Diary of a Foreigner in Paris

Diary of a Foreigner in Paris

by Curzio Malaparte (Stephen Twilley, translator)

NYRB Classics

Italy is a country of slaves. A country of men continuously exposed, day and night, to the worst violence of the police, the judiciary, and informers. . . What does it matter if the Italian is, individually, a free man? He can think inwardly what he wants: in reality he is a slave, both of the state and of other Italians. If he doesn’t have powerful friends in high places, he is at the mercy of the police, of the spite and jealousy of his neighbors, of the weakness and cowardice of the state judiciary, of the subjection of the last mentioned to the executive and to the parties. I was arrested eleven times in twenty years; there is nowhere in Italy I can sleep easy.

Curzio Malaparte left his native Italy at 16 to fight alongside the French against the Germans during World War I. He joined in 1914 and stayed in France until 1933, when he returned to Italy and, between stints in jail for his writings, served in the Italian Resistance against Mussolini before and during World War II. In 1947, Malaparte returned to Paris, eager to rekindle his lost acquaintances and fond memories. The memories are easily evoked; the friendships not so much, eyed suspiciously as he is because his return to Italy coincided with Italy and Germany forming an alliance, followed by a declaration of war against France.

The diary entries are expansive and detailed, documenting his contemporary Parisian days and nights as well as his memories of before ‘33, memories riven by distinct generational differences he detects between the veterans of each war. These are his memories of “simple people,” more direct and less pretentious than their contemporary bourgeois counterparts. In his diaries, conversations of the night before are recalled, and the words, gestures, dress, décor, and ambience are recorded with such precision as to arouse suspicions of enhanced rather than exact veracity. As a raconteur, the pictures and ideas Malaparte evoke make him an engaged witness.

His habit of seamlessly segueing from conversation, to observation about the conversation, to generalized observations regarding the topic of conversation reminds me of Knausgaard during the many meditative explorations that make up My Struggle. Malaparte’s eye is as prone to harsh judgment as it is to effusive praise, his likes and dislikes asserted with equal vigor.

But all diary entries to not hail from Olympian heights. Malaparte is his own comic relief, as well, indulging readers to revelations of his treasured habit of barking to the neighborhood dogs. At night. For hours on end. In France, this sort of thing is generally tolerated, but not so in Switzerland, where he (briefly) vacations. In the following passage, I can only hear the policeman’s voice as Peter Seller’s Inspector Clouseau:

Yesterday evening, having just arrived in the little inn Pas de l’Ours, which is hidden away in the pine forest overlooking Crans, I called out to the dogs in the vicinity. I went out on the terrace and began to bark. And the dogs immediately responded, from near and far, through the night dimly illuminated by a slim crescent moon. I always do the same thing when I arrive in a new place. I become acquainted with the dogs in the vicinity. I don’t do any harm. But this morning I received a visit from the Crans police, who asked me to stop barking at night.

“You are not a dog, monsieur.”

“I like barking with the dogs, at night. I’m not doing any harm.”

“Such things are not done in Switzerland, monsieur. The regulations prohibit it.”

“Thank you. I won’t do it anymore. But I won’t stay in Switzerland, I’ll return to France. There you can bark at night all you want.”

“I’m sorry, monsieur. Foreigners very much enjoy themselves in Switzerland. It’s just that they don’t bark at night. I believe you are the first.”

“I shall return to France, where foreigners can bark as much as they like.”

“I do not doubt it, monsieur. France is a country of loose morals.”

“To bark at night is not to have loose morals.”

“It begins with barking, monsieur, and finishes with biting. The Swiss don’t like being bitten”

I won’t stay in Switzerland. I’ll leave tomorrow. I don’t like countries where you can’t even bark at night. I like free countries.

Later, he explains that he tried talking in dog language to cats, but “the cats didn’t want me to, and insulted me.”

Malaparte of course records far more than his exchanges with the police regarding his barking, and his insights are vivid, well-described, and related with an enthusiasm for intelligent conversation. It doesn’t take agreeing with his every pronouncement to enjoy the camaraderie and earnestness found here.

The Book of Everything

The Book of Everything

by Mary Ellen Mark

Steidl Verlag

“Something else you can do at night if you can’t sleep, if you’re having a troublesome mind: just look out your window way up at the sky. There’s stars out there by the million, and each one of those stars like people to look at them too and admire them, and they like to be loved. Believe it or not, you can ask them to come down into your room, and they will, they’ll fly right down. And you just put your arms around it and say, ‘Hi pretty star, thanks for being up there, and thanks for being part of the beauty in this world.’ A star will sail right up to the top of the heavens and rejoice and spread the word to the rest of the stars.” — Mona, an inmate in a mental asylum, photographed by MEM

A comprehensive, 50-year career-overview of the photographer Mary Ellen Mark, who died in 2015 at the age of 75 from cancer. Over 600 images are reproduced here—the iconic photographs that built her reputation, as well as previously unpublished shots. One quality unites the photographs across the decades: Mark’s respect for her subjects.

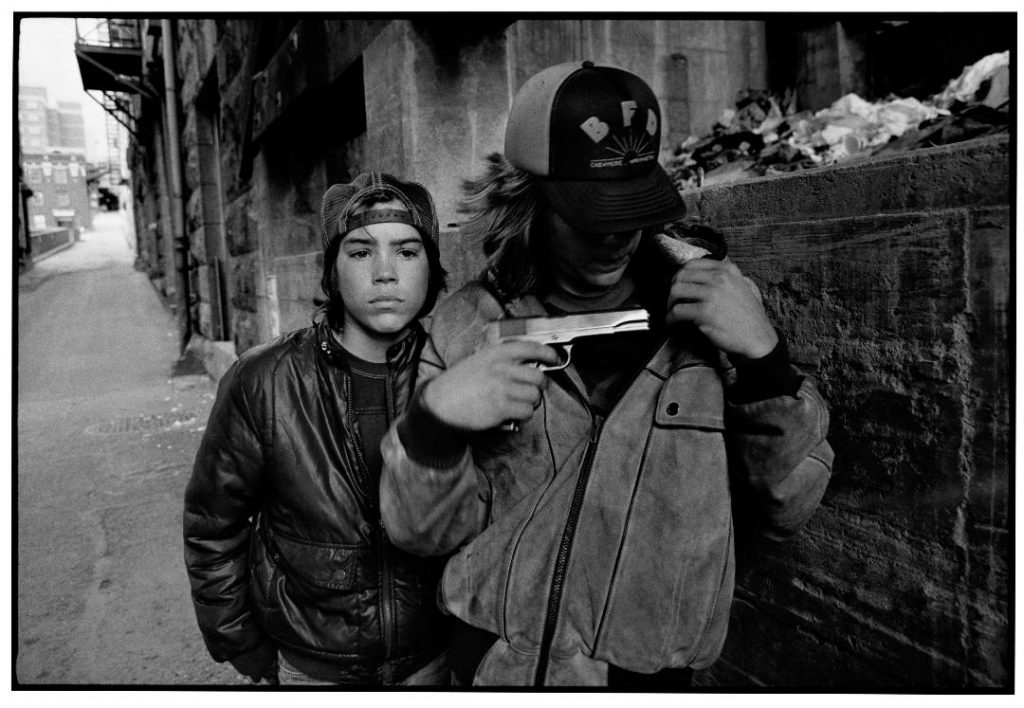

Mary Ellen Mark: “Rat” and Mike with a gun. Seattle, 1983

Because of her empathy, Mark was able to cultivate a level of trust with her subjects that encouraged them to open themselves, to bare some truth about themselves—often in relationship to another person, but sometimes just in relationship to themselves.

Mary Ellen Mark: Amanda and her cousin Amy. Valdese, North Carolina, 1990

Often the lives depicted are harshly circumscribed—men, women, and children around the world in straitened circumstances, searching for joy, companionship, and dignity—or creating it on their own terms. Mother Teresa’s home for “hopeless cases,” for instance.

Or the dysfunctional and homeless families whose photographed lives and attitudes look like a collaboration between Jock Sturges and Nan Goldin.

Or street children—like Tiny (whom Mark photographed for over 30 years)—who started turning tricks and doing drugs by age 13 (when Mark met her) because life on the street seemed safer than at home. Mark photographed Tiny over the course of 30 years.

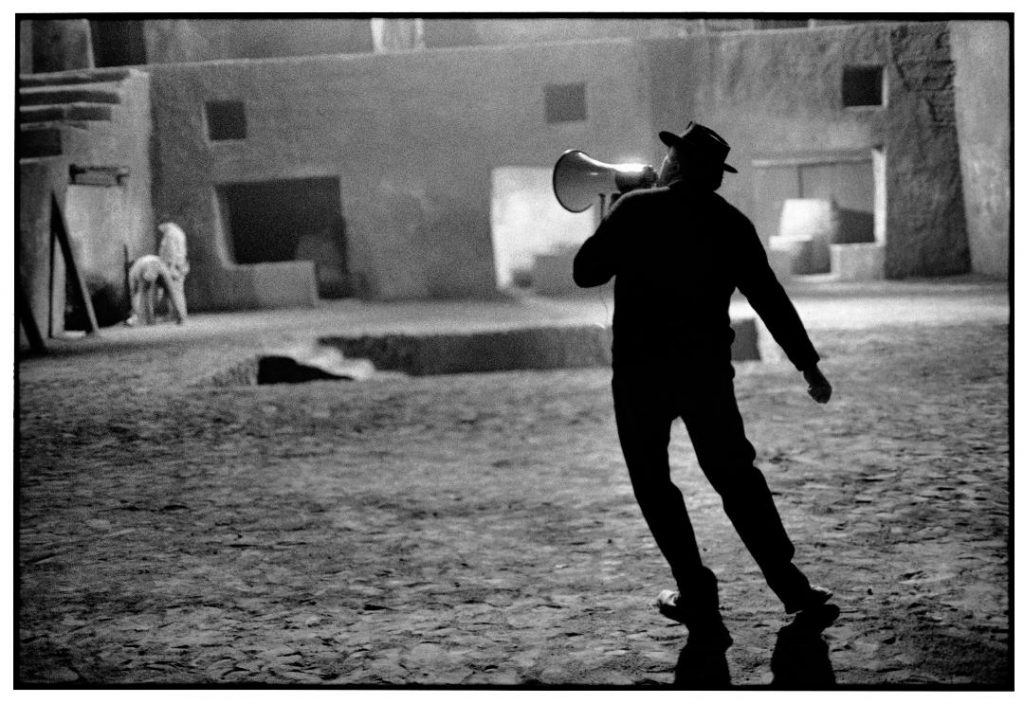

Mark’s camera does occasionally witness grace, however, such as her shot of Fellini directing Satyricon Here, Fellini speaks through a bullhorn on the set. Body and hat are in shadow, arched and suggesting movement: the knees slightly bent, pointed in the same directions, right arm tossed back to thrust the chest forward, the left arm held to the chest, bullhorn in left hand, perpendicular to his mouth. When we focus on the body in shadow, we see Fellini as one half of a pair of dancers on the edge of a bulb-lit city square in the middle of the night.

Perhaps he’s calling down a star.

Mary Ellen Mark: Federico Fellini with a bullhorn during the shooting of Fellini Satyricon. Rome, 1969

The Hole

The Hole

by Hiroko Oyamada

New Directions

Imagine an extroverted version of Kobe Abe’s The Woman in the Dunes or a less menacing version of Kafka’s The Trial: The world we’re entering is simultaneously familiar and unsettling, its rules esoteric. In Hiroko Oyamada’s The Hole, the narrator—a 30ish woman named Asa—and her husband move to a different part of their prefecture after he receives a promotion and a transfer to a different city. Asa’s job is not permanent (although she’s been there for several years) and the pay is poor, so she is willing to move, even though the move will place her and her husband immediately next door to her in-laws, who otherwise rent out the house.

Japanese customs of politeness immediately place Asa in a position of examining neighbors’ statements for nuances of disapproval of her behavior and trying to establish hierarchies of relationships and obligations among them and herself. One day, while walking to a nearby 7/Eleven to run a favor for her mother-in-law, Asa falls into a hole about five feet deep. After extricating herself from the hole with the help of a neighbor, Asa increasingly notices strange features of her rural landscape, including the mysterious creature whose hole she fell into and a brother-in-law she never knew she had.

Oyamada’s novel conjures the spirit forces of Japanese folklore and the mysteries of traditional customs. The weirdness doesn’t require the protagonist to die, as it does in Kafka’s The Trial, just that Asa comply with the unspoken rules or end up like her brother-in-law.

Sound of Snow Falling

Sound of Snow Falling

by Maggie Umber

2d Cloud

A Thoreauvian essay in paintings about a family of Great Horned Owls and their environment. This is not a story but a series of depictions of owls in their natural habitat during their most active times—early morning and early evening. As a result, the pictures are in hues of dusk, shadow, and moonlight. Umber has illustrated the lives of owls before in her book 270? (which refers to the number of degrees in a circle an owl can turn its head). The book comes with a seal of approval from a person who professionally studies owls and who touts this book’s educational value. I loved it for its aesthetic qualities, the hushed, snowy mood it evokes so well.

Ellie’s Voice; or Trööömmmpffff

Ellie’s Voice; or Trööömmmpffff

by Piret Raud (Adam Cullen, translator)

Restless Books / Yonder

Ellie is a little bird without a voice. Everything around her—even the trees—make a sound. But not Ellie. Then one day, while walking along the shore, she discovers a curious object, which turns out to be a horn, and which allows Ellie to make a sound. The sound is more curious than pleasant, but it gets her attention and allows her to feel as if she fits in.

No ray of sunshine is without its cloud, and it turns out that the horn Ellie found belongs to a boy who lives on an island far away, a boy now very sad at his loss. Although Ellie is upset to find that the horn is not hers, she knows she must return it to its true owner. This is a story of joy in self-acceptance and appreciation of others.

Illustration from Ellie’s Voice; or Trööömmmpffff by Piret Raud

Mindviscosity

Mindviscosity

by Matt Furie

Fantagraphics

Matt Furie returns. Four years after the book Boys Club (and a near career-killing appropriation of its character Pepe by various white nationalists), Mindviscosity is a portfolio his stand-alone pictures (plus some panels that seem to be a draft toward an idea that never congealed into a story). His work shows him to be as comfortable with the adult and grotesque as he is with the childlike. (The Night Riders, his book for 4-8 year-olds, came out eight years ago. While Mindviscosity has many images that children would enjoy, this is not a children’s book.)

The cartoon style his best-known works are based on features monstrous and ludicrous faces and figures, rounded shapes, large eyes, and primary and secondary colors. Oh, and a juvenile sense of humor. (No stories here, alas. But he and Johnny Ryan can go head-to-head (as it were) any day, vying for King of Vulgaria—which, in my book, is a feather in their respective tiaras.) And that facet is well-represented. Dozens of different faces and shapes populate the pages—Furie clearly enjoys performing his art without repeating himself. Despite the weird faces and bizarre shapes, there are some pretty mellow monsters here, all looking at home with their fellow freaks.

But there are some surprises here. For one, his nimble draftsmanship of birds. Even more impressive are his pictures of entwined and looped snakes—different species and colors coiling into abstract color patterns. As several pages of enlargements earlier in the book show levels of detail not readily apparent at their usual reproduction size. Clearly, Fantagraphics, Furie’s publisher, want to make the case for the craftsmanship behind the humor.

Mindviscosity is a treat for Furie fans. Newbies should begin with Boys Club or, if you don’t appreciate bong and dick jokes, try The Night Riders, instead.

Movie trailer: [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEiqZWw5vYs]

Röhner

Röhner

by Max Baitinger

2d Cloud

“Mismatched Roommates” is an always-popular topic in storytelling: two opposites, forced (in some vague way) to live together (preferably a small apartment), with coexistence rather than (prison-like) coercion the goal. Here, Röhner is the unwanted guest, and the host is the passive aggressive force that perpetuates the full-on leeching. Bonus points: The quirky woman in the apartment next door arouses the unspoken battle of the testosterone.

Baitinger’s style is simple, geometric, and balanced toward white space—the emptiness seems right for expressing the comedic frustrations with each other shared among the characters.

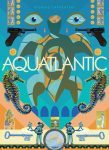

Aquatlantic

Aquatlantic

by Giorgio Carpinteri (Jamie Richards, translator)

Fantagraphics

The conceit here is that most people who live on land believe that stories about an ancient civilization buried undersea are just fables. But in Aquatlantic, the civilization is still alive, and those who live underseas know rather than believe that people used to and continue to live on land. They also know that a meeting of the two peoples would be disastrous for their underwater civilization. Landlubbers are their evil twins: they pollute, and they manufacture and amass material goods far beyond what the natural balance of the biosphere can withstand. The desire for more is both peoples’ original sin. Only those under water atoned to survive.

An undersea dweller named Bho performs in a highly successful one-man show in which he parodies the greedy behavior of those above water. Aquatlantic begins shortly before his last performance, the character of which has slowly been consuming Bho, as Bho increasingly struggles to separate himself from his character, who acts with all the piggishness of ground dwellers.

At the same time, an evil man with a mercenary army are in a ship headed toward Aquatlantic’s location, to kill and capture the Aquatlantians.

Author Carpinteri’s Aquatlantic world is richly imagined. His visual style quotes from various 20th-century schools without becoming self-consciously “retro” or invoking nostalgia for the tales of, say, Jules Verne. If the story is familiar to many of us, for young readers for whom this may all be new, Carpinteri’s illustrations, at least, give the eyes details that spark the imagination.