I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, small press and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles are unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help. Many of Mr. Bowden’s suggestions are stocked at Book Beat. Thank you for your support! Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:I arrogantly recommend… And if you’re near the area stop by Book Beat on Indie Bookstore day Saturday, April 28. Mr. Bowden will be there between 2-3 pm and will happily match your personality to his list of weird and unique books!

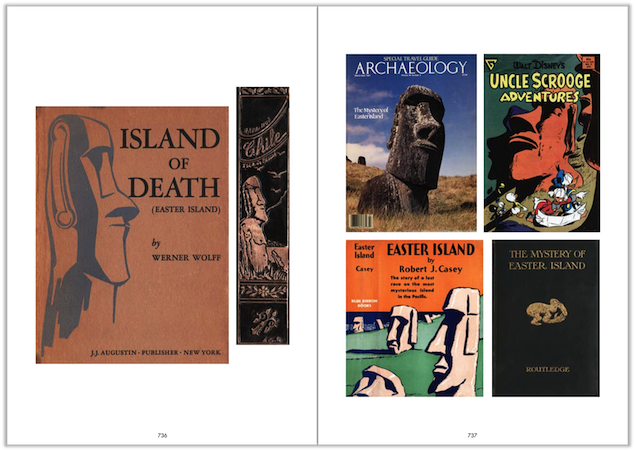

Library

Glenn Bray (Ed.)

Art Works Fine Art Publishing

Over its 800 pages, Library reproduces, in glorious full color, thousands of covers from Glenn Bray’s collection of books, magazines, pamphlets, tracts, brochures, and other ephemera. In lieu of a systematic approach, the images are organized by common theme or design, the theme changing every one to three pages, ranging from Nazis to UFOs, from high-brow architecture publications to low-brow wrestling magazines, and so forth—a fabulous cornucopia of layout designs and color and lettering choices on media targeted to everybody from children to adults. Trigger alert: Because this is a sample of popular culture across the 20th century, it includes words and images many people will find offensive. As a cross-section of American culture, these offensive images represent the times that produced them, and Bray’s intention seems to favor showing popular attitudes, warts and all.

Highly recommended. One hopes a second volume ensues, as teased about at the book’s end. Order directly through the store or from Glenn Bray himself at gbray@socal.rr.com

[Ed. note: Read Glenn Barr’s interview on his earlier collection Scrapbook. Signed copies are still available.]

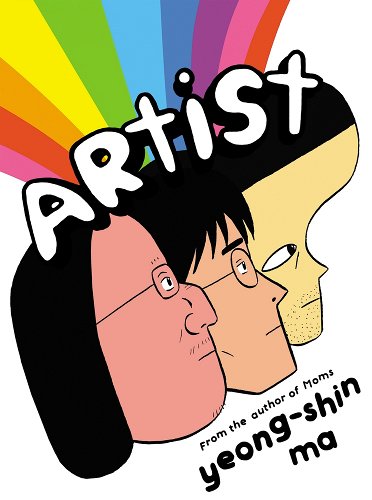

Artist

Artist

Yeong-shin Ma / Janet Hong

Drawn & Quarterly

Three men in their mid-40s trudge their way through mid-life pursuing careers in the arts that have left them far short of success, however that term is defined. An artist, musician, and writer— Korean men now in their mid-40s but without steady sources of income or influence in their various fields—decide at the start of the year to make their final push into renown and acceptance. The “final push” amounts to showing some measure of dignity and self-restraint for the first time in their lives. Not everyone is up to the challenge. The straights these guys find themselves in at the beginning of the book were familiar to me as attributes of myself and my friends during our twenties, so the wake-up call seems to be arriving rather late in life but arrives, nonetheless. Their actions vary from moving to embarrassing as they begin reflecting on their actions, motivations, and long-standing friendships. Prominent awards and positions are offered, declined, and revoked as the men attempt to navigate among status symbols and what they actually want from life

Red Flowers

Red Flowers

Yoshiharu Tsuge / Ryan Holmberg

Drawn & Quarterly

Red Flowers is the second volume from Drawn & Quarterly to focus on the onset of Toshiharu Tsuge’s mature period, when he and a few other illustrators helped transform Japan’s comic book world. Realizing that the technical and dramatic structuring skills of cartoonists often equaled that of artists approved by “the establishment,” Tsuge began writing and illustrating a series of stories roughly based on his travels through the Japanese countryside, post WWII, where he encounters people living at unelectrified substance level, much as they had been for centuries.

Tsuge’s stand-in travels the countryside, describing his various encounters with villagers and innkeepers, combine realist backgrounds (betraying an excellent sense of draftsmanship) with, well, cartoonish-looking people (but not to the exaggerated extent current manga has). While Tsuge’s illustrations also evoke a sense of eerie wonder—perhaps as a result of the folktales and ghost stories that were popular in Japanese literature during the 1920s and ‘30s—his anecdotes often depict ephemeral moments of compassion between the protagonist and whoever he encounters, be it an escapee from a mental institute or a young woman experiencing her first period.

Includes an excellent introduction, co-written by Ryan Holmberg (also the book’s translator) and Mitsuhiro Asakawa, who provide biographical background and place Tsuge’s work in historical context.

________________________________________

China from the Cultural Revolution to Uyghur Mass Imprisonment

Modern history has not been kind to many mainland Chinese citizens: ten years of Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), a night of mass murder 13 years later at Tiananmen Square (1989), and now (since 2014) the ongoing imprisonment of Muslim Chinese, members of an ethnically Turkic group called Uyghurs. None of these topics may be publicly addressed in China that in any way challenges the authority or wisdom of the Communist Party and its policies.

Starting about 15 years ago, though, writers who lived through the Cultural Revolution during their youth, many now at or soon reaching retirement age, began writing fictionalized accounts of their experiences, published in Mandarin by state-approved publishers on the mainland. While in the late ‘60s U.S. students were protesting the war in Viet Nam and tossing tear-gas cannisters back at police, Chinese students either were in the Red Guard publicly humiliating and beating older local authority figures (including parents and relatives) or “sent down” to the countryside or a decaying industrial center to accompany their parents and / or perform manual labor under primitive conditions, all in the name of “re-educating” them out of their “bourgeois” values.

From what I can tell—from what I don’t see in these books—Chinese authors who publish in Mandarin on mainland China (as the following three authors do) may depict the Cultural Revolution realistically, so long as neither Chairman Mao nor the Party (or any of its specific members) are criticized or implicated in the inhumane crimes committed against fellow citizens during this decade. Instead, in these novels anonymous members of the Red Guard are blamed for the actions. Even today, regarding its poor handling of food distribution during the many weeks’-long shutdowns of the pandemic, the Communist Party blames overly avid Party members at the local level for “misinterpreting” the Party line. One might think that, after 80 years of chronic misinterpretations, party leaders might feel a vested interest in determining why such conditions exist. But who am I to be critical?

Tiananmen Square and the mass imprisonment of Muslims cannot be addressed at all, whether or not the government is invoked. The Tiananmen Square massacre can only be addressed in roundabout terms, with adjectives and adverbs selected for allusive purposes but without nouns that might imply a time, place, and circumstance. Although the Uyghur author Perhat Tursun was allowed to publish in Uyghur, that was before Xi’s crackdown. While Tursun’s novel The Backstreets reads like a mash-up between Kafka and David Lynch, my guess is that subsequent books from Xinjiang will read more like the autobiographical accounts of men and women who escaped from North Korea.

Golden Age

Golden Age

Wang Xiaobo / Yan Yan

Astra House

The Golden Age’s three chapters occur at important points in Wang Er’s (the protagonist’s) life: turning 20, 30, then 40—transition to adulthood, mid-life, and reflective seniority. (Yeah, I know—he’s only 40, but it works here, presciently so.) Given the novel’s rootedness in events occurring during and because of the Cultural Revolution, the chapters describe life in a re-education camp, later integration into society, and reflection on a life lived during national turmoil and through its aftereffects.

Wang Er is 20 years old when the novel begins, living—intermittently—on the grounds of a re-education camp. There, he meets Cheng Qingyang, a doctor, and the two become lovers who leave their assigned work teams to eke out a living in the forest. Upon their return six months later, they are forced to write a confession describing what they were up to. The cadre leaders urge them to confess treason but will accept sex out of wedlock, especially if the confession is, um, well-written. Golden Age’s author Wang Xiaobo describes a punishment system that is corrupt and based on whimsy rather than the rule of law. Team cadres don’t need to worry about those who have been sent down running away from the camp territories because sent-down individuals have no money or food, and need government approval to live where they go. In that sense, the prison is the entire nation.

But it’s a prison in which Wang and Cheng have lots of sex.

Wang and Cheng continue living on the communal farm as part of their punishment for infractions against the Cultural Revolution but are saved from worse punishment by the quality of Wang’s written confessions about their sex lives. The only criticism of substance the Revolution committee members offer Wang is to avoid euphemisms for sex and confessions in which sex does not occur. Wang’s ability to satisfy these demands, while satisfying the erotic drive he shares with Cheng, prevents the two from being executed for their bourgeois ways. Even though they could run away, Wang and Cheng decide that life is easier together on the prison farm, where they can still have their way with each other—and neither seems bothered by the fact that everybody knows, in detail, what they do and how they do it. None of their neighbors resent them for what they do. In fact, their confessions, as written by Wang, are why they are so popular in the prison, even among top administrators. Something, of course, must change this.

The second story, “At Thirty, a Man,” occurs ten years later. Now 30, Wang Er is a hapless university lab instructor, mourning his lost chance at an overseas sabbatical. Looking for a bar in which to grieve, he bumps into an old flame, returns home late, is beaten by his wife, and, the next morning, falls asleep at a faculty meeting. The story ends with Wang Er coming to terms with his temperament. Since his every attempt to behave in a manner accepted by authority figures ends in disaster, Wang must choose whether to follow the path set by his temperament or that of the “proper course”—and accept the consequences.

Here is one of Wang Er’s ongoing mistakes that leave him questioning his career. Important university officials plan to inspect the biology lab’s building and facilities as part of a regular sanitation and cleanliness program, the toilets for which Wang has written “big letter” banners. (Big letter banners were banners that could be as long as a couple of stories tall, painted in large letters either quoting / praising Mao or denouncing various local neighborhood residents. In the example shown below, Wang Xiaobo parodies patriotic banners.)

“Welcome to the toilet!—Biology Lab.”

Above the urinal, I posted “Step forward, please—Biology cordially invites you to.”

On the back of the bathroom door, it read, “Farewell. We know you will come to miss this immaculate environment, but unfortunately it is time to work. When shall you return? Adieu from the Biology Lab.”

“Years as Waters Flow,” the last of the three stories, begins 10 years after the second story, when Wang Er is 40 years old. Only in midlife but written with a wistfulness aroused by his life during the Cultural Revolution and the fates of two professors he knew during that time at a mining university, one who committed suicide and another who was severely beaten.

The murderous part of the 10-year debacle is largely lacking from the first two stories, which cast the Cultural Revolution in a light close to that of “Hogan’s Heroes”: Wang Er gets away with acting and talking in ways that seem to have lead many others during that time to jail sentences, public beatings, and death.

“Years as Waters Flow” is more serious than the first two stories in expressing the dangers of the Cultural Revolution. Not everyone during these years was worked up into an ideological frenzy. The story also offers, as one written from the viewpoint of a 40-year-old, a more sympathetic picture of older characters than was available to the imagination of a 20-year-old of limited experience, especially as regarding the older men and the humiliations they suffered both from ageing in a country with poor medical care and being the target of revolutionary zeal, as resentful youth clash against the privileges that come with age in a traditional Confucian culture.

Wang Xiaobo died at age 47, ten years of which were lived under the duress of the Cultural Revolution, where he was assigned menial work in the countryside. In this final story he reflects,

Among the dead are my friends. They wanted to become martyrs but they became silly cunts. A story like that is far too tragic; I don’t have it in me to write about it. If I asked for a true pen of history to write the years as water flow, I would have already committed the sin of phoniness.

I know even more tragic tales—from what I can see, life’s greatest tragedy lies in being duped. Will there ever be an end to those tragedies?

Ninth Building

Ninth Building

Zou Jingzhi / Jeremy Tiang

Open Letter

Ninth Building begins in November 1976 as a group of friends travel to a fabric dyer to order 21 Red Guard armbands. The Red Guards were the enforcers of Mao’s whims, consisting mainly of young people in their teens and twenties. Revolutionary excitement is in the air when the book opens, building upon the rising tide of violence against “rightist” and “bourgeois” elements in society and rising suicide rates among those targeted for the violence. Enhancing the excitement is the opportunity for children to denounce their parents or watch relatives take beatings from Red Guard soldiers. Betraying family and neighbors, blinding following orders, engaging in public humiliations and beatings of others—all the hallmarks of a government that, in lieu of functioning, keeps its citizens perpetually fearful.

Ninth Building contains stories about hard work on communal farms; deaths of animals, babies, and adults; gambling and fighting; and playing in an orchestra on a diet of cabbage soup, where errors in performance are taken as acts of anti-revolutionary sabotage. As a metaphor for how the grueling work affected those being punished, here’s a passage describing the life-cycle of musical instruments brought to the farms by trained musicians:

Come the spring, when you went to visit the violin, a family of mice had made their home in its case. The velvet lining had been ripped to shreds and turned into a nest. They’d sharpened their teeth on the strings, and tunneled their way through the sides. The belly of the instrument now held a mound of wheat and corn. Everything had changed. There was no more music, and when you touched the violin, it no longer made a noise.

Planting, harvesting crops, chopping down trees, surviving six months of winter at a time in primitive buildings with inadequate supplies of coal, dying from unhygienic conditions—and taking time in the midst of this to compose music. Ninth Building is a stoic account of people bound together in their imprisonment, enduring a period that wasted a generation of talent.

A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts

A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts

Wang Yin / Andrea Lingenfelter

NYRB Poets

Wang Yin is a poet, art critic, and photographer from Shanghai born in 1962, a poet of the “post-Misty” school. The “misty school” consisted of Chinese poets who rejected Communist Party restrictions on their poetry during the Cultural Revolution, producing work that is often obscure or vague in meaning. Perhaps the term “post-Misty” is meant to imply a continuation of obscurity but this time in the face of the Tiananmen Square massacre of June 4, 1989, in which thousands of protesters for democracy were slain or wounded by government soldiers. This is a topic that still may not be discussed, at least not in public.

A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts is described by translator Andrea Lingenfelter as Wang’s “first comprehensive edition in English”—and what an excellent collection it is. Presented mostly in reverse chronological order with Chinese and English versions on facing pages, Lingenfelter’s translations stand on their own as well-wrought poetry. Often speaking about something indistinctly described but specific in feeling, the poems nonetheless resonate beyond themselves. Beginning now and unreeling back to the Tiananmen era, the reverse chronology shows a sympathizer from the time, now reaching retirement age—the point at which the ripples in a wake are at their furthest from the initial splash, to which the collection works back.

The specificity of mortal loss described in the first stanza of “The Mariner Loses His Love” leads to the moral loss implied by the second:

The mariner loses his love, watches his ship slowly sink

The king sits on his throne, as his country is laid waste

On the road with its swirling dust

I take out a handkerchief, examine the white fibers

Tears are a chariot without a driver

and without wheels

but there’s a strong wind blowing its endless suffering

into the shadows of spring

Of course, I’m primed to read, in the first stanza, “love” as “idea for a better form of rule,” “ship” as “China,” and other images as allusions to Tiananmen square and its emotional after-effects. A rudderless country in which “endless suffering” is about to meet spring, a time of hope in rebirth.

Well, that didn’t happen.

Instead, citizens were allowed to make as much money as they liked, as long as they didn’t tell the government what to do. Affluence will buy a lot of complacency. Those who participated in the Tiananmen demonstrations paid the price of living through an experience nobody wants or is allowed to talk about. But the din of the past is loud.

You tell me you miss those

slow-paced days of the past

the equally leisurely pace of bicycles

and leaky wrist watches

We’re both out of step with the times, lifting our old-fashioned cups of coffee

drinking a cup to Carolyn, another to poverty

drinking a toast to the season of mental confusion

another to the unrelenting snowfall

and another to the listening devices of yore

The last cup we drink is to ourselves

men out of step with the times. . .

So while I pause for a moment while writing you

it’s just me with my head in the clouds again

The moment I send the email, that’s when

the relentless wind and rain

come to a halt at last

The Backstreets: A Novel of Xinjian

The Backstreets: A Novel of Xinjian

Perhat Tursun / Darren Byler + Anonymous

Columbia University Press

In this garbage, many living beings were scurrying around. They were just like the people on the streets of the city: moving very quickly, bustling this way and that. The whole content of their lives, which was comprised of eating, sleeping, and procreating, seemed to resemble the lives of the people of the city as well. Those creatures, which we don’t even want to imagine, and which make us nauseous, were secretly enjoying eating, sleeping, and procreating—making a holy crime of living.

The Backstreets takes place in Ürümchi, the capital of Northwest China’s Xinjian Uyghur Autonomous Region—an Alaska-sized state with a Muslim-majority population, including a prison camp of about two million Muslim men and women and special schools for another half million Muslim children, all of whom are subject to (at least) China’s attempts to eliminate Uyghur language, history, and culture. Although comprising the majority population of the Autonomous Region, the best-paying jobs go not to Uyghurs but to the colonizing Han, China’s primary ethnic group, who recently moved to the area.

The anonymous narrator of The Backstreets works in an office where he is the token Uyghur, hired only because of government quotas, rarely spoken to and routinely ignored or dismissed when encountering troubles. He is equally ignored on the streets, which only increases his agitation and sense of isolation: “It seemed as though nobody would talk to me, but I couldn’t ignore the feeling that somebody might suddenly come up to me and say something.” Either ignored or under attack, solely based on ethnicity. “The choice to walk along any of the four streets was my freedom, but this freedom itself left me confused.”

Uyghur Muslims who follow dietary restrictions and commands to pray five times daily are characterized by the Communist Party as “extremist,” to the extent that even Islamic prohibitions against drinking alcohol are categorized this way. Extremism equals terrorism in this formulation. Unsurprisingly, alcoholism among Uyghurs has sky-rocketed since the internment camps began being set up in 2017.

As recently as 2014, when Xi Jinping, China’s current president, was the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi “urged the general public to turn terrorists into ‘rats scurrying across the street, with everybody shouting, ‘Beat them.’” Throughout The Backstreets our narrator encounters rats or objects he mistakes for rats, constant reminders—as if any were needed—of how he is seen by the Han around him. This doesn’t arouse the narrator’s sympathy for them—they are rats, after all, actual vectors of disease and misery.

Author Perhat Tursun is no stranger to cruel punishments for infractions against whimsical notions of law: one of his parents, a schoolteacher, was imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution for “counterrevolutionary” behavior. Tursun, however, ended up attending university in Beijing—one of a handful of other Uyghur students, living in a city where they were treated as less than fully human.

The Backstreets begins with the narrator walking the streets of Ürümchi, one of the world’s most polluted cities, with smog so thick it is impossible to see more than two blocks ahead. (Somebody I know who once traveled to the region told me that even inside a cab with its windows rolled up, his eyes stung and watered.) The pollution is described as a fog—an obscuring, imprisoning presence that permeates everything. The narrator is trying to track down an address to a potential apartment—his boss threatens to fire him if he’s caught again sleeping overnight in the office. In the meantime, we are privy to his thoughts and experiences as an unwanted human.

Tursun himself was disappeared by the Chinese government in 2017 and hasn’t been heard from since. One rumor says he is serving a 16-year sentence; another claims that he had been “hospitalized” by the government. Two anonymous Uyghurs who helped Darren Byler translate this book, whom he identifies by only by their initials, were also disappeared by the government after Tursun’s abduction. Tursun has left behind five incomplete novels.

________________________________________

Bosun

New Juche

kiddiepunk

Taking place in present-day Rangoon, Burma—as the author prefers to identify Yangon, Myanmar, out of deference to its time as a British colonial outpost, whose now-rusting and -crumbling, moss-covered buildings remind New Juche of the council housing of his youth, the British version of urban house projects, where corruption—physical and moral—is part of the dissolute atmosphere—Bosun serves as an apologetics of place delivered via words and photography, a Down and Out in Paris and London, minus the sense of being down or out or, if those senses still obtain, then the sense that down and out are the narrator’s preferred states of being: Living in a polluted and broiling city where heat and humidity are assuaged via drinking, smoking, and whoring.

W the Whore

W the Whore

Anke Feuchtenberger and Katrin de Vries / Mark Nevins

NYR Comics

W the Whore is a series of elliptical vignettes featuring W the Whore, a contemporary everywoman. W is not a whore in the professional or moral sense but in the way society treats her as a single woman. I thought of Laurie Anderson’s lyrics, “You were born / so you are free / so happy birthday”: What place does a “free woman” have in a world that is generally hostile to the very idea? Katrin de Vries provides artist Anke Feuchtenberger with text to illustrate. The text (succinctly translated by Mark Nevins) is terse enough to give Feuchtenberger ample room to imagine a series of actions to accompany them, as in a voice-over narration. Think The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’s Expressionism by way of Thomas Ott’s scratchboard narratives in the service of telling a feminist tale of living solo and female. Bonus points: Really nice production values from NYRB. Hope there’s more to be translated from these collaborators.

Anke Feuchtenberger, September 27th, 2022: https://youtu.be/oAnqetGx_m4

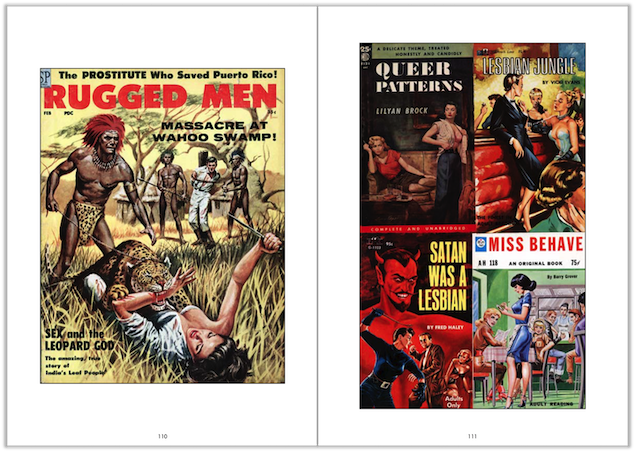

Sex and Horror

Sex and Horror

Volume Four

Korero Press

Another anthology the ongoing Sex and Horror series collecting covers from an Italian form of commercial art called “fumetti sexy”—pocket-sized comic books with lurid covers (and content) depicting gory males and females of exemplary physique engaged in various forms of violence and / or sex in historic, folkloric, and fantastic backgrounds suggestive of large budgets and the macabre. (The earlier volumes are devoted to specific artists. Volume four showcases work by a variety of artists.) Despite the NSFW, in-your-face sexual exploitation, and soft-core porn images, these pamphlets were sold throughout the ’60 and ‘70s at public kiosks. Louche, gauche, and delightful as only the finest in bad taste can be, most covers were painted by were formally trained artists who often had to crank out at least two covers a week, covers often depicting several actions at once, so that the eye constantly darts around the image, in some way reproducing the action of the image—the eye is as rushed as the artist.

Preexisting Conditions: Recounting the Plague

Preexisting Conditions: Recounting the Plague

Samuel Weber

Zone Books

Philosopher Samuel Weber’s Preexisting Conditions examines historical accounts of plagues written over the last two millennia, from the Bible to Camus’ The Plague. Weber holds that the degree to which a plague is effective has to do with a community’s “preexisting conditions”—that is, the social and environmental factors that allow plague germs to develop and spread in the first place. Nowadays, for instance, since the American healthcare industry is profit-motivated it thus tends to reject for coverage patients who already have or have already suffered from some recurring disease or its aftereffects. For Weber, this practice masks the underlying social and environmental conditions that give rise to pandemics and thus, by implication, help perpetuate such things:

The plague reveals that from a healthy point of view, as distinct from a profit point of view, the exclusion of ‘preexisting conditions’ is untenable, since these ‘conditions’ also condition the susceptibility to the pandemic, as to any other illness.

Ignoring social and economic conditions underlying any given pandemic allow “the social classes that benefit from such inequalities” to place blame for the disease on the victims, instead.

In fact, Weber shows, populations throughout history have reacted to pandemics by scapegoating different ethnic groups: The Spanish for the Spanish flu (which may very well have developed first in the U.S.), Jews for the black plague, and so forth. The ability to assign blame and guilt and “the desire to control and eliminate plagues by identifying their origins tends to deny their essentially relational dimension, which in principle cannot be reduced to a single cause or place.” Thus, pointing fingers at a lab in Wuhan, China—even if determined to be the source of the leaked virus—would still not address “the ecological and social changes in reducing the areas in which non-human life can exist, thus increasing the likelihood of zoonosis, that is, pathogens jumping from non-human to human organisms.”

Because discussions of the Covid pandemic were largely matters of polemics, they, too, must be considered as “preexisting conditions” that influenced “the underlying insistence on certainty and the growing incapacity to accept uncertainty.” Thus, again, even if the Wuhan lab is determined to have been the source of the Covid leak, “the Wuhan laboratory was supported by many international agencies,” so the scapegoat for the pandemic’s origins remains elusive—and irrelevant. Of relevance are forms of group behaviors (since plagues are social diseases) within and among each interconnected group that can mitigate any given plague’s spread.

To understand, discover, and/or illuminate the preexisting conditions that have allowed various plagues and pandemics to bloom and prosper, Weber analyzes, chapter by chapter, written accounts of various plagues and pandemics to see what of the experience is being expressed, how and why people acted as they did, what conditions give rise to anarchy, provide theological assessments of the morality of going or staying in affected areas, and so forth. Although the genesis of Preexisting Conditions preexisted Covid, its publication now is timely.