The Feeling Sonnets

The Feeling Sonnets

Eugene Ostashevsky

NYRB Poets

Eugene Ostashevsky—poet, translator and anthologist of modern Russian writers—was born in Leningrad (St. Petersburg now, again) but moved with his parents to the U.S., learning English, one would gather from his own works, based on word play and puns. The word play permeating The Feeling Sonnets exists less to arouse a sense the ironic and more to draw out the multiple meanings a single word may have, depending on context, as well as ancillary semantic echoes in punning homophones. The comedic and tragic live together—the two are inseparable, perhaps unhappily—and yet here they are, Groucho Marx and Gertrude Stein, demonstrating the permutations that even the most basic vocabulary is subject to about the vagaries of life, what poetry tries to do, and fatherhood.

Here are two excerpts from “The Fooling Sonnets,” the first on music, the second on capitalism, world trade, and national heirarchies:

If Errato is the muse of poetry, who is the music of music.

No muse is the muse of music. Any muse is the muse of music.

A muse is she musing about her meaning with music.

Take meaning away from musing and all that remains is music.

It is the music that makes for feeling and not the meaning. . .

A fire took place here, a conflagration.

It’s called a conflagration because it started with flags.

A flag is a mark. If there’s a mark, there’s market.

I come from the market, make dinner, and engage in struggle.

It is a struggle to get my daughters to sleep. They sleep on bunk beds.

The bunks beds are contemporary. They come from Ikea.

There were transported by trucks. My daughters are transported.

There is a herd of unicorns on the rug below them. They come from developing markets.

In markets that are already developed, philosophers say that unicorns do not exist.

There’s only one step from the remarkable to the marketable, and the unicorns have taken it.

So say the people of developing markets. But the philosophers do not hear them.

“Die Screibblockade; or, The Feeding Sonnets,” is dedicated to Polina Barskova, also from Leningrad, and a poet who moved to the U.S. with her parents, a poet to whose Living Pictures Ostashevsky has written an introduction.” The subject of “Die Screibblockade” is ostensibly writer’s block (what the title translates as in English), but in the following passage, Ostashevsky focuses on the linguistic echoes—semantic and phonic—among three European languages, their reverberations throughout modern history:

Die Siege in German is the plural of der Sieg, which means victory.

In French la siege means seat, la chair means flesh, and la fleche means arrow.

Our [i.e., Russian] siege means you pull up a chair and wait for the city to eat through its stores and then starve, achieving victory.

A few other Russian victories include the following items:

Death by fire and especially death by friendly fire.

Death by state security services, because the state is always feeling insecurity that it’s not providing enough services.

Death by rationing, a rational death, when those with less food die so that those with more food may enjoy more food.

Purging the enemy within is a hallmark of every repressive regime, especially those eager to earn bragging rights for the efficiencies of their bureaucratic rationalism in service to the greater ideology.

Eugene Ostashevsky is a sharp, intelligent writer who grasps the perniciousness of systems designed only to perpetuate themselves at the expense of others, and who can do so poetically with the systems’ own words.

Lucky Breaks

Lucky Breaks

Yevgenia Belorusets / Eugene Ostashevsky

New Directions

Yevgenia Belorusets’s Lucky Breaks consists of character sketches of women from Kyiv and Ukraine’s Donbas region, living under the shadow of Russia’s war against Ukraine since 2014. Depictions of everyday lives lived under exceptional circumstances allow inexplicable events (people suddenly go missing) to transform into rational outcomes as a result of that war.

The women hold low-paying, low-skill jobs requiring only a modicum of training and no university degree. Working as hairdressers, running and owning small shops, and other odd jobs, these sorts of “everywomen” don’t usually appear in books about war. The women are often past their prime, either single, widowed, or divorced, and thus usually ignored by the larger society as disposable cogs in a service-oriented economy. And yet: The women in Lucky Breaks are all about that “and yet,” since the women are more than statistical abberations.

Translator Eugene Ostashevsky’s helpful afterword places Belorusets’s work historically, literarily, and linguistically among the divisions and integrations of Ukraine and Russian culture and languages.

Living Pictures

Living Pictures

Polina Barskova / Catherine Ciepilla

NYRB Classics

Polina Barskova was born in raised in St. Petersburg, Russia, formerly Leningrad. Eventually settling in the U.S., where she teaches now teaches at Berkeley, only after she moved out did she discover that a mass grave was the bedrock of a park she and her friends played at while children. The mass grave consisted of the bodies of citizens who died during the blockade of Leningrad, in which food and power supplies to the city were cut off by Soviet authorities (presumably on Lenin’s orders), so that if the city fell to the Nazis, the Nazis wouldn’t gain anything in the way of fuel or food.

Borskova became interested in researching letters and diaries from people forced to endure the blockade. Eugene Ostashevsky tells us, in his introduction to Living Pictures, that during a three-month winter-time period “Leningrad authorities arrested a total of 866 people on charges related to the eating of dead bodies and even to the murder of the living with the intent to eat them. Some of this activity was said to be organized. The overwhelming majority of the accused were refugees from the countryside, largely women.” Thus, many of the letters and diaries cite incidents of cannibalism, and explain how such things could come to be.

Even 70 years years ago, Soviet citizens knew the amateur status of their national military: Numbers made up for what tactics and technology couldn’t. From Barskova’s story “Eastrangement”: “There, over-across the ground, lie those whose brief military exertions—the length of a lightning bug’s life—were deprived of any meaning by the monstrosities of Soviet military unprofessionalism. . .: Some made it a hundred meters, some a little more.”

She also notes how the language of her source material was pared away over time as bodily degradations waxed and bodies waned:

Word by word, declensions conjugations vanishing like lard and sugar in November. Commas and dashed blanch and collapse, stop making sense, can’t breathe and melt away. Exclamation points were the first to die in blockade diaries, superfluous marks like those superfluous people, refugees without ration cards from Luga and Gatchina.

In typical Soviet fashion, the horror of the blockade was then compounded by another debacle, after the war: “in the so-called Leningrad Affair, the local bosses who did prevent the city from being taken were killed in a massive purge as Moscow reasserted control.”

Parallels to today’s Ukraine under attack from Putin’s armies are hard to miss. (At least Ukraine is unlikely to be reduced to Russian-imposed starvation.) One can only sympathize with and admire the sheer tenacity of a besieged populace, attacked by its own government and a formidable foreign military, each as evil as the other.

Some Say Ice

Some Say Ice

Alessandra Sanguinetti

MACK Books

The first photograph I ever saw by Alessandra Sanguinetti was the cover of Cabinet magazine’s Winter 2009-2010—two young girls, tweenish, clutching each other, while looking away from the camera at an approaching storm. It was Cabinet’s “Friendship” issue, and Sanguinetti’s photograph was evidence enough to encourage me to buy the issue. From that, I discovered that the cover photograph came from her collection The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Enigmatic Meaning of Their Dreams, in which Sanuinetti follows the richly imaginative lives of Guille and Belinda, two Argentines we follow from late childhood early adolescence.

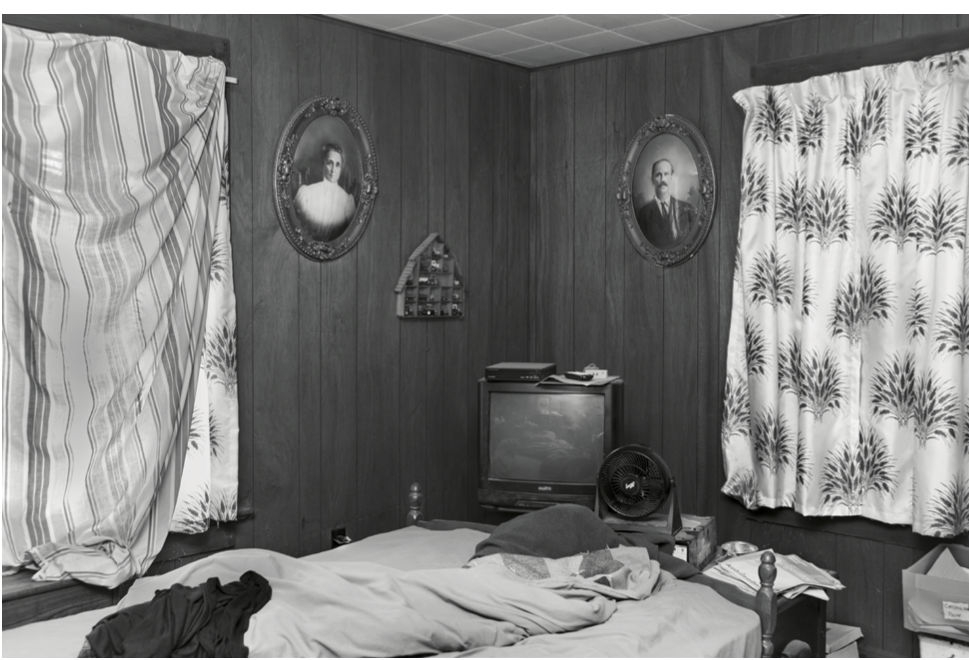

Some Say Ice is Guille and Belinda’s mirror image: B&W photographs of people from small rural towns in Wisconsin, influenced by Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip. Sanguinetti has a great eye and feel for life in isolated places—I’ve been to and lived in places in Michigan much like what she shows here—and Wisconsin seems a far drearier place than the Argentina of Guille and Belinda. Knotty pine paneling; thin, worn carpets; rooms with bad fluorescent lighting; cinderblock, clapboard, and aluminum. Unschooled notions of elegance and fashion, chronic male stolidity, tightly constrained social norms.

With sympathy, insight, and compassion, Alessandra Sanguinetti captures a disquieting sense of place and beauty throughout the book, giving palpable weight to the lives revealed. Some Say Ice is as strong as her earlier work but one that evokes lives of diminished possibilities. The force of life is revealed to greater degree in her photos depicting animals—alive and dead—whose pelts form whirls of designs and energy.

Blue in Green

Blue in Green

Wesley Brown

Blank Forms Editions

Blue in Green begins on a night in August 1959, when Miles Davis, on break between sets at Birdland, is beaten by police, booked, and released. In addition to the humiliation of the attack—hit from behind by a cop he never heard approaching—just weeks after the release of Kind of Blue, is a cauldron of bad feelings: He’s begun beating his wife, Frances Taylor, whom he’s coerced into abandoning her career in ballet and dance, and friends of Davis and Taylor sense something is wrong in the relationship, with Davis as the likely “something”—a man violently jealous in direct proportion to his many insecurities and self-doubts. With few exceptions, Davis trusts almost no one. Coltrane has left his group, Billie Holiday and Lester Young—people he strongly respected and could talk to—recently died, and he’s dealing with his own set of drug problems.

The form of the story is a kind of Odyssey, with Davis driving around Manhattan to cool off after the beating, and Taylor at their apartment, waiting for him to come home. Wesley Brown creates a space to lay out the case of what happened, what preceded it, and what came of it. The sympathy doesn’t mean Brown condones brutal acts against others and self-destructive tendencies. Like Joyce’s Ulysses, Taylor, as Penelope’s stand-in, has the last word, but unlike Joyce’s Ulysses, it ain’t a “yes” for Davis.

Wesley Brown packs a lot of biographical and cultural information into a tidy 65 pages of compulsively readable prose that provides a complex, sympathetic acknowledgement of the psychic forces Davis, Taylor, and other Black artists of the time had to negotiate, compelling them to act as they did.

Mystery Train

Mystery Train

Can Xue / Natascha Bruce

Sublunary Editions

Can Xue, the pen name of Deng Xiaohua, was born in China in 1953, and by the late ’50s her family (Communist Party members) began being persecuted by others within the Party, resulting in years of life and work in “re-education” camps, and ending Deng’s formal education by age 13. Nonetheless, she persisted, and her works have been nominated for prestigious international literature awards, including nominations for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature for her novel The Last Lover, longlisted for the 2019 Booker International Prize for Love in the New Millennium.

Mystery Train is a novella of a long, strange trip whose subtle but persistent sense of Twilight Zone-like disorientation is well-captured in Natascha Bruce’s English rendering. Its mood and its characters’ behaviors put me in mind of Kafka’s Amerika, in which a number of people with vague purposes meet on a trip, form and break alliances, and inhabit a dream-like haze with a logic of its own that is nonetheless easy to follow and convincingly reasonable in the circumstances. In Mystery Train, the protagonist, named Scratch, is a chicken farm hand whose boss has sent him on a trip to buy feed. But the city Scratch is headed to is not on the map, his employer forgot to give him one of the contracts to take to the feed company, and he increasingly feels that he’s been fired with a thousand-yuan severance package.

Love interests are quickly struck up and consummated in this book, amid the train shut down, disappearance (!), forced mountainside camping, successful attacks from wolves, tent burnings, and so forth. But as with the violent chaos, the women Scratch finds himself with are repulsive but sexually satisfying. Ultimately, “He felt sorry for himself, watching as the little door in his heart clicked shut. He didn’t want to be there, probing life’s mysteries with a stinking, birdbrained woman.” The “birdbrained woman” is the butt of abuse for the first two sections, but at this point, for the third section, the story’s point of view is hers, Birdie’s.

If, as Can Xue herself has said, her stories and novels are autobiographies of her interior life, could the mysterious train be a stand-in for Mao’s re-education camps? When Birdie recalls her first days on the train, she remembers an older woman, Belle, scolding her:

“You keep judging people and things according to the standards you had before coming on board, and this isn’t doing you any good. . . The train has severed our links with anywhere outside it, and we have to relearn everything from scratch. I recently started sewing and it’s done wonders for my self-confidence!”

Escaping the unsheltered chaos that the refuge has become is difficult, after the train disappears, since the group is prone to attacks from wolves. Scratch and Birdie, finally manage a way out. As they set to rest, the narrative turns to Birdie, whose tale it becomes in the last third of the book—the tale of a woman whose face was disfigured as a child, resulting in an ugliness so profound the father puts her on the mystery train he has heard about.

What kind of autobiographical life can this possibly represent? What does it mean when something that had the quality of eternity to it—the mystery train—has now disappeared? Well, there’s the sudden wrenching out of one life into another, for reasons out of one’s control. There’s the casual abuse doled out by men against women, presented as just the course of natural events. It was a man who abandoned her as a child; it was a man who put her on the train; it was a man who conducted the train; it was a man who raped her; and it was a man who abandoned her, again, who wanted nothing to do with “a stinking, birdbrained woman.” The train has gone, the men have gone, and Birdie now controls the narrative.

Vivian Maier

Vivian Maier

with essays by Ann Marks and Christa Blümlinger

Thames & Hudson

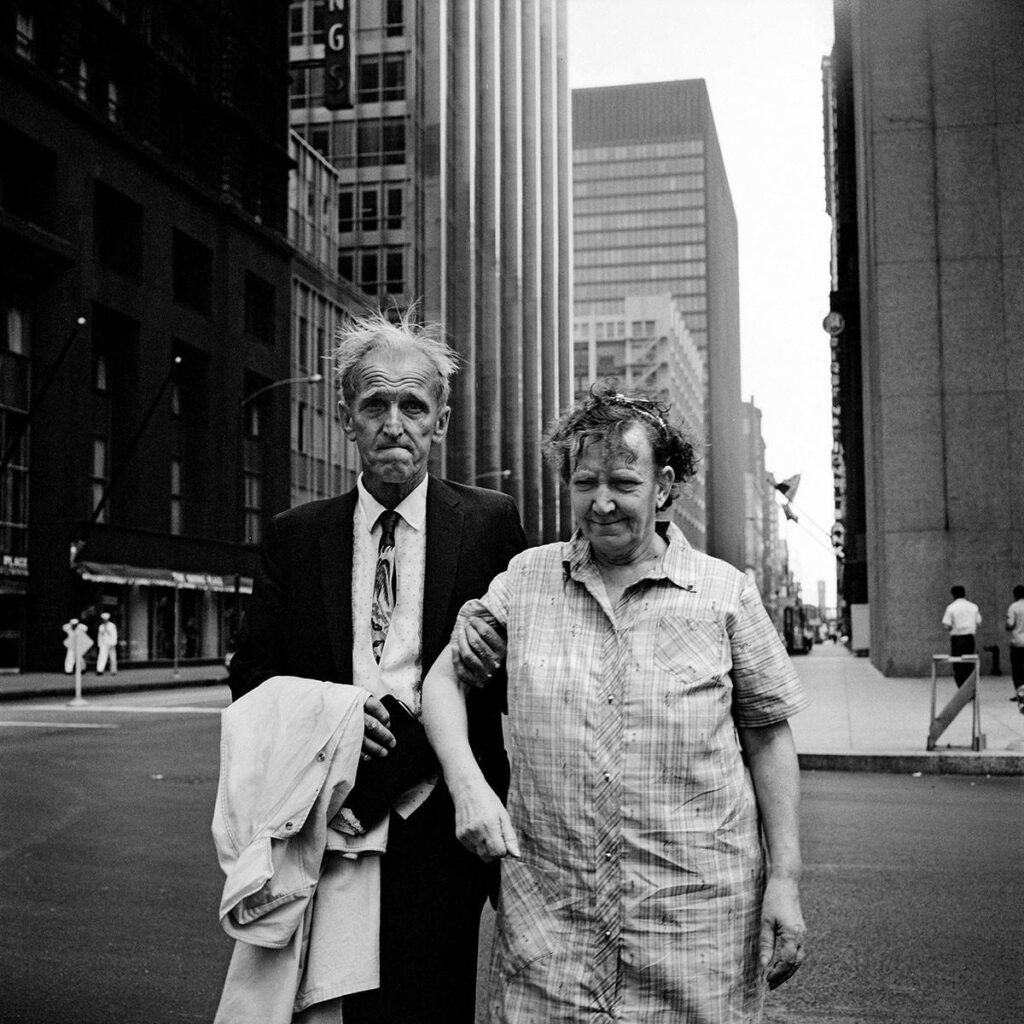

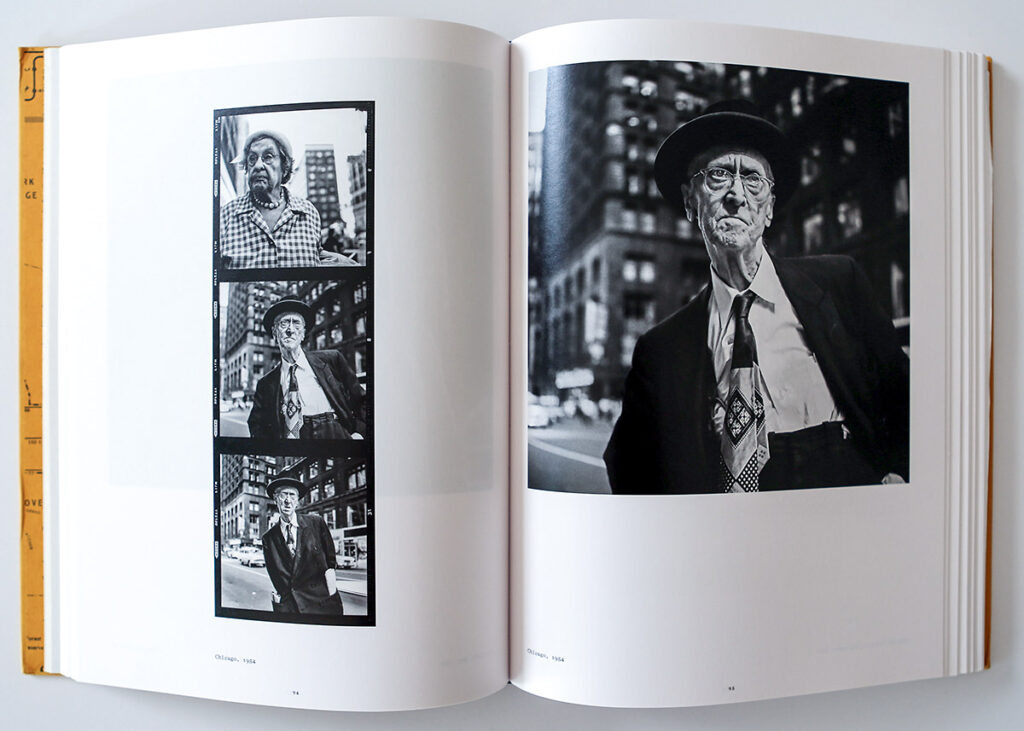

Based on a recent comprehensive exhibit of Vivian Maier’s film and photography in color and black and white, including two analyses of her work by Ann Marks (photography) and Christa Blümlinger (film). By my count, this makes the seventh volume of Maier’s photography to appear in less than 20 years since the discovery of her profound body of work. Each previous collection has weighed in between 200-300 pages, but with a body of works consisting of an estimated 120,00-150,000 images, much has not yet been shown or developed.

Vivian Maier, the book, groups her photography by subject—portraits, self-portraits, street life, gestures, children, patterns, and more. These groupings help highlight the wide range of photographic interests that concerned Maier and the fact that Maier consistently expressed these interests over time. They also show more of her photographs from Europe before she settled into her nanny routine in New York and Chicago.

Blümlinger’s film analysis is particularly helpful and interesting since, as she points out, copyright ownership of Maier’s films has not been established: she left behind no will and some of the films were made as home movies for a family she nannied. Many of the stills have not been published before, so the handful of available clips are welcome, especially in light of Blümlinger’s argument for Maier’s deep familiarity with the avant-garde filmmaking of her time. Maier’s achievement was, at the very least, a triumph of imagination over budget.

Fans of Maier will find lots of new photography to admire, and people new to Maier will find here a collection as good as the others but more comprehensive in its time span and by introducing film as a subject every bit as important to Maier as her photography. As with previous collections of Maier’s work, Vivian Maier left me wondering, “Was she inherently unable to take a bad picture?” What about the 119,000 other shots waiting to be developed?

Ann Marks on the Deep Humanity of Vivian Maier, a Book Dreams Podcast from LitHub.

Love at First Sight

Love at First Sight

Wislawa Szymborska (Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak, trans.) and Beatrice Gasca Queirazza (illustrations)

Seven Stories Press

Wislawa Szymborska, whose poetry won the Nobel Prize in 1996, is remarkable for its simplicity of vocabulary—which favors concrete imagery over abstract concepts—based on seemingly unremarkable domestic activities, stated in a voice that combines gentle prodding and irony with an amiable personality. Which is not to say her poems deal with trifles and superficial emotions. “The Suicide’s Room” from 1995’s View with a Grain of Sand, for instance, is devastating.

Love at First Sight, thankfully, is about suicide’s opposite: A reason to live. Yet, when was that “first sight” that draws couples together? For those couples who have experienced it, Szymborska probes the sense of familiarity and knowing that makes the relationships immediately click into place.

Since they’d never met before, they’re sure

that there’d been nothing between them.

But what’s the word from the streets, staircases, hallways—

perhaps they’ve passed by each other a million times?

I want to ask them

if they don’t remember—

a moment face to face

in some revolving door?

perhaps a “sorry” muttered in a crowd?

a curt “wrong number” caught in the receiver?—

Szymborska’s narrator is sure that the bond a couple experiences at the outset of their romance had an origin, but a repeatable and eternal origin:

Every beginning

is only a sequel, after all,

and the book of events

is always open halfway through.

This notion explains why the people in Beatrice Gasca Queirazza’s illustrations represent a variety of ages: First sight doesn’t have to mean in the blush of youth, and if, due to mortality, one love dies, another love, as rich and enriching as its predecessor, is already in development for the sequel.

Cold Fire

Cold Fire

Verónica Zondek / Katherine Silver

World Poetry Books

“Cold fire” is Chilean poet Verónica Zonek’s term for wind, and Cold Fire is her book-length cycle of 20 cantos devoted to winds. In Canto 1, where we are introduced to the topic, Zonek describes the wind as that which swoops, flutters, pounds, sunders, returns, “departs / twists / snags / thunders” in rage and silence. It’s a polymorphously verbed existence affecting all animate and inanimate objects on land and air, wasting them to nothing, and touching upon one of life’s contradictions: Despite its seeming purposelessness, life teems ardently for existence:

Life and death

eager

so eager

and nothing.

. . .

There’s a wind that needs the earth to work.

There’s an earth that needs the wind to sprout.

There’s an earth that needs the wind and lends its ears to its need.

There’s an earth that sustains us in spite of us.

There’s a wind that speaks for us

and nothing. (from Canto 8)

The wind gives rise to, shapes, and wastes entire environments. The wind in its many moods and iterations can be languidly caressing or brutally exuberant, as in this passage, in which the wind’s rush and speed is conveyed by the authorial stuttering of the conjunction “and,” as if the wind’s speed outpaces the narrator’s ability to describe it:

The snow arrives/ and falls/ falls/ falls mutely/ and covers/ covers albino the fever of the earth/ its delirium/ its bewildered ants/ its critters/ its ardor/ its ground/ and buried is malice/ the red lie/ and quiets/ quiets winter/ and the now faded remains grow quiet/ and the sun rests for a while/ and hides out of sight/ and/ and/ and/ and gone are the seasons/ dormant under smoke/ and/ and/ and/ and gone are birds who sing/ and/ and gone is the break of dawn/ as if eternity had sat down forever at the table/ a parishioner upon defiled/ sullied ground/ wrapped in ash paper (Canto 17)

The history of the world is in the wind, to which the narrator implores us, in Cato 20, to

let the silver fingers of the windgust touch you . . . for my letter on the page sleeps while it waits for the slow roar of awakening . . . for our duty is to read/ and reread/ and pay heed/ even if we are only blood/ and bone/ and dream/ in this long/ long and slow bog.

A beautiful and enchanting work.

One Day in the Secret Forest of Words

One Day in the Secret Forest of Words

Vincente Valero / Richard Sturges

Quantum Prose

Nature poetry reminiscent of Thoreau and Emerson in its meditative qualities but with more emphasis on the physical affecting the spiritual. Born in 1963, on Ibiza, Spain, Vincente Valero’s One Day in the Secret Forest of Words won the International Poetry Prize from the Loewe Foundation in 2007. Comprised of three sections—“Poems,” “Commentaries,” and “Discourse in Verse”—each set of prose poems circles around the same themes, each iteration delving into more detail.

The conceit of the poems is that all of nature represents words and languages as varied as species of lifeforms. Those words and languages require listening and watching, through which understanding will intuitively emerge. The last lines of “Discourse in Verse” nicely summarize the cumulative force and beauty of this book:

. . . At times

in this brightness

full of insects and resin

a bird flies through

the solitude of the written forest. Nobody

could decipher it,

but in its incandescent flight

there are promises that are as thorns of gold,

colored wounds. Beyond that

only the air of the longed-for music of day,

transparent seeds,

the inexhaustible substance of our forest,

the diaphanous secret

of her exhalations.

The suggestion here is that we’re also dealing with a real forest, not an idealized one. Beauty and danger are inseparable: “thorns of gold, / colored wounds,” attractions—“promises”—worth the peril: access to the forest, “the inexhaustible substance.” Ultimately, Valero sees in nature something transcending a mere battle for existence—a dignity in life granted by hope. The following lines, XIX of “Commentaries” (compare to XIX of “Poems”) seems an apt to end the review on—both as another example and as a beautiful invocation to the approaching winter:

It is known that amongst all the beings of the forest the December sun is the one that evokes the most pity, that appears the most forsaken.

He is not even that easy to come across.

Doubtless he feels the cold and hunger, and on his dripping body are to be seen the marks or wounds of extinguished auroras, celestial lacerations.

That is why, when I saw him one day amidst the old branches of an oak tree, trembling and alone, with his eyes tightly closed, I told him to come along with me.

That is why I also opened the door of my house to him.

Richard Sturgess does an excellent job of rendering Valero’s poetry into euphonious, idiomatic English that sounds very much at home.

Other People’s Beds

Other People’s Beds

Anna Punsoda / Mara Faye Letham

Fum d’Estampa Press

Claustre, the narrator of Anna Punsoda’s debut novel, Other People’s Beds, tells of her life as the daughter of a father who drinks himself to death, a mother clingy and ineffectual, and extended family and friends who have no idea how to handle an anxious girl who, beginning in adolescence, takes to cutting, anorexia, vomiting, and heroic doses of laxatives to have some measure of control over her life.

A social outcast from early childhood, she knows it is better to be ignored than to be publicly identified as a loser. Even recess is an unduly awful hazing ritual:

Whatever we were playing, when the two popular girls chose their teams, I was always the last one picked and got stuck into whichever group had fewer people. To even them out, they would say. Dead weight, they meant. I stopped playing because I was afraid of being the last one picked and everyone seeing. I wasn’t embarrassed that nobody wanted me. I was embarrassed that everyone saw. That they would tell other people. And that those people would tell other people. That in the end I wouldn’t be able to leave the house without everyone knowing that I was dimwitted and alone and an outcast.

Although this slim novel is not marketed as a roman à clef, Punsoda provides so many intimate details for Claustre and with such insight into her moods and behaviors as to transcend mere empathy, especially once Claustre enters adolescence and develops eating disorders.

At her father’s funeral, when she asks a woman at the funeral she doesn’t recognize how she knew her father, the woman inadvertently reveals to Claustre that her father had multiple lovers met at a jazz club: “It’s a music club, don’t get the wrong idea,” she said. “But sometimes I go there with two or three of my entertainer friends. The last time I saw him [Claustre’s father] we argued because he was sitting on a sofa with Marisol. He did it to hurt me. . . He always does the most hurtful things.”

Confronting and grappling with the conditions that shaped her into a self-destructive force and unreliable lover comprise the last third of the book, demonstrating why, for so many people, “rehabilitation” is a state in which they live the rest of their lives.

A Ghost Story for Christmas: The Dead and the Countess, The Corner Shop, and A Visit

A Ghost Story for Christmas: The Dead and the Countess, The Corner Shop, and A Visit

Gertrude Atherton, Lady Asquith, Shirley Jackson/ Seth (design and decorations)

Biblioasis

Now up to around two dozen titles, A Ghost Story for Christmas is an annual series of short stories by American and British writers from the late-19th to mid-20th centuries, “designed and decorated” by the totally aces illustrator Seth. Many of the stories were originally published in popular magazines as part of a now gone but once long-standing fashion for relating ghost stories at Christmas. If that seems surprisingly strange, Tim Burton’s film A Nightmare before Christmas seems to have tapped into that mood, and it’s not uncommon for people to describe Halloween as their holiday of choice over Christmas. So, read these palm-sized books—aloud, under a blanket with a flashlight—with that in mind. Seth’s “decorations” convey mood rather than event, maintaining the tensions that fill these tales. (Bonus points for design: Each story begins on page 13.)

This year’s batch of tales includes The Dead and the Countess by Gertrude Atherton, The Corner Shop by Lady Asquith, and A Visit by Shirley Jackson.

The Dead and the Countess is about small, simple parish town one day finds a railway running through it. The trains that rush through twice a day disturb the dead in the local cemetery, and the local priest takes it upon himself to find a solution that will calm their souls.

For taking advantage of a trio of sellers who did not realize what they had, The Corner Shop by Lady Asquith retails an account of atonement and reparation of an antiques dealer. (As if!) These sorts of matters, of course, require help from beyond the grave.

The longest of the tales, A Visit, by Shirley Jackson, is a subtler tale of the eerie, one in which the protagonist, Margaret—on summer vacation with her school friend, Carla—slowly becomes enmeshed in the weird world of an extended family who live in a mansion complete with a tower. Only one character, a friend of Carla’s brother, referred to only as “the captain,” seems to understand what is going on, but the clues he draws to Margaret’s attention are as indirect as his affection for her.

Dry Hole

Dry Hole

David Thomson

Archive of Modern Conflict

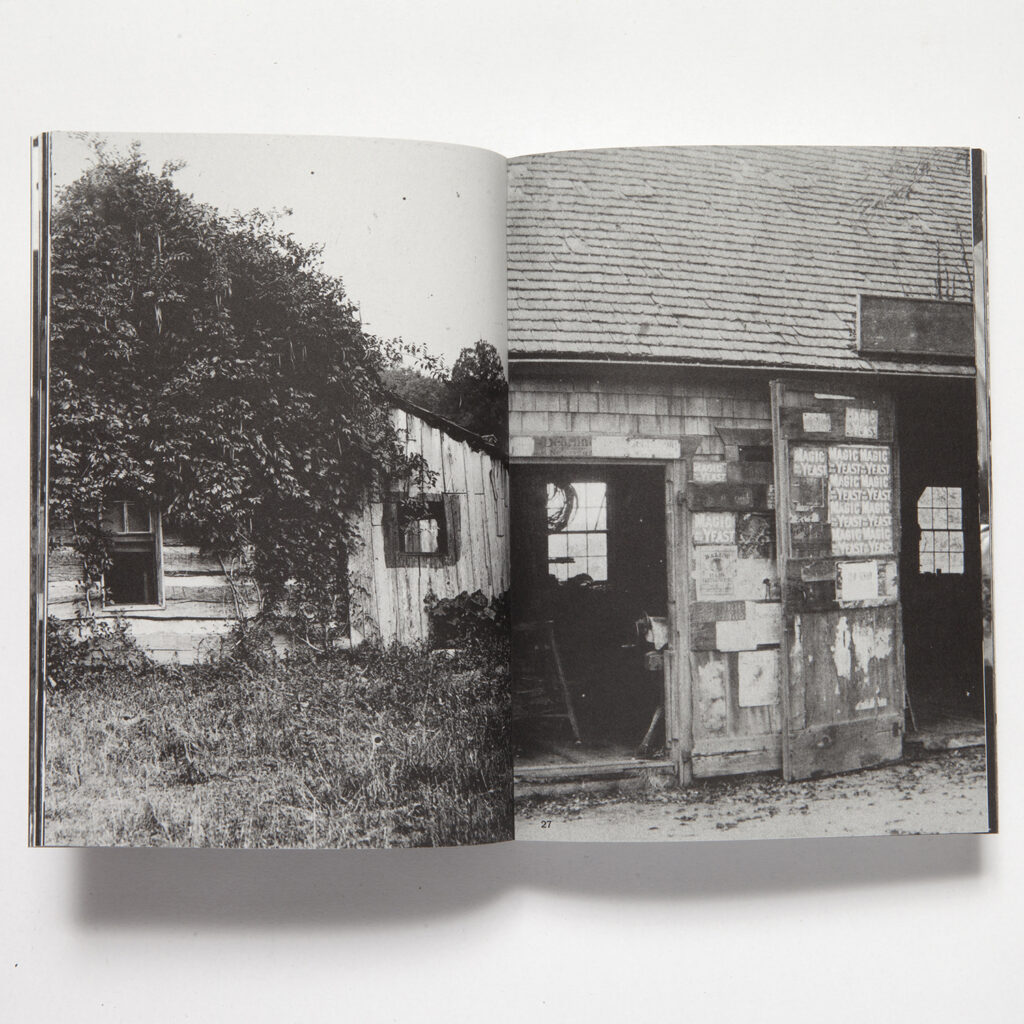

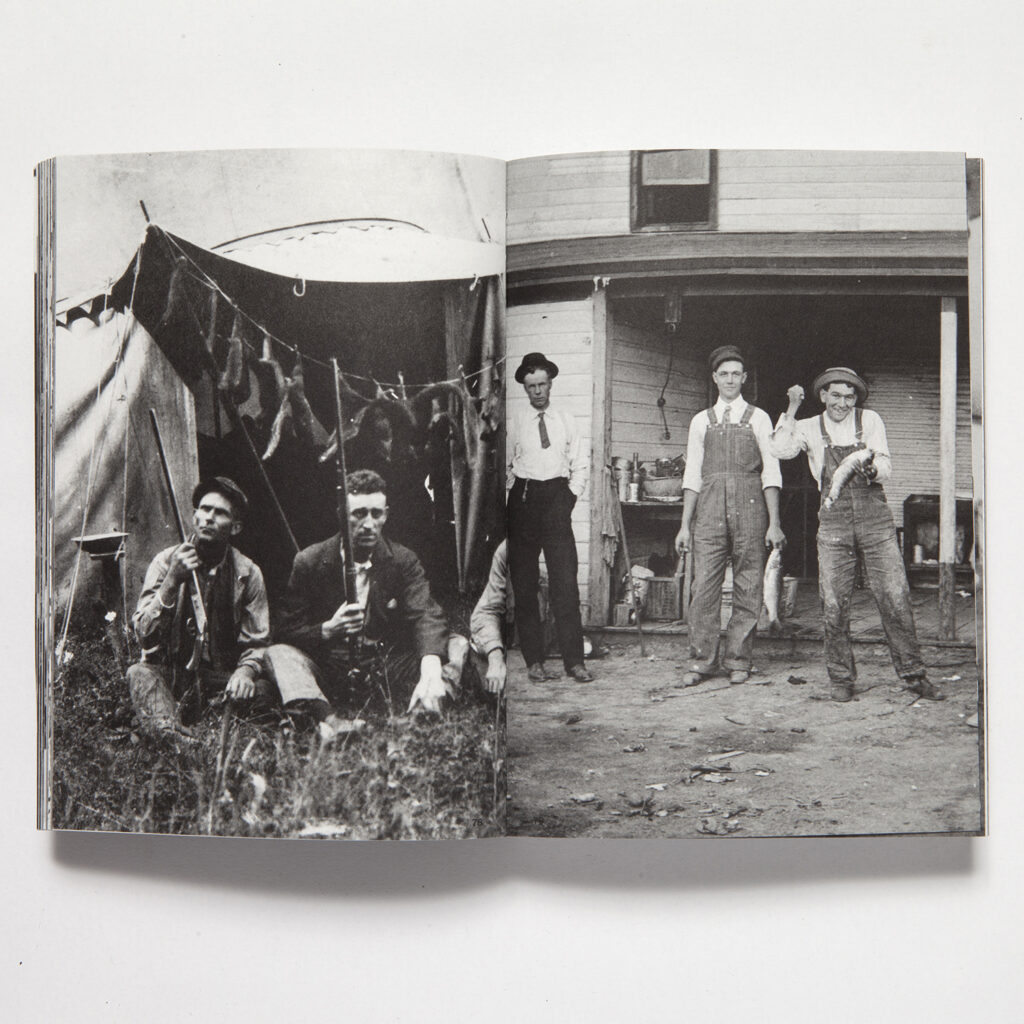

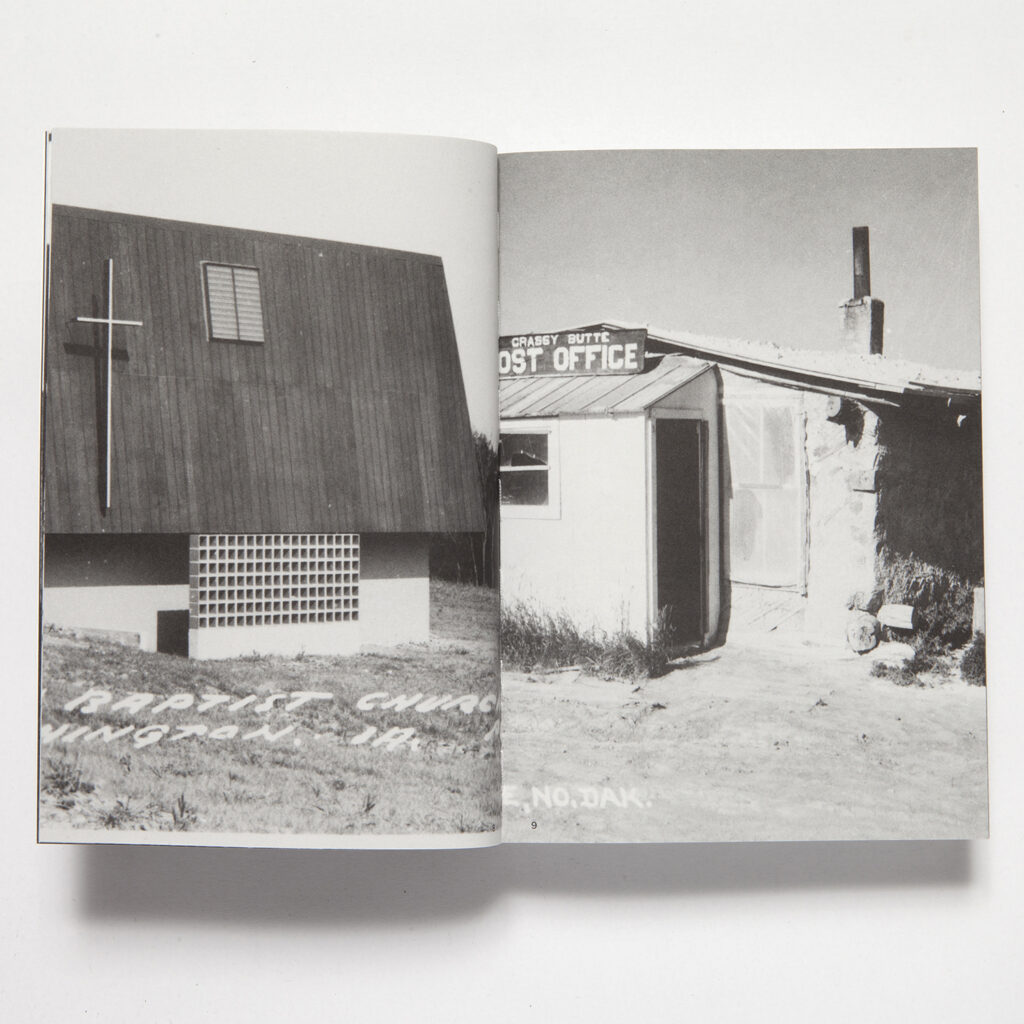

For about 50 years—from around 1900 to 1950—Americans were able to photograph their whereabouts and mail the pictures as postcards. Known as Real Photo Postcards (RPPCs) they were made with small, inexpensive cameras designed for the purpose of sending pictures through the mail, which was cheaper than sending letters. David Thomson is a Canadian collector with a passion for art and photography. Dry Hole is a follow-up to his book “82”. Both books are based on collections of vernacular images. Those in “82” are from World War II soldiers’ photo albums and, in Dry Hole, they are amateur photo postcards.

David Thomson presents, in Dry Hole, 444 images from the RPPC archives (include some taken outside of the U.S.) representing small towns, small businesses, rural livelihoods, education, physical and industrial labor, domestic scenes—tough lives in which everything was done by hand are just a couple of generations removed from now. Thomson has cropped and juxtaposed these images to heighten their energy and drama, exacerbated by the pictures bleeding off the pages—no negative space here. Arranged vaguely by theme and intuition Dry Hole provides a comprehensive if deliberately unsystematic view of everyday life for most Americans about a century ago.

I Will Not Come

I Will Not Come

Arnaud Rykner / Sue Boswell

Snuggly Books

I Will Not Come is a novella about a man who suddenly finds himself visited by angels in his bedroom. Singly or by the thousands, they speak (or, more commonly, scream) without opening their mouths, caress or chew his body, and so forth. It turns out that the visits began by mistake, but the narrator pleads with them not to leave, and so they keep returning.

The angels come and go in a variety of shapes and sizes, sometimes playing hopscotch with the local children, sometimes taking the narrator on long walks through town. He eventually asks them to just leave, which they do. He regrets his request and writes a series of letters to one of the angels, as if to a lost lover whose affections he wrongfully denied, asking the angel to give him just a little more time to tell his friends about his impending departure before rejoining the angel. If he can’t see his angel again in life, he will in death.

Osebol: Voices from a Swedish Village

Osebol: Voices from a Swedish Village

Marit Kapla / Peter Graves

Allan Lane

Osebol is a small, river-side town in the middle of Sweden amid forests. The town’s industries used to be timber cutting and chipboard manufacturing, but over the decades the industries have died, jobs and people moved elsewhere, and the few children whose parent’s live there must be sent to other cities for their education. Several years ago, Marit Kapla interviewed the handful of people who still live in Osebol, who recount their lives in this little place. The words comprising Osebol are the citizens’ own, but Kapla has poetized them, breaking their sentences into lines forming short stanzas, creating a sense of paring language and image to their foundations—a technique I imagine matching Swedish terseness.

Osebol is what one might call a quiet book—the lives and actions described here are unassuming but of huge significance for those persons enmeshed in them. The people and their temperaments remain constant, but technologies do not, affecting the people, their relationships to each other, and the possibilities available to those who don’t ask for much to begin with. Couples meet, marry, and work here (or used to). One townsman, Åke Axelsson (b. 1947), recalls when his wife, Annika (b. 1959), developed cancer, which he manages to see as higher type of good:

But it was good, too

in that it reminded me

I still loved her.

I’d forgotten that.

That’s how things are.

If everything

is just good, good, good

in the end you stop remembering

how good your life is.

It does you good sometimes

to get a slap in the face

so you wake up and realise

just how bloody good your life is.

The book’s chapters are divided by speaker, with each person’s name listed at the bottom of the page, along with birth and sometimes death dates. Above is their testimony, one incident per page. Osebol’s emotional effect is cumulative rather than specific to key incidents in the town’s history, including WWII and the loss of industry. The place and people are one, and our understanding of both comes as we read the stories and facts that span decades, families, couples, and individuals: multiple points of view from multiple points in time.

Here’s Lars Jörlén (1946-2021) on Osebol’s sense of community as an extension of love, caring, and responsibility:

We had some pupils

we went and fetched in the morning.

Their parents couldn’t get them to go to school.

It wasn’t our job

but people took it on.

We took the view

or tried to take it

that all children are everyone’s children.

Even if they have parents of their own

they are still the children of society as a whole.

I think

that’s a good basic outlook.

The economic loss to Osebol over the decades from changes in manufacturing processes has not affected everyone equally, however. As Jörlén goes on to note,

Segregation is extremely marked.

Those who own the forest

and have money

usually grandparents on the mother’s or father’s side

obviously their kid

needs a scooter.

So they go and buy one, cash down

pull out their fat wallet

and count out twenty-five, thirty . . .

It costs forty-five

Right, OK . . .

thousand.

And off they go home

with a scooter or quadbike

while the rest just stand and watch.

The class divisions I encountered

when I came here were enormous.

Most of the townspeople offer assessments more generous than that—at least for the record, as here. There are accounts by refugees from WWII who came here, liked it, and stayed. Anything less than a 100 years’ residency marks in Osebol a person as alien—but generally accepted, and the “outsiders” are still able to enjoy their lives untroubled by xenophobes, and appreciate the Osebol families that took them in.

Nothing sentimental is expressed by this book or Osebol’s town folk. It forms a steady, sympathetic gaze at what has been lost and at what expense. Neo-liberal capitalism probably only accelerated Osebol’s decline. (Trees felled in the surrounding forests are sent overseas for processing, where the work can be done less expensively than at home.) Expressed here are experiences and emotions that are no doubt emerging in other isolated parts of the industrialized First World where populations are aging and declining.

I walk up to a viewpoint.

There’s a rock there

I sit on

and give my dog Grace

a biscuit.

I’ve been there in all kinds of situations.

When I’m in a good mood.

When I’m angry.

When I’m sad and weepy.

When I’ve been really ill.

I want to look out over the whole valley.

The Klarälven river.

In the snow.

I’ve sat up there in the snow.