ELADATL: A History of the East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines

ELADATL: A History of the East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines

By Sesshu Foster and Arturo Ernest Romo

City Lights

“The purpose of art today is to debase, cut the dead weight of the empirical from the dirigible of expansive meaning, then let that collection of gasses expand, coalesce, and bubble up and ignite into intoxicating visions.”

The East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines (ELADATL) existed and may exist still in a recent parallel past and present, a Latinx re-casting of contemporary, historical, and cultural life in the East Los Angeles and Los Angeles areas, reflecting the challenges and creativity of marginalized people of color in Southern California.

Like Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, no matter how often an anecdote is related in ELADATL, the story remains, Roshomon-like, blurry around the edges, and its facts are not always the point. The story—such as it is—concerns ELADATL as (a) the name of a film in fund-raising status, (b) a military group in conflict with the (white-owned) zeppelins of Los Angeles, (c) an under-funded, semi-reliable transportation system for East LA-ers, who have no other way of getting back and forth to work, or (d) all of the above, none of the above, some of the above, perhaps simultaneously.

Bolaño, however, really didn’t have a knack for comedy. ELADATL is often funny for its absurdist scenarios: “The Zoltan Monsanto Institute for Cognitive Dissension originated in 1953, when the death of Josef Stalin allowed select scientific figures in the American Intelligence Community to return to their research endeavors into ESP-Transference and Kinetic Manipulation as related to UFO clubs throughout history, particularly those that multiplied throughout the American Southwest during the 19th and 20th centuries, aided by funding from ‘anonymous’ donors with apparently indefatigable sources of income.” Zoltan Monsanto and his Institute soon give way to the Poet of the Universe, a position Monsanto created before his untimely death. Poet of the Universe and dirigibles—who knew?

Like Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, the premise of what ELADATL seems to be about in the first 50 pages, explodes into a collage of lists, “agent reports,” photographs, notes, and narratives,—all more or less on the topic of the ELADATL from various viewpoints, times, and places. The energy level of the book is high as disparate voices describe eerie, suspenseful scenes, make comedic observations, and recount of historical crimes and atrocities. Recommended: experimental and accessible, briskly paced, with pointed humor throughout.

Mrs. Murakami’s Garden

Mrs. Murakami’s Garden

By Mario Bellatin (Healther Cleary, translator)

Deep Vellum Publishing

“[On their wedding] day, Izu and Mr. Murakami ate alone in a restaurant on the outskirts of the city. It was the only time they would do this after Izu left home. The menu included a dish of flesh sliced from a live fish. The meal was served beside a glass dish containing the fish, and lasted exactly as long as it took the poor creature to die.”

Mario Bellatin is an author new to me but one who apparently has a least six previous books available in English translation. I’ll now make a point of tracking them down. Mrs. Murakami’s Garden exemplifies understated narration that allows the rhetorical effect of implication to knead each reader’s imagination into picturing the emotional ugliness implied. This restrained, understated narration is a trait of much Japanese literature I’ve read. Thus, in terms of simulating the rhetorical tone of (some) Japanese literature, Garden is a stunning success, especially in terms of (a) a Mexican writer imitating (b) a trait of Japanese literature that is (c) successfully conveyed from Japanese via Spanish into English.

In addition to that rhetorical nicety is the subtle twist that turns the protagonist, Izu, from liberal to conservative, yet pariah to all. The transformation is morally horrifying, even though nobody fundamentally changes—only our perceptions of them change because of where the logical conclusions of their worldviews lead them. Playing the long game is Mr Murakami’s standpoint, with sadistic humiliation as its goal.

In weird contrast to the cruelty of the end narrative are the author’s “Addenda” and the translator’s “Note,” which are brief exercises in absurdity. Together they seem to annul the slow-burn seriousness of the story; but I suspect there are dots I’m failing to connect.

Every Color of Light

Every Color of Light

By Hioshi Osada (text) and Ryoji Arai (illustrations) • David Boyd (trans.)

Enchanted Lion Books

Beautifully painted in subdued colors, Ryoji Arai’s illustrations match the mood of Hioshi Osada’s simple, poetic description of a day (in David Boyd’s fine rendering)—from storm to clearing to nightfall—each of the day’s moods embracing broad swaths of color, even during the harshest of the rains. One’s eyes adjust to the color tones, after which details can be made out, suggesting both the range of colors and lushness of life and activity all around. The words are simple enough for most young children to read on their own, but they will probably be most fascinated by staring at the pictures. A good bed-time book too, no doubt.

Summer Solstice: An Essay

Summer Solstice: An Essay

By Nina MacLaughlin

Black Sparrow Press

A poetic essay on summer’s sensual and erotic charms, MacLaughlin’s piece falls within the tradition of exploring and following an idea wherever it goes. In that regard, the challenge for the essayist is to create a sense of “roaming with intent,” and the promise of curiosity that comes with that sense, so as to avoid its opposite: loitering, which quickly bores. As it turns out, MacLaughlin’s roaming with intent does have a structure, too, as its five parts follow the rise and ebb of the season, its changing colors, moods, and association.

Here’s a sample of MacLaughlin’s fine prose, with its ear for rhythm and sonority:

“[Fruit flies] scatter, tickle the private part of my wrist, touch my skin like secrets I’m not sure I want to know. They wait a minute, land themselves on cabinet doors, wing sinkward, and then drift again back toward the sugar juice below the peachfuzz skin. They do not touch down on the onions or garlic bulbs on the hot peppers drying in the basket that hangs from the window trim. The sweet flesh pulls them.”

MacLaughlin’s narrative voice is close and intimate—certainly not one to be loudly declaimed at a slam. Engagement with nature as a personal rather than scientific relationship is also explored in two other recent book-length essays: Daisy Hildyard’s The Second Body and Joanna Pocock’s Surrender. MacLaughlin’s, Hildyard’s, and Pocock’s works each unite truth to aesthetic beauty.

Invisible Ink

Invisible Ink

By Patrick Modiano

Yale University Press

Invisible Ink is weird and well-structured. Like Bolaño, Modiano explores the terrain of approximations, a place where the facts don’t always add up. For Modiano, that place is often our memory—with gaps, guesswork, and evasions. The book has two narrators: Jean Eyben, reflecting on his first case working for a detective agency; the second appears towards the end chapters of the book, suddenly displacing Eyben’s view with that of an omniscient narrator’s.

The story involves a private investigation into the disappearance of a young woman from her apartment in Paris. The investigation goes nowhere but haunts Jean Eyben for the next 30 years. To be clear: There is no evidence or suspicion of foul play. Over time, Eyben begins to suspect he is somehow connected with the circle of people he’s been investigating.

Modiano’s work here is great (as is Mark Polizzotti’s translation, which engages in some very nice rhetorical sleights of hand that I assume make for some hallmarks of Modiano’s prose).

Firmament, No. 1, Winter 2021

Firmament, No. 1, Winter 2021

Sublunary Editions

A new quarterly journal for those who love translated literature—stories, poems, essays, and interviews with translators. Nearly two dozen writers and translators represented here, including Rilke, Inger Christensen, and Eric Chevillard, and many others new to me. (The upcoming Spring issue is promised to be twice as big as the first.) Some of the works here are excerpts from recent and upcoming books in Sublunary Editions’ queue; others are unique to the volume. (For those who subscribe to Sublunary’s books, issues of Firmament are included.)

Snoozie, Sunny and So-So

By Dafna Ben-Zvi (text) and Ofra Amit (illustrations) • Annette Appel (trans.)

Enchanted Lion Books

Snoozie and Sunny may be opposites in some ways but are true, dear friends to each other. Snoozie, the sleep cat, and Sunny, the peppy dog, share an apartment together (presumably belonging to humans—the story isn’t that anthropomorphic).

One day, Snoozie and Sunny hear a strange, unhappy noise coming from an apartment building across the way. Investigating, they find a small, underfed dog named So-So inside of a laundry hamper, who has apparently been abandoned and is living alone without friends or companions. As a result, So-So is shy and unconfident.

The rest of this chapter book shows how Snoozie and Sunny integrate So-So into their lives as a new friend, and how So-So discovers her secret talent.

The Lost Soul

The Lost Soul

By Olga Tokarczuk and Joanna Concejo (Antonia Lloyd-Jones, trans.)

Seven Stories Press

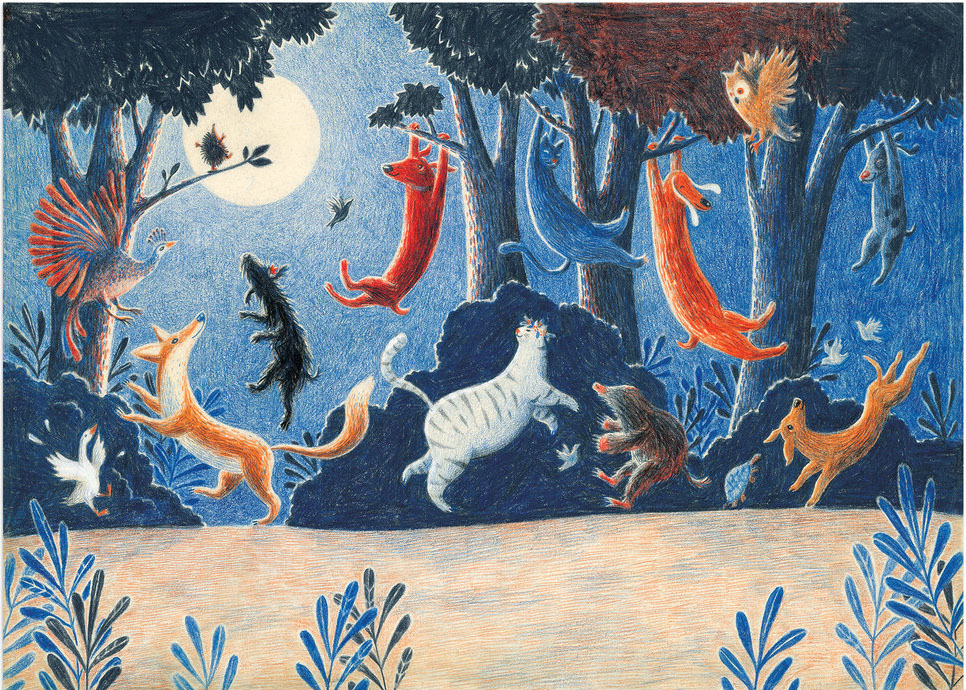

Perhaps the temper of the times will bring these children’s books the (re)newed attention they deserve. They each suggest lives of utter simplicity endured at a relaxed pace—a pace that allows the characters in each book (and their readers) to experience nature in quiet solitude, resulting in lives of enviable contentment. With vaccines against COVID quickly becoming available and the panic beginning to recede, more people may feel in retrospect that there was much to appreciate in the massive, world-wide re-set of our otherwise frenetic pace.

Pace is the explicit theme of Tokarczuk and Concejo’s collaboration. In The Lost Soul, a man who works at such a frenetic day after day, year after year, that he is diagnosed as having outstripped his soul (souls travel much more slowly), and that he needs to exile himself to a type of like at Walden Pond. The quiet is expressed via page after page in Poland-born, Paris-based artist Concejo’s beautiful, whimsical, and sometimes surrealistic drawings. Nobel Prize-winner Tokarczuk’s prose (as translated here by Antonia Lloyd-Jones) is also, as usual, beautiful, whimsical, and sometimes surrealistic. It’s the kind of book marketed to kids, but that will mean far much more to adults, who will probably want their own copy.

Fish for Supper

Fish for Supper

By M. B. Goffstein

NYRB Children’s Collection

Fish for Supper is a masterly gem of prose and illustration. Told as a memory of a grandmother’s day in the life—getting up early, spending the day fishing, eating the fish for dinner, followed by going to bed—the life is orderly but not rigid, and free of fussiness. It is a life in balance. Originally published in 1976, it is also a Caldecott Honor Book.

Only one small picture per page, underscored by a handful of words—fragments of a complete sentence. The first sentence alone is 37 words long told over 5 pictures. I point this out because social media has done much to erode attention spans. The shorter the sentence, the less likely it will be able to convey complex information. Although Goffstein wrote this before the age of attenuated attention, research I’ve read says that even college-educated adults feel intimidated by sentences over 18 words.

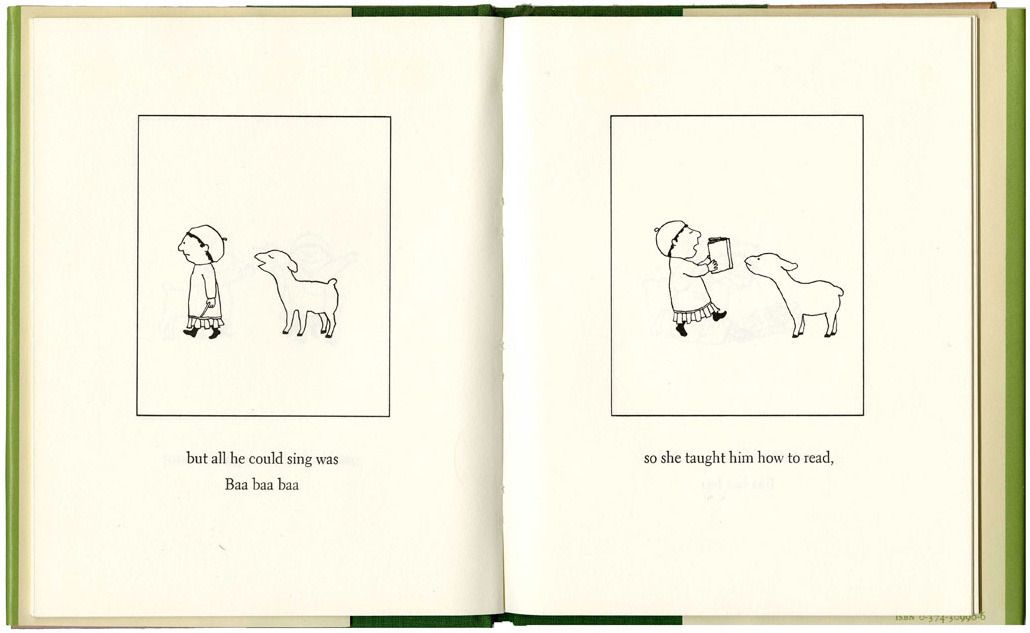

Brookie and Her Lamb

Brookie and Her Lamb

By M. B. Goffstein

NYRB Children’s

Brookie teaches her lamb to sing and read, and though he can only read “baa” and sing “baa,” Brookie loves him very much. They go for a walk to the park, and when they return home, Brookie makes the lamb a comfy bed. The next day, Brookie fills the lamb’s library with books he can read and gives him music he can sing, which makes the both of them very happy. An understated example of joy in acceptance.

The Dreadfuls: A Sensational Treasury of Misadventure & Mayhem, Splendidly Illustrated

The Dreadfuls: A Sensational Treasury of Misadventure & Mayhem, Splendidly Illustrated

Ryan Standfest (Ed.)

Rotland Press

It’s been a few years since the last Rotland Dreadful—a series of grimly humored pamphlets, each featuring the work of a specific artist. Unlike its predecessors, The Dreadfuls is an anthology of miscellaneous writers and artists devoted to the dour side of life. Editor / publisher Ryan Standfest’s eye and ear for selection and arrangement are as impeccable as ever. The titles “How to Fake an Aneurism” (by Ethan Persoff), “Never Good Enough” (Shary Flenniken), and “Precious Rubbish” (Kayla E.) exemplify the tone, which ranges from Dadaist absurdity (Stéphane Rosse) to emotional abuse expressed as love (Kayla E., again). All that and more in a mere 32 pages.