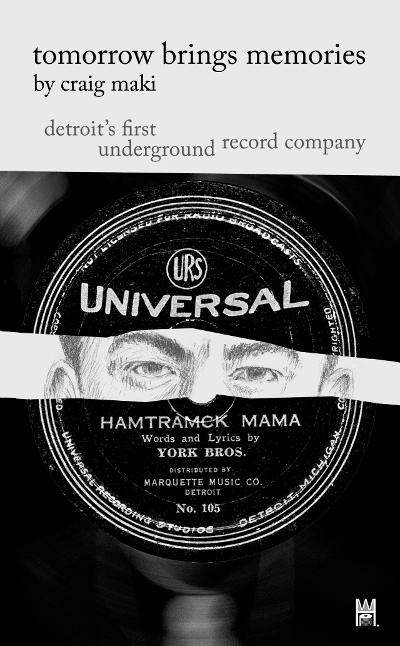

Craig Maki’s recent book: Tomorrow Brings Memories: Detroit’s First Underground Record Company, is a unique and important history uncovering Detroit’s first independent recording studios, artists, and labels of the 1930s and early 1940s.

Craig Maki’s recent book: Tomorrow Brings Memories: Detroit’s First Underground Record Company, is a unique and important history uncovering Detroit’s first independent recording studios, artists, and labels of the 1930s and early 1940s.

Tomorrow Brings Memories reads like a noir mystery; a puzzle-box of interconnected entrepreneurs, genius engineers, artists, mobsters, and conmen. Maki does a great job bringing to life the characters and landscape of the growing scene. The book is filled with reproductions of record labels, photos, and Maki’s original pencil-sketched portraits bring out a quirky “eye-witness” account to the era, like forensic crime drawings.

A central piece of the book revolves around the York Brothers smash hit Hamtramck Mama, recorded for Universal in 1939, which reportedly sold over 300,000 copies in the Detroit area—a recording banned by the Hamtramck mayor and city council. Maki’s deep affection for the music is evident in the extensive research he began decades ago, revealing an overlooked history that helps to establish the beginnings of a thriving local independent recording industry. Our interview was conducted by email.

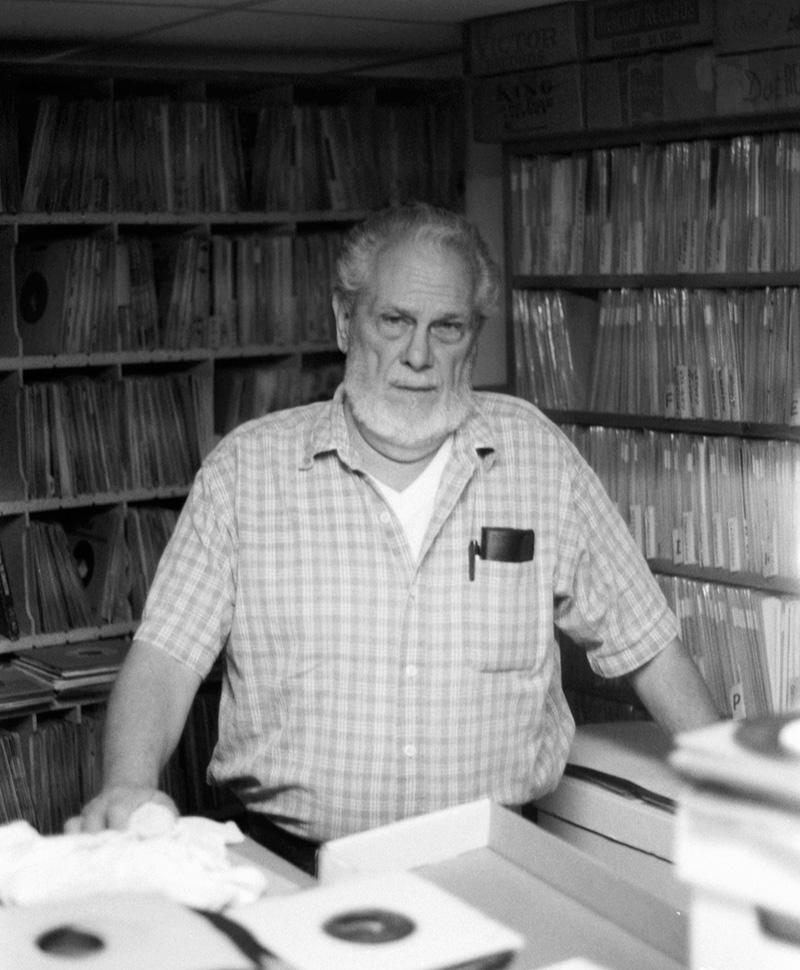

Your book opens with a dedication to record dealer Cappy Wortman who lent you a box of Detroit label 78s, which you wrote, “presented a mystery that soon grew into an obsession” and he was also credited on the back jacket for inspiring your 1999 LP: The York Bros in Detroit. He sounds like an influential figure. Was Cappy helpful in compiling your discography in the back of the book, and is there anything else you remember about him and his shop?

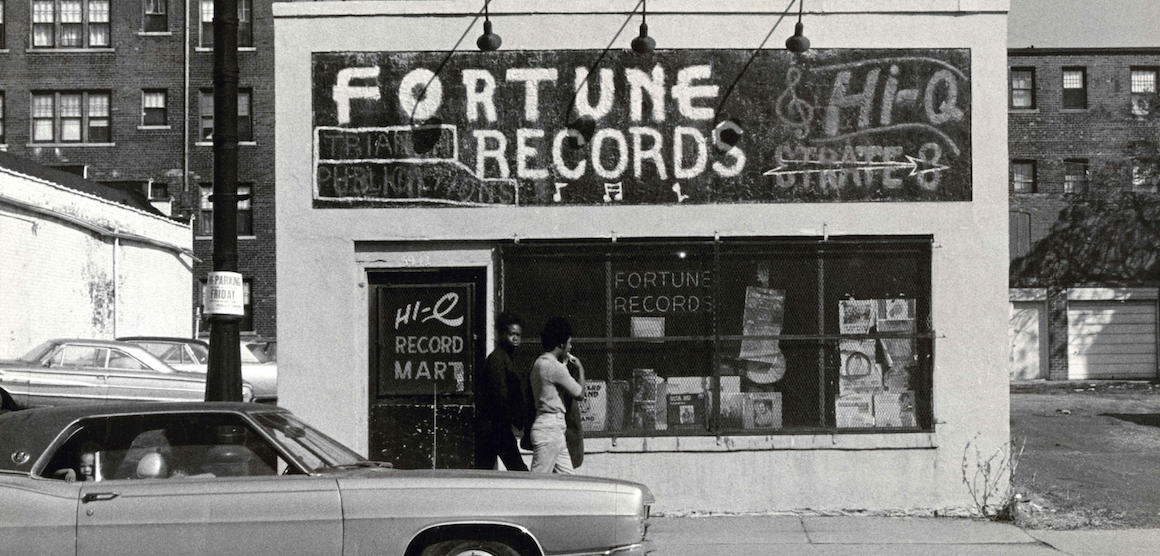

When I was nineteen years old, I took over a weekly one-hour college radio show about rockabilly music. A typical broadcast required me to spin twenty-two tracks on the turntables, so I swept local stores looking for new music to share. I had already started collecting reissues of 1950s rock’n’roll music during high school (the Sin Alley compilations were a real kick). One Saturday afternoon I entered Cappy’s Record Mart, which in 1990 was located on the south side of Eight Mile Road, near Gratiot. When I knocked on the front door, a gruff voice shouted from inside, “Whaddaya want?” He kept me standing outside, traffic whizzing by at 50 miles per hour just a few feet away from me, as I explained what I was looking for, and why. Cappy’s shop stocked only used (that is, original — no reproductions or reissues) records dated 1965 and backwards. Being a novice collector, I picked up a lot of 45s that were in less than perfect condition (ha!). Cappy wore a mustache, grew a short beard all the way around his chin like an old sailor, and combed his hair back like Conway Twitty. He conducted a lot of deals by mail, and nearly every time I visited his shop, I was the only customer. On many Saturday afternoons, we chewed the fat about local music (Fortune Records was a favorite topic — he contributed a testimonial in the recent book by Billy Miller and Mike Hurtt), and played records. Sometimes he’d share cans of beer, and he’d light a cigar. I always left the shop with my clothes smelling like strong tobacco, toting a couple of beat-up records. During the era of compact discs, it was a vinyl lover’s oasis, filled with shelves of 45s and 78s. (Anyone can view the inside of Cappy’s Record Mart by watching the record store scenes of the 1992 movie Zebrahead. The story, set in Detroit, was shot there, too.)

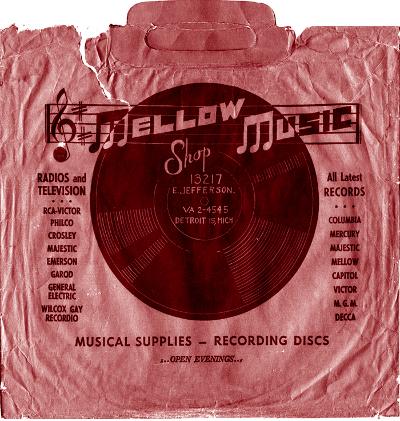

By 1996, I was interviewing local country and rockabilly musicians for my radio shows (I used many of these for the Detroit Country Music book that Keith Cady worked with me on, and University of Michigan Press published in 2013), and some friends helped me assemble a vinyl album of Detroit c&w bandleader Eddie Jackson. Cappy liked the results and suggested that I produce one of York Brothers 78s they made in Detroit. I knew of Hamtramck Mama, because I had a copy of the Fortune LP compilation Skeets McDonald’s Original Tattooed Lady Plus Eleven Other Sizzlers, and had found 78s of the song on Universal, and Fortune. He introduced me to more Universal and Mellow 78s, which no one had reissued in any format. Cappy himself didn’t know much about the labels, except he told me that he bought records at the Mellow Music Shop when he was a boy. Next time I saw Cappy, he loaned me a stack of his 78s so I could copy the music (“Don’t drop that box, or you’ll owe me plenty!”). After we got the LP out, a German friend sent me a York Brothers discography, and a short biography written by several hillbilly music researchers, and record collectors in the U.K. Over the last twenty years, I pieced together the history of the Yorks, Mellow Records, and filled out the discography.

You tell how the “Shoun Brothers” song I’m a Handy Man stuck in your mind while you were renovating your house during the 2020 pandemic—and how that led to you researching it as a Fortune Record bootleg by the Shelton Brothers issued on Decca 10 years earlier. Was there an active trade of master recordings or stampers happening between labels—or how did these bootlegs occur?

Recording studios often made new masters from old records — sometimes to preserve old recordings whose masters had been destroyed, and sometimes to make illegal copies. Because most juke boxes before 1950 played only one side of records, a record bootlegger with access to recording and mastering equipment, and a press could make relatively inexpensive one-sided copies of any hit record. Since the guys at Universal had their own record company with connections to an established jukebox route, they could have made single-sided bootlegged records of just the songs they thought would attract jukebox plays. I don’t know if they did a lot of this, since they were busy making new records.

It was surprising to hear there were 5,000 jukebox vending machines around Detroit in the 1940s. The sheer number of records and coin deposits is astounding. Eddie “The Immune” Kiely is one center of the mystery. He went from car heists to vending machines, and later to producing and creating the Mellow label. Did the record labels have more success than the vending machines, and were artists ever paid royalties from the jukebox sales?

For a while, the record labels sold pretty well. Although the musicians union required royalty payments for recording sessions, jukebox and radio plays to members, I doubt the artists on Kiely’s records were paid royalties from jukebox sales. They were probably paid a flat fee for a recording session. When Kiely opened a music shop to the general public, he still maintained his jukebox route, and eventually left the record making business. Part of the reason could have been changes to the music industry after World War II ended, especially with competition. People created hundreds of independent record companies across the United States.

It was interesting that Hamtramck Mama recorded in 1939, was banned in Hamtramck, and you mention that the ban helped fuel sales. Why do you think such a gritty regional song had such a big national response?

The main reason: the song is very, very funny. It drew listeners in with its outlandish title (what in the world is a Hamtramck?), lyrics that told a satirical tattle on life in a big city (She shook it in the country, she shook it in town / When the preacher saw, he laid his bible down), all delivered with a grin and a wink.

Your theory about United Sound System owner James Siracuse helping out Louie Shoun of Universal Recording Studios with his business rings true. Did you learn if Siracuse was involved with other small labels in the area? Do you think Siracuse also built the lathe for Universal—and was that the same equipment for Mellow and Hot Wax?

Because recording lathes were difficult to purchase, I believe Siracuse could have built the lathe used at Universal Recording Studios, and the records by Universal, Hot Wax, and Mellow labels resulted from that setup. Before and after World War II, Siracuse made custom records pressed in small quantities, depending on what his client could afford. Sometimes the client used a United Sound label, sometimes the client created their own. I’m not aware of Siracuse holding business interests in local labels. However, in 1951 Siracuse, Norman DuFour, bandleader Glenn Moore and others who co-owned the American Record Pressing Company (ARP) — the only record plant in Detroit, at the time — purchased the Vargo pressing plant in Owosso, Michigan. ARP originated around 1946 as Melmore, Inc. The partners moved ARP out of Detroit, relocating to the Owosso plant. DuFour ended up managing American Record Pressing, and the plant made records for labels based across the U.S. until a fire destroyed it in 1972.

You write that when the York Brothers moved to Decca records that “they dished out less enthusiasm than heard on their Detroit recordings.” You also connect the rockabilly three piece the York brothers pioneered as over a decade earlier than the Sam Phillips Sun recordings. That kind of energy in the music seems emblematic of many later Detroit recordings, like those on the Fortune label. What do you think helps explain that?

Before the war, when big bands dominated local stages, small musical units, such as the York Brothers, were the exception. In order to be heard, smaller acts had to perform with volume in venues often crowded with music fans, and I think that necessity was carried into music trends that followed the end of the war, including various types of blues, country, rock’n’roll, and jazz. When these groups entered local studios, they performed with the same energy as they did in night clubs. Recording engineers for major labels usually didn’t allow country musicians to get crazy in the studio, and expected a certain decorum — especially in the early years of the industry. Despite Bob Wills, whose trademark was acting crazy in the studio, most country music recording sessions for major labels were fairly tame. With the success of Hamtramck Mama, Universal Recording in Detroit discovered how well performers who “loosened up” in the studio could sell a record. This idea was temporarily lost, after the war. It came back with Fortune, and other independent companies, as the chaotic, early phase of rock’n’roll played out.

You mention that the Italian mafia in Detroit pushed out Harry Graham from his jukebox accounts, and soon after, Ed Kiely is producing records for Universal and later Mellow and Hot Wax. Was Kiely a reformed con artist, working for the mafia, or was he forced out from the jukebox racket like Graham?

In 1947 Kiely was stabbed and robbed by thugs while making the rounds of his jukeboxes. This could have been mafia intimidation, or just bad timing. He still had a jukebox route in 1950; by then it may have been too small to call unwanted attention to it. I suspect Detroiters knew of Kiely mostly for his Mellow Music Shops. As stated in the book, I didn’t find Kiely’s name in federal investigations regarding mafia infiltration of Detroit’s coin machine operator unions. Harry Graham, the one person you’d think might mention Kiely during testimony, didn’t speak a hint about him.

United Sound Systems was an expert recording studio with a homemade lathe for cutting masters, but they only put out a limited number of records. It seems there must’ve been local factories doing the pressing. Have you found any evidence for local record factories pressing 78s or was record pressing part of the system controlled by the major labels?

Major labels controlled most pressing plants during the era covered in the book. Harry Graham ordered thousands of copies of Hamtramck Mama, so if he used a local plant, it must have run more than a handful of presses. The war made raw materials hard to come by, although most plants resorted to recycling old records. Sav-Way Industries, which introduced Vogue picture discs at the end of 1945, was the earliest record manufacturer I could confirm based in Detroit. It’s possible Sav-Way manufactured records before 1945, because inventors of the picture discs must have been familiar with record manufacturing processes. However, before Vogue picture discs, most Sav-Way activities reported in Detroit newspapers had to do with wartime industry.

Craig Maki’s playlist/soundtrack for Tomorrow Brings Memories can be heard on YouTube

Craig Maki will be signing at Book Beat on April 30, from 1-3 pm on Indie Bookstore Day.

Craig Maki is a writer, musician, and designer. He enjoys photography, drawing, and collecting old records. For ten years, he hosted radio shows on public stations in Southeast Michigan, featuring vintage rockabilly and country music. Maki is co-author with Keith Cady of Detroit Country Music, essential reading for music historians, record collectors, roots music fans, and Detroit music aficionados. His writings are featured online at http://carcitycountry.com/