What Have You Left Behind?

What Have You Left Behind?

Bushra al-Maqtari / Sawad Hussain

Fitzcarraldo Editions

Bushra al-Maqtari spent two years interviewing civilians who survived attacks during the current ongoing civil war in Yemen. The civil war has been raging since 2014, apparently upon the insistence of the various warring factions, whose leaders are looting the country (even while living in exile in other Arab nations and Europe) and profiting well, despite the murders of 350,000 Yemeni citizens to date. The survivor narratives tell of attacks in which parents, grandparents, children, or fiancées were asleep or engaged in everyday activities when they were blown apart, shot, or abducted. Here are some opening lines:

“I’d barely been married two months when everything came to an end.”

“Their laughter echoes through this empty house.”

“When I’m awake, when I’m asleep, I hear their cries for help.”

“My sister says that my children’s murder turned me into someone else.”

“You were only a step from the front door.”

War is good for warlords, who deplete citizens of their life’s savings and produce neighbors who ransack other]

[ neighbors’ bombed-out apartments—even to the extent of pilfering goods while stepping on bodies buried under rubble. Each account ends with the full name of the person testifying, followed by the full names of each person killed or injured in the described attack, along with their ages, and relationship to the speaker.

In the last 50 pages of the book, al-Maqtari lists attacks on civilians during the civil war according to date, the faction that did the killing, and the number of civilians killed, including people tortured to death in prison.

What Have You Left Behind? is a memento mori for those trapped in a cynical theo-political system that works to deliberately perpetuate misery in the name of power.

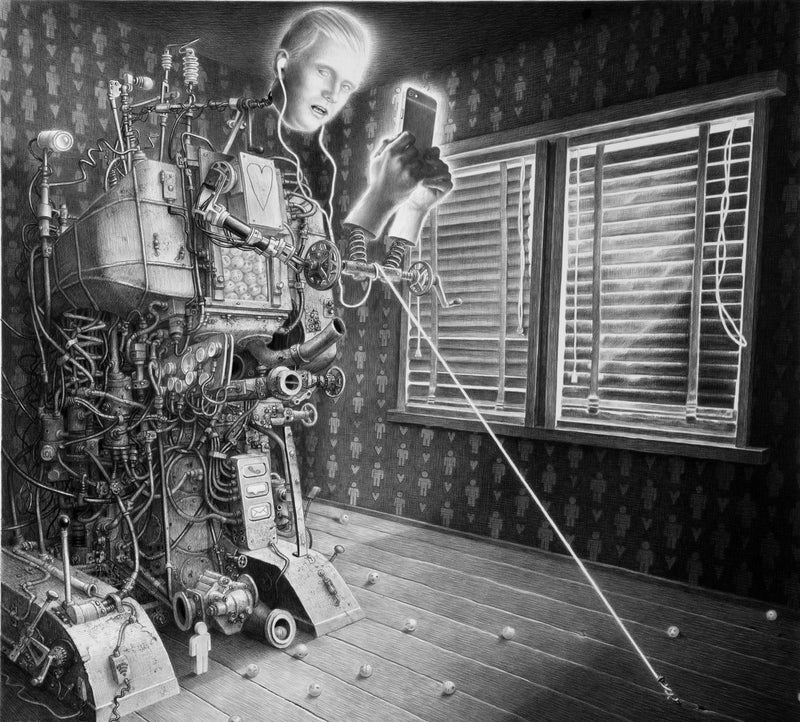

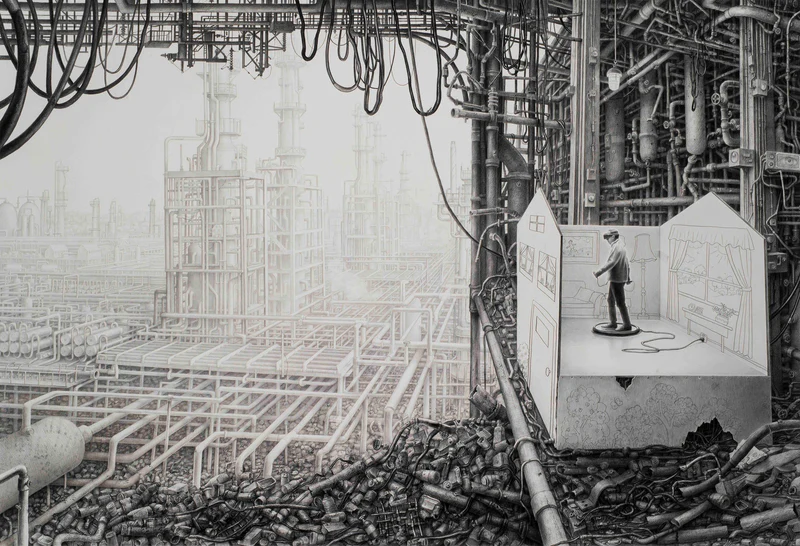

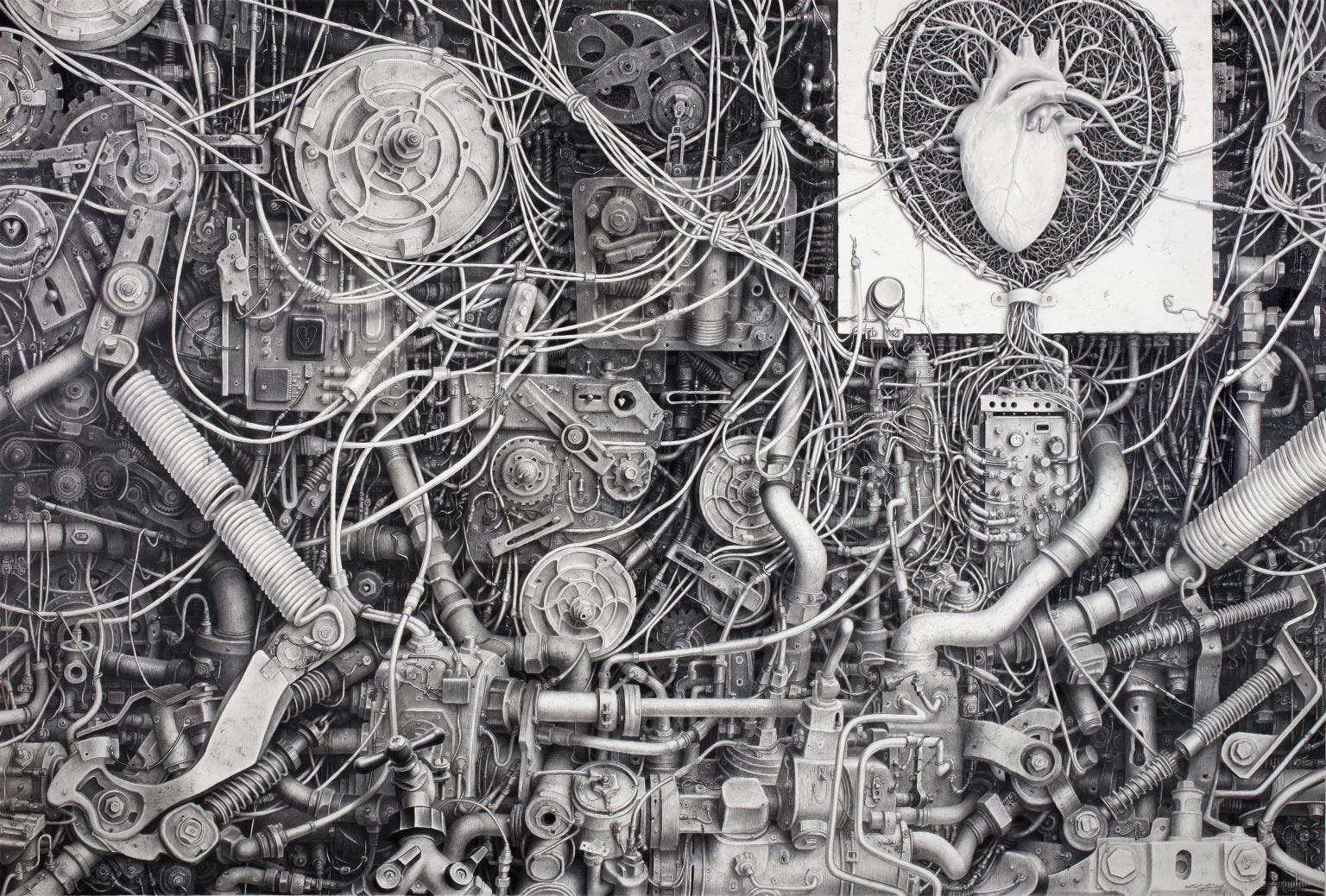

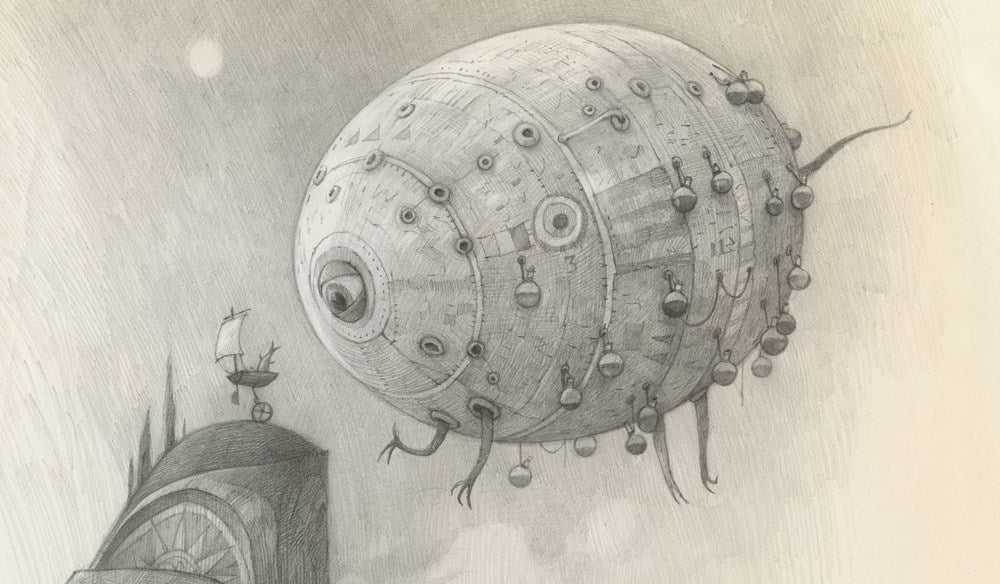

Drawing

Drawing

Laurie Lipton

Last Gasp

Laurie Lipton works in the terrain so well exploited by H. R. Geiger—a melding of (human) biological forms to mechanical/industrial production ends. Whereas Geiger focused on yoking feral sexuality to mechanical repetition, Lipton focuses on contrasting consumer fantasy lives with Dickensian images of urban industrial squalor. Like Geiger, Lipton works with a limited color palette—in Lipton’s case, pencil and charcoal, sometimes on a scale of 6’ x 9.’ The argument behind Lipton’s images is that the once liberatory role in individual human potential that the internet was supposed to provide in its wiki-valorization of free knowledge has led not only away from a utopian New Frontier but back to reproducing the misery of former times. Increased consumption leads only to increased misery, and Lipton’s pictures are allegories of our time.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Publisher Profile: 3TimesRebel

3TimesRebel is a new imprint out of England with a simple mission statement: “We translate female authors who write in minority languages. Only women. Only minority languages. This is our choice.” The following reviews cover their first three titles, two translated from Catalan, the third from Basque.

The Carnivorous Plant

The Carnivorous Plant

Andrea Mayo / Laura McGloughlin

This book should be read by everyone who has been in a relationship with a person with borderline personality disorder, whether parent, child, or lover. The storyline is simple: A woman, Andrea, finds herself increasingly absorbed into the physical and psychological orbit of Ibana (or Ib), an orbit like that of an object on the fringe of a black hole. Here, the fringes are the outer attractions that brings one person closer to another. But when told in retrospect—it’s hard to tell the tale otherwise given the cartoonish unreality of everyday existence with such a person—Andrea reveals a life that none of her friends or family knew of: a life with a person who constantly denigrates and denies, who picks battles when none are to be had, and introduces chaos into a life that could easily be otherwise. The denigrations include of self, of friends, of career, of hobbies—anything that might allow Andrea autonomy and a sense of escape—or the confidence to even try.

Ib detests her own family and Andrea’s family and friends, whom she, Ibana, tells to avoid or risk her wrath. Andrea is one who ignored all the warning signs, reconfigured the signs into something innocuous or—more likely—as her own faults, Andrea’s, that she brings to the relationship. Andrea lies to her friends about her relationship, cuts them off, lies to her family, cuts off her family, lies to hospital workers who suspect she’s been beaten, and avoids contact with others. . . And this goes on for three years. (It can go on substantially longer when children are involved.)

Although written allegorically, The Carnivorous Plant reads to me—as someone who once married such a plant—everything ring trues here. Except, I thought at first, except that the author, Andrea Mayo, doesn’t address the aftereffects: The fears and anxieties that linger even years after—in my case, the divorce with shared custody—putting one on constant edge that surely it’s time for another bad thing to happen. But although Mayo doesn’t directly address the echoing fears, it’s there in her name.

“Andrea Mayo” is a heteronym of Flavia Company. And Flavia Company blog is, according to Wikipedia, “degree[d] in Hispanic Philology, is a journalist, translator, teacher of creative writing and lecturer. . . works in . . . novel, short story, essay and poetry. . . publishes children’s literature. . . lives in Catalonia,” and—most crucially—”In June 2018, she embarked on a trip around the world that lasted four years. From that experience she wrote her book ‘I no longer need to be real’, which she signed with the name of Haru, one of her three heteronyms together with Andrea Mayo and Osamu.” Make of that what you will. But given the novel’s topic, readers should also consider the type of emotional and rhetorical distancing Company has made from the novel’s contents by framing the story as allegorical and the author as fictional.

I’d recommend this book to my daughters, but I think they’d find it too raw, despite the hopeful ending.

Dead Lands

Dead Lands

Núria Bendicho / Maruxa Relaño & Martha Tennent

Fans of such dysfunctional, self-destructive misfits from William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County as the Snopes family will find much of interest here, told in the manner of As I Lay Dying (in which each chapter is narrated by a different character, only easier to understand). Núria Bendicho’s Dead Lands begins with the murder of a middle child by a family member, a situation no one in the family will talk about after the fact. The story is hard to describe without spoiling key aspects of the novel, so let me offer a few generalities: (1) Move the setting from Faulkner’s rural Mississippi to rural Catalonia, near Spain. (2) The characters and motivations remain as they might be in Mississippi, only here they speak Catalan. (3) Plot elements: (a) Chronic intrafamily violence: Check. (b) Retardation and physical deformity within the family unit: Check. (c) Incest: Now enthusiastically consensual, although its nonconsensual form remains in practice, as do the predatory sexual instincts of authority figures outside the otherwise close-knit family unit.

Surprisingly enough, Bendicho (with the aid of translation from Maruxa Relaño and Martha Tennett) is able to arouse sympathy for members of a family stuck in an eternal cycle of violence boring through every aspect of their lives. For instance, we discover reasons why the mother of Jon, the murdered boy, doesn’t seemed much saddened by her son Jon’s death: a childhood spent with a father who had daily beaten her and her mother, eventually killing her mother (a point of contention later in the novel), then abandoning the daughter. After her father leaves, she walks to the farm where lives another 21-year-old like herself and proposes to the boy’s father to marry the boy, who eventually becomes Jon’s father. She exchanges one hell for another.

The humor here is bleak (as it is in As I Lay Dying): The family, unwilling to spend money on a coffin, stuff Jon’s corpse in a chicken coop too small for his body, requiring . . . alterations . . . to be made. And the mother’s send-off (a description of which would reveal too much) is also described by Bendicho with a narrative satisfaction similar to Faulkner’s jaundiced take on white trash yee-haw-ism.

Mothers Don’t

Mothers Don’t

Katixa Agirre / Kristin Addis

An exploration of the many physical and emotional aspects of that section of womanhood called “mother” and its all-encompassing demands—specifically, the subsuming of one’s own desires and identity to the needs of a child—that lead some women to kill their offspring. In this novel, a writer and mother of a 14-month-old child sees in the news a story of woman she once knew who has been arrested for the drowning of her twin children. What woman would kill her own children? For that matter, what woman would indulge in a casual affair for the duration of her pregnancy, as the narrator has? Intrigued by the murder case, the narrator contacts an old friend from college who also knew the woman when they were younger.

Impulses, attractions, repulsions, notions of responsibilities—and responsibilities toward whom and what and why, all in the context of being an individual and non-individual simultaneously, in the case of mothers. The narrator chooses to attend the trial of the mother, from which she will write the book we are reading.

Courtroom testimony from various professionals—psychiatrists, forensics, and police—ensue, as well as from the mother, her husband, and their nanny. Although the upside of the testimony from professionals is “these things happen” and that the “thing” that “happened” happens pretty frequently. One aspect of murderous post-partum depression the book seems to hint at is that in some cases murdering one’s children isn’t an irrational eruption of psychosis but a horribly a-rational act to preserve the mother’s self.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Trouble in Wonderland

Trouble in Wonderland

Kathy Reed

Book Baby

Trouble in Wonderland is third in Kathi Reed’s who-done-it series featuring Annie Fillmore, erstwhile indie video store owner (circa early 1990s) with an uncanny ability to find corpses piling up in unexpected places, giving her an excuse to apply her equally uncanny ability to sleuth and see that matters are set right judicially. In Trouble, Annie attends a regional distributor’s convention for indie video store owners held in a sleepy Kentucky burg. Inadvertently assigned an off-limits room, Annie opens the door and sees the chalk outline of where a corpse had been and the blood stains remain. Once she starts asking questions, she quickly stumbles upon a seething network of repressed resentments involving prominent members of the little town. What the motivation might be and what it would take to stop the bodies from piling higher is what Annie sets out to find out. Accompanying Annie during her stay in Wonderly, the small town the convention is in, are other video reps, an unexpected visit from an unexpected suitor, some of Wonderly’s citizens, her mothers (sic), and other diversions that add color to an otherwise sordid series of events.

The mortal violence is off-stage, blood only identified as such, swearing minimal, and sex thought about only as an idea people sometimes have. So be warned!

Interview with Kathi Reed

Mysteries come in a variety of flavors, from the tea-cozies of Agatha Christie to the intemperate foibles of Mickey Spillane—at any rate, writers from around the world have adapted the format to suit the needs of exploring dangerous territory in the name of moral balance. Plus, they’re lots of fun to read. Who were your influences, and which aspect(s) of their writing appealed to you the most?

I remember the first time Mom took me to the library to actually choose a book and not stand beside her while she was choosing one: my heart fluttered. I chose The Five Chinese Brothers. I think I chose it because the dimensions of the book were different than all the others: tall and skinny. Foreshadowing for sure. Not the size of the book, but because it was different.

I read a lot as a child, teen-ager-young adult; but when I had my first child I started reading mysteries. All of Agatha Christie (not just a tea-cozy in my opinion) but a dip into character in way to solve a puzzle. Then so many more: Ngaio Marsh, Patricia Highsmith—really too many to mention. After I first read Sue Grafton I thought, I can do this. Then I read Lawrence Blocks’ Bernie Rhodenbarr books, and thought I WANT to do this: Murder with a laugh.

Ongoing inspiration: Kate Atkinson, who in her crime novels, writes multiple stories and magically brings the pieces together as in a thousand-piece puzzle. So maybe, the puzzle is what intrigues me. Finding out what the heck is going on … kind of like life.

Not a crime writer, but Otessa Moshfegh, inspires me because she’s so absolutely fearless. I’m fascinated by her weird mind. Really, I have a crush on her writing.

How did your character, Annie Fillmore, come about, as well as her setting? Single, white woman, middle-aged owner of an indie video store, circa the early 1990s—just at the outset of the now-defunct Blockbuster’s abilities to put such competitors out of business. How’d she get there, and how long can her store last?

Annie got there because I got there. I owned a video store in the late 80s and 90s, and I started to write the idea for Trouble for Rent back in 1990. But running a business was all-consuming. The Mapplethorpe brouhaha really got my attention … and I decided I had to write about it—some day.

As the owner of a small Mom & Pop store and being in leadership positions within the video industry both locally and nationally VSDA (Video Store Dealers Association), I could see the writing on the wall. Mom and Pop stores were going to go–did go. I have plans for Annie’s store if I decide to keep writing the series. But there’s so much else I want to write; I may have to end it after a few more.

Do your novels re-cast true life crimes you’ve heard about, or do you begin with filling in different parts of the plot, or something else?

No, all the murders in my books are fiction. I’ve not (yet) based a murder on anything I’ve heard about. I begin filling in different parts of the plot as I go along. I’ve found I can get to about Chapter 13 when I think, oh wait! At that point I go back and start to line things up. I don’t like an outline. I like ideas to flow forth as I’m writing, then figure out how to make it all work.

What is there about human behavior you find most interesting to explore in such an extreme area—lives violently ended?

Well…human behavior sucks as we know. I think it’s why mysteries are so much fun to read, because we all know someone whose character flaws can lead them to some dastardly ends: greed, jealousy, self-hatred, stupidity. Yada yada yada.

Describe a typical writing day.

When I’m ensconced in a book, I start at about 8 in the morning and write until I have to stop because 8 hours have passed. So, I write until I’m finished. With the short stories, it’s different for some reason. I’ll write for about three hours in the morning and get on with what else I have to do for the day. I have found that not writing is sometimes as important as sitting down and doing it. For me, I have to get out in the world for ideas to start buzzing, while sitting and trying to think of what’s next doesn’t always work.

How did your experiences at The New Yorker, Time-Life, and Random House teach you about editing and thinking about your audience?

I’d like to think my experiences at those places did teach me something about writing, but what I learned was the characters of the people I worked for and with. I don’t think about my audience (perhaps a fatal flaw).

What sort of mischief do you see Annie mixing herself in next?

I’ve started book four of the Annie Fillmore series, so there’s plenty of trouble a foot in that one. There’s endless mischief for Annie, because she expects it, and life is all around.

Are you interested in trying out a new persona for crime-solving?

No, I don’t foresee another persona for crime-solving. I do have a long list of ideas for books that are not crime novels, not entirely anyway.

Any short stories on the horizon?

I am writing short stories now and have sent a few off into the wild blue yonder of the short story publishing world. Some are mystery/crime stories, others are ‘literary’ in scope.

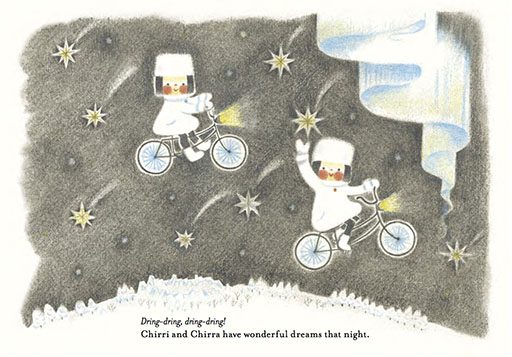

Chirri & Chirra: In the Night

Chirri & Chirra: In the Night

Kaya Doi / David Boyd

Enchanted Lion

The adorable bicycle-riding twins are back. This time, Chirri and Chirra take their bikes on a night-time adventure in which they gain entrance to a party hosted by cats. Beginning with a visit to the bar, they are prepared “full-moon sodas made from black grapes and other goodies,” which transform them into cats. At this point, they are ready for the festival to begin! Then, things get weird (in a welcoming, non-intimidating way). I suppose that some Americans will feel squeamish over the idea of children (ages 3-8) reading about stand-ins for the transformative powers of inebriation, so be warned. (Asians (Doi is Japanese) and Europeans have different notions than Americans about what is appropriate for children.) Otherwise, have fun!

The Traces

The Traces

Mairead Small Staid

Deep Vellum

One young woman’s exploration of the marvels of existence, as recounted through her memories as a student studying art history over one summer in Italy. Dante, Calvino, medieval religion, painting and sculpture, friendship and love are all explored here in a form true to the original meaning of “essay”: To test an idea by taking it through various permutations to discover where it leads. Staid brings to the book an assimilation of years’ worth of thought, supported by her own observations, of course, and those of her professors’ and friends’, too, as well as by readings from Benjamin, John Berger and Vasari, and others. Traces is a young adult’s devotion to understanding the world and her place in it that she will probably spend the rest of her life tearing down and reforming.

Plaza

Plaza

Yokoyama Yuichi / Ryan Holmberg

Living the Line

Plaza’s story is all action, no plot or dialogue, but lots of transliterated onomatopoeia. The setting appears to be something like a conveyor belt set at just above head level. About the width of a suburban side street, the conveyor belt’s length would seem to be infinite. Below it is a scrim of standing audience, humanoid in form but lacking discernable gender difference, with heads/masks/helmets that are spherical with a black cone attached where a nose might be. Depending on the actions occurring on the conveyor belt, the audience either seems to be cheering, beating each other up, or ducking from being struck by a deadly instrument coming from the conveyor belt.

And what is on the conveyor belt? What appears constantly changes, like a parade, but bodies rise, descend, or swoop out of holes in the floor of the conveyor belt, projectiles are shot, explosions occur, long knives are swept across the audience, swinging long knives, and so forth —organized chaos, in other words, in which the challenge the artist set for himself seems to have been to design as many costumes, devices, maneuvers and actions he can with without repeating himself.

Making the busy, chaotic action on the conveyor belt visually denser are lines indicating movement (horizontal, vertical, and spin) and overlain characters indicating onomatopoeia that take up about a third of each panel. In short, Yuichi turns manga into abstract art. Readers who like conventional manga will probably avoid this book. Readers, like me, who are indifferent to manga are likelier to enjoy the chaos.

The book includes an interview with Yuichi translated by Ryan Holmberg about the making of Plaza and Yuichi’s career in general.

Creature: Paintings, Drawings, and Reflections

Creature: Paintings, Drawings, and Reflections

Shaun Tan

Levine Querdo

Shaun Tan writes and illustrates works for children that adults also appreciate. Probably best known in the U.S. (he hails from Australia) as the author of The Arrival (a story of an immigrant’s arrival in a strange new country) or his Academy Award-winning animated short, The Lost Thing. I first read The Arrival soon after my first fourth months living in working in Shanghai, a country whose languages I couldn’t speak or writing I couldn’t read, where different social practices and foods prevailed, and the line between safe and dangerous was ambiguous.

Tan creates environments where the familiar and new or alien meet and the line between safe and dangerous is blurry. Still, enquiring minds (children’s, in particular) want to know, and Tan encourages our curiosity to reveal the rich worlds it reveals and makes available to us. Tan’s Lost Thing, for instance, is not just a creature but also our Virgil, giving us a tour not of Hades but of brave new worlds with such things in them as other Lost Things, and the tour ending with the vanishment of fright.

Creatures collects a wide range of Tan’s encouragers of curiosity that he has created over the years, including on paintings, sketches, and illustrations from a number of his previous publications. It’s large size and print quality do justice to Tan’s work, and several points along the way the pages turn to Tan’s thoughts on creativity and his creatures. To be clear, this is an anthology of illustrations, not a story. As a sampler of his considerable illustration abilities, this is a great book for Tan’s fans as well as for readers who enjoy and appreciate well-wrought works.

The Continental, 1(2): Crave

The Continental, 1(2): Crave

The Continental is a new publication out of Hungary, which aims to provide Central Europe, the U.S., and other places where English is read, with a quarterly publication (and website) representing art, literature, poetry, cultural observations, and political commentary from a predominantly (liberal) Central European point of view, but not limited to Central European interests. Each issues focuses on a different topic—“Cravings” being the idea / sensation explored in this issue, while other issues have considered “Prejudice,” “Faith,” and “Noir.” The notion of “Cravings” doesn’t imply just erotica: “Showdown in L.A.,” by András Dezsö (Thomas Cooper, translator) chronicles a true-crime story about Hungarian mobsters DBA Americans. Poetic justice, I’m happy to report, still occurs, and it’s a beautiful slow burn. There’s an article on a Ukraine zookeeper who cares for the animals brought to the estate of Putin-stooge and former president of Ukraine, Viktor Fedorovych Yanukovych. Of course, there are no national funds for this zoo, which much be funded from cash and food donations, although some of the supplies received end up being sold on the black market by other zookeepers. . . The performance artist Marina Abramovi? is interviewed; the war in Kyiv is reported on first-hand; a Lebanese writer describes the importance of having a room of her own for writing (in a corrupt, war-torn, and impoverished nation, the view out her window is an unmistakable picture of the state of the nation); George Szirtes introduces and contributes to an excellent batch of erotic poems from six writers; and more. I’m glad to see a new international magazine that combines international fiction and poetry with Cabinet-like, surprising nonfiction pieces. Difficult to come by, at present, and sometimes available without having to pay exorbitant postage from Europe to the U.S.

Quantum Listening

Quantum Listening

Pauline Oliveros

Ignota.org

Pauline Oliveros was an American composer and improviser of the latter half of the 20th century, who created pioneering works in electronic music and avant-garde accordion music. Over the decades, she developed a technique for performing and listening to what she called Deep Listening compositions—series of instructions that can be performed by anybody, musician or not, musically literate or not. Deep Listening’s counterpart, Quantum Listening, “is listening in as many ways as possible simultaneously—changing and being changed by the listening.” An active form of meditation in which thought tries to focus—simultaneously—on one’s environment, how others manifest their responses to the environment, and how one responds / participates in listening to how others listen in the available context. Active listening deepens and slows the development of sounds produced due to heightened states of awareness—listening to listening—ultimately culminating in a serenity born of hearing, being heard, and having the flows of sounds and silences balance. The essay is brief—the point is to practice Deep Listening, not talk about it.

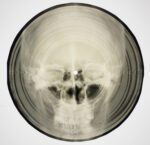

Bone Music: Soviet X-Ray Audio</strong>

Bone Music: Soviet X-Ray Audio</strong>

Stephen Coates

Strange Attractor Press

From roughly 1948 to 1964, enterprising Soviets gained access to forbidden music by listening to tunes carved into x-rays. Each x-ray could hold one song of three- or four-minutes’ duration on one side only. The shallow grooves etched into the x-rays in conjunction with poor-quality needles (often still made of steel for old wind-up gramophones) meant that most recordings could only be played a few times before being scratched beyond use. Of course, many of the songs were banned jazz and pop tunes from the West but, surprisingly enough, most of the x-ray music was of traditional Russian folksongs that had now been banned by Soviet censors.

Bone music’s origins seem to be in Hungary during the 1930s, generated by Sophie Török (a poet and salon hostess) and István Makai (a sound engineer). Makai, in fact, published articles describing how to create records at home with x-rays. The recordings were not illegal, however, and seemed to be an inexpensive way to record and share music and poetry readings. Most of Bone Music includes information on the figures behind the bootleg recording in the Soviet Union—who they were, how they built their equipment, how they ended up arrested, and so forth—along with profuse illustrations of the records themselves and Soviet anti-bone music propaganda.

Overall, a brief and entertaining history of a little-known criminal activity, Soviet style. Comes with instructions for cutting your own x-ray record.

The European Review of Books, Issue 1

The European Review of Books, Issue 1

From the Netherlands comes a new journal of arts, cultural, and politics, The European Review of Books (I contributed to the fundraiser that helped get it off the ground). The print version is in English, but the website has the articles available in the original language, for those who’d like to compare notes. Editorially, it aims to be something of New York Review of Books with a European sensibility and only three times a year.

Highlights from the first issue include an article on how Google and (to a lesser extent) Facebook financially support journalism worldwide while undermining investigations into their own shady, unethical, and/or illegal activities; an essay on the point of keeping material and nonmaterial ephemera from the past (nonmaterial = online); and an interview with an African writer now living in Brussels whose childhood and youth were spent in refugee camps. There’s an article on the history of the public reaction to a woman’s breast found preserved at Pompeii (which is now apparently lost, having been misplaced at some point in its shipment from one museum to another).

An American lesbian writer from the big skies of the U.S. West offers a particularly good analysis of a Russian lesbian writer from the Steppes of Russia, with poetry by the Russian (male) Gennadiy Aygi symbolically mediating between the two women’s experiences. Menachem Kaiser metaphorically wrings his hands over having a story translated into a language he doesn’t understand—not recognizing it when re-translated back into English (like Twain’s story of the jumping frog translated into French then back again into English) and being horrified by what people might make of it.

Floor Koomen’s short and fascinating essay, “Unclaimed, Claimed, and Unclaimable,” is about three tracts of land, one of them imaginary. I provide one spoiler: A bit of desert exists between Egypt and Sudan that neither is willing to claim. And George Blaustein (“A Kayak in Zierikzee: On American discoveries of Europe”) examines the issue of historical epistemology via the research of the controversial historian, the late Jack D. Forbes, in particular, his last book, The American Discovery of Europe (2007) in which Forbes claims—with mixtures of slim but interesting evidence and bold conjectures—that Native Americans came to Europe—on their own accord—centuries before Europeans managed make it to America and return. For Blaustein, the larger picture that Forbes raises questions regarding changing notions of evidence over time, the fact that some historical assessments once dismissed as unlikely are now seen as quite possible or in fact true.

Overall, a promising and interesting new publication.

Novel Explosives

Novel Explosives

Jim Gauer

Zerogram Press

Let’s cut to the chase: This is an excellent book. Buy and copy for yourself and your friends and—assuming you already love novels of ideas—dig in. No rush. It’s 700+ plus pages of pure reading pleasure, but at the rate of (for me, at least) 25 pages an hour—pages replete with full-page and two-and-a-half-page long paragraphs (not really a talky book)—you’ll be pretty much compelled to slow down. And Jim Gauer’s narrative clock does have occasion to slow things down to the femtosecond level (one quadrillionth of a second). Gauer has a lot to say and we, metaphorically speaking, don’t have a lot of time to act on it.

Novel Explosives is a philosophical novel occurring during a recent Easter week, and it explores, in small part, the ongoing rift between reason and sensibility. Identity, responsibility, and redemption are some of the abstract ideas explored, and venture capitalist, physicist, and medical practices and materials provide examples of those ideas. Three narrative strands unite a simple storyline: one is narrated by an amnesiac in unfamiliar settings and little money; the second is narrated by a venture capitalist whose latest start-up has gone disastrously wrong; and the third omniscient narrated about a pair of henchmen for a drug lord who latest assignment is going disastrously wrong.

The novel is largely sited in Ciudad Juarez, currently Hell’s largest branch office in North America, where the forces of reason in the name of capitalism and military efficiency unite, exporting to the world goods their factory workers will never be able to afford and drugs Americans can’t live without. If that sounds like a bummer—it is—I’m way ahead of the story which begins with a curious mystery.

Our narrator wakes up in hotel room in a quaint town called Guanajuato, Guanajuato—a place he has no recollection of. In fact, he has no recollection of anything personal related to himself or his experiences, including his name. He is able, however, to recall facts but not where, how, or why he learned them. When checking his mind for areas of knowledge that seem particularly deep, he finds that he knows much about finance and its regulations; otherwise, he seems to be a reasonably educated soul. One clue to his situation is the “large painful knot, the size of a baseball cut in half, on the back right center of the top of my head.”

The narrator, looking around his hotel room, discovers a wallet with an ID card—apparently his—whose photograph is an 80-year-old picture of the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, and whose name and address are those of one of Pessoa’s heteronyms, Alvaro de Campos, which only further confuses the narrator. Is this supposed to be him? He has only a 1,000-peso note and an ATM card whose PIN number he is unable to determine from among the dozens of other number sequences he discovers he has also memorized.

This is our in medias res. Tying the rest of the threads together concerns the rest of the novel, which—for comparison’s sake—is kind of like inept Elmore Leonard-type crooks meet tested moral principles from Coen Bros. films, as told by David Foster Wallace waxing ironic at length, but with all the footnotes integrated into the body text. But it has its profoundly ugly and serious side too, emphasizing through example the extent to which the average American, myself included, is complicit in the actions described.

That said, there’s a reason this book takes place during Easter week, and that’s the sense of a sacrifice that, after which, will allow others to atone for their own bad behavior. What poetry after Auschwitz, when uncommonly cruel drug lords, who are also big Wall Street investors, can quote Shakespeare? Gauer holds out a sense of potential redemption for us from the so-called better living that was to have come through chemistry—if we stop now, before the bill for fulfilling our wishes at all costs comes due.

Or, put another way, How much do you know about face transplants?

The Failures of Philosophy: A Historical Essay

The Failures of Philosophy: A Historical Essay

Stephen Gaukroger

Princeton University Press

The Failures of Philosophy is an assessment of the current state of philosophy and how it got there by a professor emeritus of history of philosophy and history of science at the University of Sydney, Stephen Gaukroger. Gaukroger’s premise is that Western philosophy—beginning with the Presocratic philosophers who flourished about 500 years before Plato—has had fallow periods, sometimes lasting centuries, during which other practices produced, for Western culture, more useful ideas and changes in behavior than the philosophies of the time were able to, including, alas, today.

Gaukroger sets out to demonstrate when and why these shifts from philosophy occurred and determine the types of tasks and questions philosophy is better positioned to produce than are other fields. More specifically, Gaukroger rejects the assertion that philosophy has enjoyed a steady, 2,500-year-old march of progress and instead posits that philosophy’s history has been discontinuous both over time and as to the types of questions it has set out to solve and been able to solve. The Failures of Philosophy is structured to follow Western philosophy over time and in each chapter address the types of questions philosophy chose to address and how well and poorly the answers it provided succeeded in solving the problems at hand, compared to other methods of the same time.

Philosophy’s original concerns regarded what it meant to be a “happy man” (sic), encompassing what a good life and morality/ethics consisted of, i.e., the components of virtue. Divisions arose among and between Platonists and other philosophical sects that none could solve regarding virtue and concerning the gap between logic’s strict rationalism and morality’s emotional component. The upshot was that a person could be happy but not at all moral, and a person could be virtuous without having knowledge of what being virtuous meant.

In contrast, Ancient Greek drama did better at exploring the gap between emotion and reason and providing satisfactory results than did philosophy, as the ideal requirement of ancient drama was to produce a catharsis in the audience that would move them to change their own assumptions and behaviors.

By the fourth or fifth century A.D., Christian theologians turned to Greek and Roman philosophy as methods that could be applied to providing the rationale for ends already determined by Christian teleology. So rather than a program of asking questions and exploring wherever the answers took them, philosophy became subordinate to theology as a mere tool to provide pathways to outcomes already determined.

However, with the rediscovery of Aristotle in the 13th century came the idea of separating metaphysical questions into those who answers are revealed (theocracy) and those whose answers are found in nature (natural philosophy, which can be tested). Thus, how material phenomenon occurred and acted differed from why or for what purpose it happened. The how could be tested by sciences, the why through abstract reasoning; thus, Thomas Aquinas.

Aquinas paved the way for Descartes, who further explored the divisions in knowledge between experiential and revealed, between sensate and cognitive forms of knowledge. Descartes showed the limits of natural philosophy regarding our ability to know the world and he determined a way for epistemology (the study of how we know what we know) to demonstrate the truth of statements via thought. One result of his insights was “an explanation of how the orbits of planets are formed . . . without invoking mysterious forces which act at a distance through empty space”; that is, his explanation of how the planets move over time did not require him to invoke any metaphysical causes, establishing a rift between theology and science for explanations of material phenomena.

A limitation of Descartes’ other contribution—“I think, therefore I am”—is that it does not account for how we come to interpret visual apperceptions as we do. John Locke proposes that our sense of knowledge develops from experience (sensate) and reason (mental), the general truth of which is demonstrated via evolutionary survival (not the terms Locke used). Furthermore, Locke fruitfully counters Descartes’ notion that thought precedes sensation and demonstrates that sensation forms our basis for what to think about.

Locke’s line of thinking was then further developed by such French philosophers as Diderot, Condillac, and Voltaire:

By the mid-[18th] century, in the work of writers such as Diderot, sensibility/sensitivity/sensation is a unified phenomenon having physiological, moral, and aesthetic dimensions, and it lies at the basis of our relation to the physical: it is what natural understanding has to be premised on.

As history shows, the traditional Platonic approaches to questions of morality fail at negotiating moral ambiguity, cases in which competing parties have morally good goals that are at odds with each other. That is, no Platonic moral system is comprehensive enough to demonstrate that morality is anything other than merely a private matter of personal values. But building a philosophical framework for moral pluralism (i.e., so that morality rises above mere matter of opinion) requires finding a way to ensure that “moral pluralism does not simply degenerate into moral relativism, of the kind traditionally ascribed to the sophists.”

Adam Smith’s idea of moral pluralism sought to prevent self-interest from deteriorating into mere avarice, by pairing “sympathy” with “prudence”:

Prudence, along with justice, humanity, generosity, and public-spiritedness, for example, is a virtue. But sympathy is not a virtue as such. Rather, it provides a criterion by which one judges the appropriateness of behavior.

But in judging the appropriateness of behavior, Jeremy Bentham recognizes that collective, community interests are not necessarily the same as individual interests and may conflict with them. Instead of beginning with the individual for understanding moral correctness, Bentham looks at the consequences of actions rather than the intentions behind him. Hume seeks to bring sensation and reason into harmony.

The failures of Kant and Hegel and their acolytes to devise a totalizing system of philosophy by which all questions could be examined lead to, beginning in Germany during the mid-19th century, the ascent of science as the field that did provide rational, materialist explanations and procedures for deriving even universal ethics to rationally live by. In Britain, John Stewart Mill quantifies morality (thereby making it “scientific”) by emphasizing the consequences of actions rather than intentions. Since establishing a series of actions that produce specific, desired results is an area that the sciences do well, philosophy has ever since been science’s mere handmaiden, acting simply to validate science’s claims.

From philosophy being subsumed by science to Wittgenstein and Heidegger urging a return to pre-philosophical thought, philosophy is now at an impasse, and the questions the sciences are best suited to answering aren’t the only valid questions that need answering. For Gaukroger, conditions are ripe for someone to re-invent philosophy while it otherwise hibernates during the sciences’ current ascendence.