Kelsey Ronan’s debut novel Chevy in the Hole, is a mixture of fictional and personal histories. Situated in Flint, Michigan, her subject matter crosses family, faith, work, love, and redemption in the midwest. Ronan has received praise from the New York Times and others. Publisher’s Weekly wrote, “Ronan ably humanizes a city known for the pity it’s elicited for many decades.” In an East Village Magazine interview, Ronan spoke about her writing; “It was just like thinking on the page and felt like a spiritually healing thing — reckoning with my family and with grief.” The comments below were given during the Grosse Pointe Public Library Books on the Lake program, held May 7, 2022.

Thank you to Kelsey Ronan for generously sharing your notes and comments. Thanks also to the Grosse Pointe Public Libraries and the Grosse Pointe Library Foundation for their unwavering support of authors, books, and community.

Autographed copies of Chevy in the Hole are available at Book Beat or by mail order in our online gallery.

Thanks so much for having me. This is my first Books on the Lake so I hope it’s not disrespectful of me to start this event talking about how much I love another library.

Last summer, I taught a creative writing class intensive for teens at the Flint Public Library. The group is called the Flint Young Writers Forum and it’s been around forever. I came with my tote bag full of poems by Danez Smith and Jonah Mixon Webber, pencils and notebooks, eager as hell to be leading it for the first time. I’d been a member all through junior high and high school, and since The Flint Public Library was currently undergoing an extensive renovation, for the last year it’s been moved to an interim location, spread out across a string of disused retail stores in a mostly dead mall on the east side called Courtland Center. Fiction is across from the Bath & Body Works. Genealogy and Flint history are in the old Footlocker. At the end of the wing, Flint’s history museum has taken up temporary residence in the old Sears, and you can walk through the fleet of old Chevrolets and Buicks while remembering the agonies of shopping the clearance rack for school clothes with your mom. Everywhere, a ghost. And in the middle of it all, in a space where once someone did ear piercings, there’s a mockup of the library that will be opening in the future, bright white like a spaceship, faceless figures of people dotted over the open floor plan.

It’s been twenty years since I was walking from my high school, now closed—not for renovations, but for population loss and disinvestment– to the Flint Public Library to sit around the table at the Flint Young Writers. Even in the weirdness of this mall location, settling at the table with these writers was something comfortingly familiar. They wrote about crushes and learning to drive and ghosts and family stories and coney islands. They bent into their notebooks, had to be coaxed to read, voices first quavering and then growing steady, bolstered by laughter and little gasps and snaps, by appreciative Mmms.

I’m tempted to say something overly familiar and too glib here about how time passes. Like, the more things change, the more they stay the same. Or, you can take the girl out of Flint but you can’t take Flint out of the girl. Or maybe there’s no stepping into the same Flint River twice. When I was a member of the Flint Young Writer’s Forum, we met every other week at the library’s main campus, a big mid-century structure built in the heyday of Generous Motors, with massive reading room windows looking out on the lawn. A young librarian, Renee, led us in exercises in poetry and prose. We went next door to the Flint Institute of Arts and the green Jell-o dome of the planetarium. In summer we went outside and stretched out under the trees. Once, Renee took us on a magic Saturday trip up to the Theodore Roethke house in Saginaw where we wrote poetry in his old studio.

I’d grown up in a family of readers and storytellers who made time for art after they punched out. They were GM shop rats and bus drivers and roofers. They had well-worn library cards and unfinished novels stashed in drawers and loved a devastating quip at the dinner table. I was a Flint Public Library regular from childhood. First I knew the guinea pigs who lived in the children’s section. By first grade, my mom took out hefty coffee table art history books to acquaint us with the old masters. By middle school, I checked out all the CDs, deep into 60s art rock and jazz, ripping them onto our family PC. I savored books I sort of understood, underlining the words I didn’t know and trying to figure out French phrases with a bilingual dictionary. I dragged a copy of Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure around the house the summer I was 14 and it felt like my brain opened up wider.

But the Flint Young Writers Forum was the first place I got to talk about myself as a writer. I was no longer a bookwormy, precocious kid. I was a writer. It was thrilling, writing and having an adult talk to me. Reading my work aloud. Getting feedback. I got there early and talked about books with Renee the librarian. I distinctly recall the afternoon I told her I’d pulled down my mom’s copy of DH Lawrence Lady Chatterley’s Lover and how cringe I found the euphemisms. “Mound of Venus,” I repeated to her in disgust, all of fourteen years old, virginal and chubby and acned, not totally sure why she was doubling up in laughter.

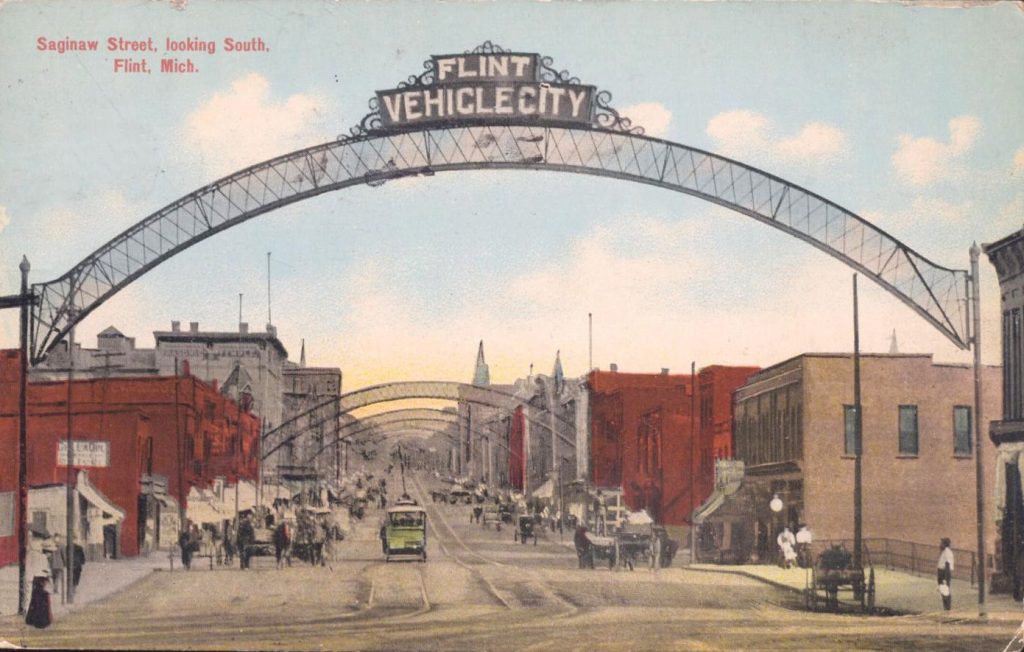

Around this age, too, I was starting to learn how strange Flint was. I was born in the late 80s, the beginning of the Michael Moore era of Flint. The end of GM factory town. Mass unemployment and population loss, the decay that had started with white flight accelerating through deindustrialization. My grandfather, retired from the line, used to drive me around and point out where things used to be. He’d moved from Detroit to Flint as a kid, poor Irish Catholic crowded into rentals in a neighborhood inevitably knocked out for the expressway. In his Flint, you hopped on your bike, pedaled up Saginaw Street to the Ivanhoe to wash dishes with your buddy Jimmy Lum. On Friday nights the movie theaters and dance clubs were full. He pointed out all the ghosts. The residue of previous times. The absences. I learned that there was his Flint and my Flint and all the Flints between.

It’s strange to me that a place as fascinating as Flint, as rich with contradictions, where the fleeting dream of the American middle class collides with foundational injustices and the shortcomings of capitalism, appears so seldom in literature. I was hungry for Flint stories. Beyond the children’s books of Christopher Paul Curtis, like Bud Not Buddy and The Watsons Go to Birmingham, which I love, there’s little I’ve found. As a teenager, when I first encountered Flint in a novel it was on fire in Jeffrey Eugenides’ multigenerational epic Middlesex. “When a Greek Orthodox church in Flint burned down, Milton drove up and salvaged one of the surviving stained-glass windows.”

None of Toni Morrison’s novels are set in Flint, but the city reappears with a tone of dread. Always someone’s moved to Flint and regrets it. Toward the end of Song of Solomon, which takes place in an unnamed Michigan town, Milkman gets a ride from a man who says he has an aunt who moved to Flint. “What kinda place is it, Flint?” Milkman asks. The answer: “Jive. No place you’d want to go to.” From Sula, “Pearl married at fourteen and moved to Flint, Michigan from where she posted frail letters to her mother with two dollars folded into the writing paper.”

I found traces of Flint in other works of fiction, about the working class, about systemic and environmental racism, big multigenerational family sagas, about the aches of belonging to a place that isn’t always able to love you back. Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things is one of those books for me. Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing. Angela Flournoy’s The Turner House. Steinbeck’s East of Eden. Of course, and not even because we’re in Grosse Pointe, Middlesex. But I always wanted that big Flint book that wasn’t just an outrageous headline–The Most Dangerous City in America, The Most Miserable, Murder City USA—with a gallery of ruin porn. I wanted the city’s history, flaws and all, everything it had been through, every shame it has to carry, every triumph, every feat of determination.

When I started writing Chevy in the Hole, I was far from home, homesick and angry. I’d left Flint when I was 25, after my first partner died by heroin overdose. Just a few years later, it was 2016, and the water crisis had just named the horror I already knew. You already know this story. Flint, stripped of democratic agency and left in the control of a state-appointed emergency financial manager, had ended its relationship with Detroit and started pulling drinking water from the Flint River. The citizens, my mom included, knew the river that wound through the old Chevy and Buick complexes, full of industrial run off and old cars, was nothing you wanted to drink. But still the water came, strangely thick, in shifting yellows and browns. They told each other their stories—their rashes, their hair falling out, my mother with her worsening asthma—but the state repeated it was all fine, all okay, till enough people came forward to bear witness. The children of Flint were lead poisoned, pediatrician Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha said. Women were miscarrying and babies weren’t developing, women said. When the state of emergency was declared, rumors circulated that everyone was going to be evacuated. In a city where there wasn’t enough money to keep the streetlights on, where thousands of empty houses sat rotting through the decades, the government wouldn’t possibly replace miles and miles of pipes. After being called a ghost town for years, Flint would finally be vacated by force. This city I loved, that infuriated me, where I’d learned how to tell a story and learned how multiple stories could hold true in one place, where what was true for me and what was true for the person across town could be contradictory and yet equally correct, where I’d had my heart broken, I would lose all of it.

So I began with my family’s story, what I knew and didn’t. As in the book, my great grandparents moved from Detroit to Flint in the depression, my great grandfather selling pots and pans door to door, my great grandmother harboring the secret of her eldest child, who belonged to another man.

In the book, I could access these relatives who died before I was born, and I could live out the moments in Flint’s history that played out long before before I was stretched out on the lawn of the Flint Public Library writing poems—the civil rights protests that reverberated up from Detroit in the summer of ’67, rallied by Flint’s first Black mayor; the music scene when Flint had a quarter of a million people and sat just an hour up I-75, where jazz musicians and Motown acts and rock bands came through and Keith Moon drove a Cadillac into the Holiday Inn swimming pool; the ill-fated theme park AutoWorld that was supposed to shift Flint from factory town to tourist attraction.

This book was a grief project and a love letter. A means of reckoning with those many Flints. What I knew and didn’t.

***

Writing a book is, of course, difficult. There are all those quotes I could trot out here. Like Hemingway’s “There is nothing to writing. You simply sit down at a typewriter, open your veins, and bleed.” Publishing is difficult, too, if you are not someone with connections, as I am not. I spent years writing and rewriting this book, and I faced many rejections.

What kept me writing was what I knew from reading: the thrill of finding something you identify with, of expressing something that feels exactly true. I wanted to write a book that spoke to people in Flint and Detroit that way. Not a sugar coating, not a say nice things about Flint, but a love letter in the way that you understand love as you get older. Not just the things that are lovely and pretty, but the flaws, too. The failings. Not just falling in love, but the work of choosing to love when you’re disappointed, when you feel you’ve been betrayed, when you know some things will never be quite what you hoped for.

There’s that James Joyce quote that’s repeated too much, or at least repeated too much by me in every fiction workshop I facilitate. Joyce said about his book Ulysses, “If one day Dublin suddenly disappeared from the Earth it could be reconstructed out of this book.” At my loftiest, that’s what I wanted Chevy in the Hole to do. The full sweep of the city and its history, from the library lawn to the weirdness of a mostly abandoned mall now full of books, the people growing and building new things in the places where once there was something else.

YOU are one of the best story tellers in our Family. I could listen or read about Flint thru you ? all day.

Only a couple of us will get the ? part, lol. Love you and your book.

I can’t wait to read your book, Kelsey. I grew up a mile away from the shop, and my uncle was part of the strike there in the 1930’s. He lived on Becker St, close enough to walk to work, and his wife told about carrying food over to the men who had locked themselves inside. I wrote this poem 14 years ago.

Field of Broken Dreams

The Chevrolet plant on Chevrolet Avenue,

one mile long that sweeps down, down,

one long mile without a break

save for the railroads cutting through

carrying parts for the thousand-man crew

to screw on, weld on, pound on

to the thousand cars moving slowly down the line

inside those acres of buildings,

windows still broken from the strike of ’36.

I remember the thousand men, mostly men,

streaming out at the end of their shift,

midafternoon,

trudging up the hill,

tired at shift’s end,

wool hats with ear flaps

pulled down against the winter wind.

Pushing against the tide another thousand going in.

I remember the hustle, quick step, frosty breath

hanging in the cold grey air.

The long avenue sweeps down now

buildings smashed to death

by a wrecking ball and wrecking crew.

And now the river is in view.

And in the autumn sun it gleams.

And I see a quiet field of feverfew

and wonder:

Why is the avenue still called Chevrolet

instead of Field of Broken Dreams.

Are there book club discussion questions for this book? Also is there a real place the Frontier Farm is based on? It seems I remember reading about something like that.

From Flint, born in the 70s

Grandpa was a sitdowner

Family was and some still are GM workers