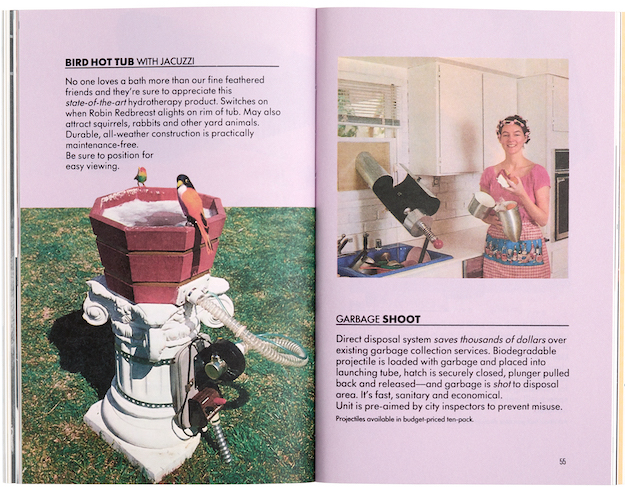

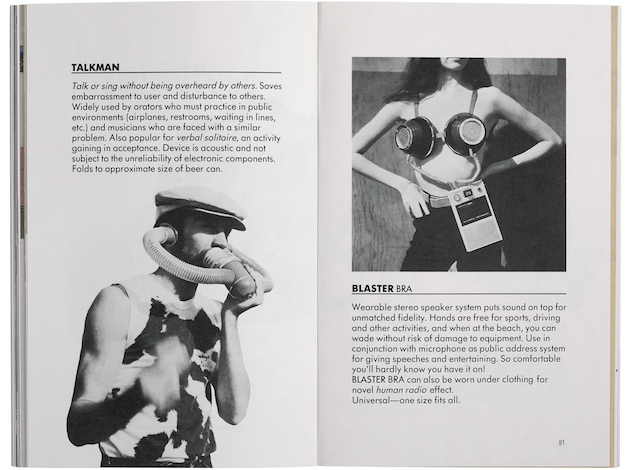

Better Living Catalog: 62 Absolute Necessities for Contemporary Survival

Better Living Catalog: 62 Absolute Necessities for Contemporary Survival

Philip Garner

Primary Information

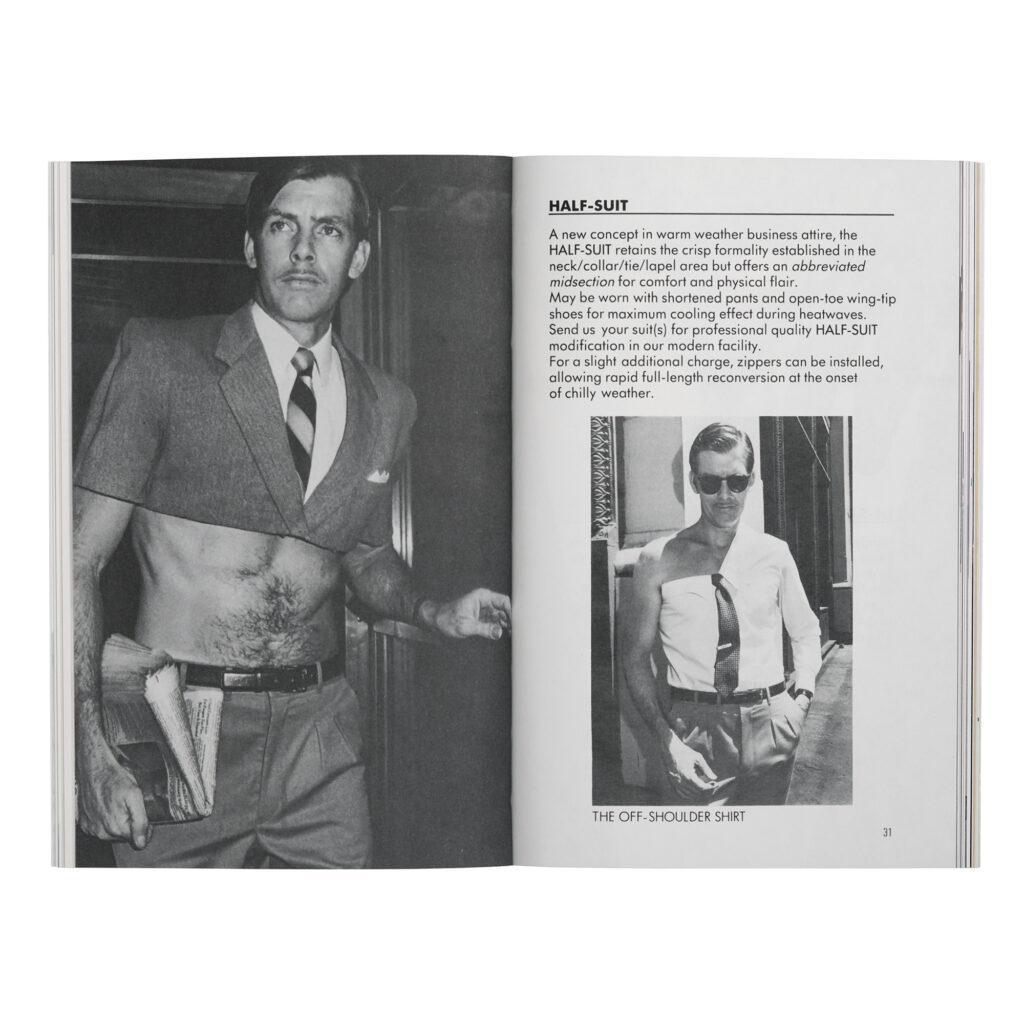

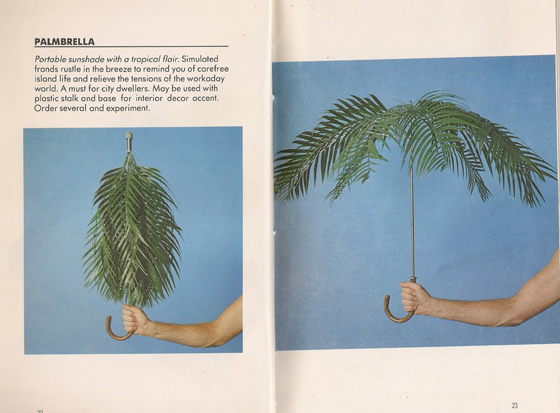

Occupying a place somewhere between Hammacher Schlemmer and Carol Wright catalogs hawking items of dubious aesthetic and technical value, the inventor and artist Philip Garner’s Better Living Catalog compiles profiles of 62 impractical gadgets designed with user convenience in mind. Most of the items depicted remind me of inventions some of my freshmen engineering students come up with—nothing anybody with a scintilla of sense would buy, but cobbled together a la Rube Goldberg just to see if the students can transform their half-baked ideas into something functional. I’ve often smugly thought to myself that C-average students end up in dildonics—the design of sex toys—but Garner shows that the world of questionable goods is even broader and funnier than I originally imagined.

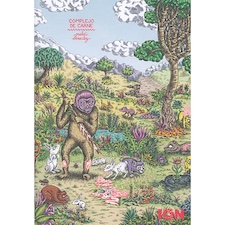

Complejo de Carne

Complejo de Carne

Mehdi Beneitez

Ion Edition

Artist Mehdi Beneitez creates detailed images of a natural menagerie of creatures—red in tooth and claw—like a spikier, cruel version of Jim Woodring’s illustrations. The world of Complejo de Carne (“meat complex”) includes eyeless bunnies, suppurating wounds that drip upward, discarded intestines, creatures with faces like sockets (male and female couplers), insects that look like fruit and vegetables, exposed crania, and other horrors of nature. (It seems that the more urbanized humanity becomes, the more fear-inducing the natural world is.) Richly detailed in hallucinogenic color, it’s an assemblage of images for fans of the weird.

Alienist was an English-language journal of art, fiction, and cultural theory out of Prague. With 30 contributions from Europe, the U.S., and Australia, this tenth issue of Alienist includes collages a la Barbara Kruger and essays influenced by post-structuralism, all engaged in cultural critique of capitalism and authoritarianism, ranging from the snarky to the soberminded. In line with the journal’s anti-capitalist ethos, the run of Alienist publications is available for free as PDFs, or they may be purchased in print form.