I arrogantly recommend…by Tom Bowden is a monthly column of small press and books-in-translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired pavement inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

I arrogantly recommend…by Tom Bowden is a monthly column of small press and books-in-translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired pavement inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, ‘This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.’

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If titles are unavailable, please call, we’ll try to help. Most of Bowden’s reviewed books are stocked at Book Beat. Thank you for your support! Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at:

I arrogantly recommend… by Tom Bowden.

Paula Regossy

Paula Regossy

Lynn Crawford

Trinosophes

Paula Regossy—an anagram of Pussy Galore, which inspired the book’s conceit regarding spy craft—consists of a series of “reports” by characters imagined as agents for a secret organization with obscure aims. Being part of the organization means that what the agents say to others (even within the organization) is not necessarily what the agents think or feel—or how they stay sane, since they have no outlet for sincere expression except for the reports they submit to Regossy, their boss, who in turn presents them to us, the readers.

Each chapter’s origins owe to Crawford’s response to a place or work of art in the Detroit area. For instance, the book’s cover shows a painting named “Pussy Galore.” Quotes from the works of other (real) writers seems to suggest notes left behind by previous “spies”—other who also gather information about people, places, and times and turn it into (artistic) assessments of the spies’ place and time.

Undercover detection . . . involves interface. Information is gathered through varying degrees of personal dealings. Our undercover agents infiltrate the life of a person, family, or community to gain enough material to solve or stop criminal activity—such as weapons smuggling, drug production and distribution, or sex trafficking.

Precious little crime stopping is depicted here because Crawford in interested in the mood, temperament, attitude, and filters employed by the agents to do their work—how what they overtly say in a report—what they dare say—may suggest about what they keep to themselves. Thus, Crawford translates the messages found in spaces and works of art into dry bureaucratic reports that readers decode into three-dimensional characters.

INTERVIEW WITH LYNN CRAWFORD

You’ve dedicated your novel to Harry Matthews, presumably because of his novel My Life in C.I.A. How did that novel inform your inspiration for looking at and thinking about people and social systems as existing in a duplicitous world? That surface behaviors—what people say and do—serve only to deflect attention from clandestine behaviors and motivations seems to be a proposition that would quickly lead to paranoia, yet Paula Regossy manages to avoid those perils. How did you manage to do that?

LC: Here’s a story about my long friendship with Harry, who passed away a few years ago:

I had read and loved his novel Cigarettes, and a friend of mine, the writer John Yau, had his address and suggested I send him some of my writing. I sent my very first story, “Solow” (badly typed), to his address (which was long and somewhere in the French Alps). To my surprise he wrote back a glowing response.

Over time he and his wife Marie became close family friends and attended our wedding in Detroit 30 plus years ago. Because of Harry I became fascinated by the Oulipo, a French group of writers and mathematicians employing literary restraints to explore what literature can be. One of the many methods I learned about from them was the sestina, a medieval poetic form based on six words and six stanzas in a specific order. Paula Regossy reads as a novel, but each section began as a sestina before morphing into narrative.

So yes, he influenced Paula Regossy in many ways—and, in fact, every book I’ve written.

I also like the chance to speak of our friendship, because mentorship—with the right mentor—is a beautiful thing.

What ends does the spying serve? I ask because, even though your character Dr. Natambu submits a report in which he claims that the ends of spying are to “stop criminal activity—such as weapons smuggling, drug production and distribution, or sex trafficking,” the other submitted reports have little to say about such criminal activity.

LC: Paula Regossy—along with other agents working in the agency run by Hoss and advised by Dr. Natambu—exceeds at solving crime. I chose not to include those details in the narrative because so many brilliant crime novels already that do that. I was more interested in odd elements of each agent’s personal stories—the internal dialogues, histories, self-doubt, and so on—that led to their careers in espionage. Those choices all depended on the specific artists and artworks that had inspired them [which are listed in the back of the book]. Each section of the novel responds to the specific artist and/or artwork named. In my mind, we were collaborating—possibly the closest I’ll ever get to being in a band—a non-musical band!

Your plain-clothes spies remind me of some of William Burroughs’s agents—say Clem Snide, Private Asshole—whose own work is prone to infiltration from agents of Control. Burroughs seemed interested in exploring personality and systemic types for exploitable weaknesses in human thinking and biology, from which he developed a contemporary mythos. Your spies seem to also take a quasi-anthropological, alienated approach to understanding humanity—and themselves, perhaps—but for different ends, even though both your characters and Burroughs’s struggle with failure. Would you care to comment on, say the similarities and difference between your approach to this book and its characters with those of Mathews, Burroughs, and perhaps other artists whose creations might also include such alienated points of view?

LC: In my mind, each agent shares deep personal doubts and thoughts and ideas and plans and narratives. No one can ever tell a “whole” story. We only hear bits and pieces. A good spy’s job is to be secret. So, what information do they decide to share in a public space? What do they leave out? “After all, there is nothing but failure.” This quote by the great Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard was in my mind through every step of the book. I’ve thought of that quote for years and have come to understand that “failure” is not a reason to avoid something. The act of trying and trying and trying again nurtures something in our humanity.

While Paula and Hoss are present through the book, all the other agents have different techniques, histories, skillsets. Maybe I’m also exploring the notion of “alienated.” A detective must restrict their life in ways that remove them from the loop. But maybe those restrictions offer fertile forms of engagement in other ways.

But what your question really makes me think about is a writing voice. The best writers find their specific voice. I would say to new writers something I say to myself daily—especially when facing doubts, which I do constantly: You be You.

Grey Bees

Andrey Kurkov / Boris Dralyuk

Deep Vellum

Taking place roughly about now, Sergey Sergeyich lives by himself in a village abandoned by all but one other person—his childhood enemy. The village has been abandoned because of Russia’s war against Ukraine, which it has been waging since 2014, and the two sides have been exchanging mortar bombs at distances roughly equidistant from Sergey’s village, Little Starhorodivka, set in an area known as the “grey zone” that no one controls. Sergey, in his early 50s, receives (in a war zone? hah!) a disability pension for silicosis from mining but hasn’t left the village because he wants to keep raising bees, which need quiet rural areas to thrive in.

Despite the bleak setting, meager food supplies, lack of electricity, unnerving uncertainty of the bombings, and proximity to a life-long “enemy,” Grey Bees is often funny, and Sergey is slowly revealed as the compassionate soul he his. There are literal and metaphorical ways of living in a grey zone, and once he literally leaves Little Starhorodivka to find safer grounds for his bees, both begin to vanish.

Before and along the trip he meets two husbandless households with children, one Christian the other Islamic, befriending the wives. He meets Russians hostile to and suspicious of Ukraine and Tatars (the Muslims). He suddenly finds himself—his very existence—under varying levels of threat. The road novel is probably an American invention, but Andrey Kurkov does well at transplanting the genre to Ukraine, a nation that has its own North and South, its own ethnic and religious hostilities, its own faulty distinctions between police and military powers. The point of the road novel is to discover oneself in the face of fellow citizens. In Grey Bees, Sergey proves to be a man of principle and quiet action, whose simplicity should not be mistaken for naivete but for wisdom arising from watching and listening. Although Sergey is described as specifically Christian and consistently observant, his actions, which—once the patina of fear is brushed away—are based on universal principles of grace and decency, consistently engaged: the “do unto others” credo pretty much every faith has some version of.

Boris Dralyuk’s translation of Grey Bees is excellent, and I strongly recommend it as way into seeing the current conflict from the point of view of those just want to get through life and act as decent people.

Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise

Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise

Gary Panter

NYR Comics

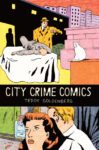

In the early 1980s, I went once a week to the Eye of Agamotto, a second-story walk-up comic bookstore in Ann Arbor run by a guy named Norm. His shop was small but eclectically stocked. I was on the lookout for new artists in the Underground Comix tradition, and Norm had them—specifically, the new Raw series edited by Art Spiegelman (a name I respected) and Françoise Mouly (who was then unknown to me). They were oversized, printed on heavy paper, and ugly. Norm moaned that the new Raw One-Shot—Jimbo by Gary Panter—was “practically begging people, ‘Please don’t buy me!’”

The aesthetic of that original printing of Jimbo was brutal in a way I immediately loved: corrugated cardboard covers, black electrical tape for the binding, quickly yellowing newsprint stock, and images seemingly carved onto the page, momentarily incoherent patterns that eventually resolved into animated life. What the new NYR Comics version lacks in cardboard, tape, and newsprint it makes up for in production values and additional images. And Panter’s images remain as disorienting as ever by rendering objects from a variety of viewpoints and in a variety of styles, often at the same time.

The technique matches the content in Jimbo, which takes place in a post-apocalyptic world—devastation, predation, self-reliance, and vulnerability permeate the afterlife of a planet driven to chaos by consumerism and nuclear weapons. It’s often funny, too, watching Jimbo—spikey haired, skinny tied, thong-wearing punk—bumble his way through bizarre situations, including an escape from a band of human-sized cockroaches whose leader has the head of Donald Duck, on which he wears a beret. The visual climax of the story is created by overlaying two images—one in blue grey, the other fluorescent orange—a double-exposure that destabilizes and energizes the picture, in perfect conjunction with the overall theme: The death of Jimbo’s horse, which is every bit as significant to the book’s theme as the horse in Picasso’s “Guernica.”

The concerns of 40 years ago remain the concerns of today, and Panter’s art remains as vibrant and aggressively alive as ever.

I care for all my characters. I don’t like bad things to happen to them. But they get into sticky situations.

–Gary Panter

Read an interview with Gary Panter from Artforum.

City Crime Comics

City Crime Comics

Teddy Goldenberg

Floating World Comics

“Mary Worth” meets Glen Baxter: Surreal soaps / domestic dramas done up in ‘50s-era deadpan style, with muted tones in a simple palette, and simple, minimal lines to suggest setting. 80 pages of non-stop absurdities.

Reverence: Death Valley

Reverence: Death Valley

Jennifer Renwick and David Kingham

LensWork Monograph Series 19

Photographs of Death Valley in color and black and white across 60 full-page images. Traces of fluid paths—wind and water—are scarred everywhere into the rock and soil, gracefully along sand dune spines and brokenly in clumps of arid-hardened soil, shadows pulled through the day. Many photos are cropped so tightly, the context can’t be made out, making the natural figurations in the land look like abstract paintings. Death Valley is shown as a place of surprising, remarkable beauty, rich in natural variety and color (other than green).

Book of the Cold

Book of the Cold

Antonio Gamoneda / Katherine M. Hedeen & Victor Rodríguez Núñez

World Poetry Books

A book-length prose poem musing on life, death, illness, and suicide told over seven sections, in a format that almost dictates how it should be read: a few lines per page to set in place images and feelings, with the remaining negative space on each page a place for reflective, performative meditation of the scene. A page with, say, three sentences / stanzas doesn’t necessarily translate as a page quickly read, where “read” is taken to mean the reflection and empathy required to understand. Here are some lines from Section 5: Saturday:

Your name was only wind on the lips of the suicides.

Your face was worked by the rain: on the blind mask appeared miserable grooves and eyelids and a yellow mouth, but it kept raining and, for a moment beneath the transparent strands, your face was possible and its beauty blurred with the light, but it kept raining and it got lost like the earth worn down by the weeping.

Your name and face are indecipherable; maybe you didn’t exist,

still you’ve reached old age and make impure motions,

indecipherable too.

The Subplot: What China Is Reading and Why It Matters

The Subplot: What China Is Reading and Why It Matters

Megan Walsh

Columbia Global Reports

What sorts of stories captivate the imaginations of one-point-three-billion people? Or asked perhaps more honestly, What sort of stories does an authoritarian government allow its people to be captivated by? Megan Walsh, a specialist in Chinese Studies who has also lived in mainland China, covers a topic that, for book and culture lovers, is interesting for a variety of reasons, and my own experiences in Shanghai confirm some of the facts Walsh reports here.

Back in 2007 or so, I talked to a young tour guide in Shanghai who was also a hack romance writer. Through her, I discovered that Chinese publishing has an entire division devoted to online serialization of novels, which the authors generally update daily. My tour guide told me she submitted about 3,000 words a day for the novel she was currently writing. Although my jaw dropped at that figure, Megan Walsh reports that 3,000 words a day, while typical, is on the low end of the scale—some writers crank out 20,000-30,000 words a day (that’s about 120 pages in a book) for novels of which Chapter 300 might mark the quarter-way point. I have no idea how somebody simply types that many words a day, let alone improvises a storyline for 12 hours. But as Walsh notes, “Lack of character development and moral maturity is almost certainly a by-product of the speed with which these novels are produced. . . a process that is by necessity knee-jerk and nonstop, requiring characters that are all action and no reflection.”

Publishers allow readers, for various set prices, to subscribe to specific authors or to general categories of novel. Authors are paid (or not) according to the number of clicks and likes their writing generates; ditto for whether authors have a book contract or not: A sweatshop for nerds.

The Chinese government can and does step in any time it likes, based on the whim of the day, to determine which books—electronic or in print—suddenly cause offence. Legal terminology in Chinese law is often left vague and/or incoherent, but most writers know which topics, names, and dates to avoid. Although I can find books in China that I think of as “mysteries,” Walsh reports that “the term ‘crime fiction’ is not widely used” because—in the Best of All Possible Worlds, which Chinese Communism surely must be—crime does not occur, and so we have instead “public security literature.”

What is easier to get past censors is science fiction. Set in other times and places, and perhaps inhabited by different people, current issues and points of view can be acted out through analogy. Writers have for centuries had to devise ways to skirt around censors who were hounding after everything from sex to religion to politics, often with excellent imaginative results by the artists. Some Chinese science fiction writers are also emerging with great success into the English-speaking world and the international stage—Liu Cixin’s Hugo Award-winning Three-Body Problem probably the best known to date—indicating that the topics China’s writers address are universal concerns:

Many writers are genuinely concerned about humanity’s relentlessly self-centered instincts. In Hao Jinfang’s ‘The Loneliest Ward,’ people lie in bed being drip-fed positive feedback until they die, while in Xin Xinyu’s ‘Farewell, Adam,’ they surrender their youth to become part of an amalgamated personality for a teen idol. In the ironically titled ‘The Path to Freedom,’ by Tang Fei, a family that quarantines in the hope of surviving apocalypse outside discovers, too late, that by avoiding biohazardous air, they have failed to evolve the gills and yellow pus required to survive it.

Young writers of mainstream literature and poetry, too, are conscious of and worried about ecological devastation and the costs coming due for rapacious growth. Walsh quotes the writer Xu Zhiyuan, who says the “meaning behind old trees, flowing water, jueju poems, moonlight, and temples has all vanished, to be replaced by tall buildings, neon lights, automobiles, glass, metal cement, profits and earnings, and high interest rates. I do not know how to extract poetic meaning from those things.”

Megan Walsh’s The Subplot introduces English readers to some of China’s writers trying to extract meaning from contemporary experiences, and where to find them.

A Woman’s Story

A Woman’s Story

Annie Ernaux / Tanya Leslie

Seven Stories Press

After Annie Ernaux’s mother died, Ernaux wrote a brief book about her and their relationship, much as she had for her father in A Man’s Place. Ernaux’s style blends biographical re-telling with comments about what she’s going to do in the book, what she was thinking at the time the actions described occurred and what she thinks now in retrospect. Ernaux’s reflections never stall the narrative but instead draw it along a smooth, inevitable seeming (but never predicate) track.

Readers familiar with A Man’s Place will recognize many of the same incidents up through Ernaux’s adolescence. Proximity to her mother changes Ernaux’s attitudes toward her. When Ernaux leaves for college, “Then I understood what it meant to be free. I forgot about our arguments. When I was studying at the arts faculty, I saw her in a simpler light, without the shouting and the violence. I was both certain of her love for me and aware of one blatant injustice: she spent all day selling milk and potatoes so that I could sit in a lecture hall and learn about Plato.” The physical distance between them quickly becomes a cultural and economic gulf as well—an alienation brought about by her mother’s sacrifices. Getting what you want (for your children, say) doesn’t necessarily mean getting what you want (for your relationship with them.)

Although separated in learning and taste, when Ernaux prepares to wed, “We entered a new period of intimacy, revolving around the pots and pans to buy and the preparations for the ‘big day’ and, later, around the children. From then on, these were the only things that brought us together.” Welcome to middle age with children—which eventually becomes middle age without children but with mom again, due to her increasing fragility. “From now on, I shall have to live my whole life in front of her”; “the people of the town where she had spent fifty years of her life, the only people who really mattered to her, would never witness the success of her daughter’s family.”

What their living together again means in practice is that “We had gone back to addressing each other in that particular tone of speech—a cross between exasperation and perpetual resentment—which led people to believe, wrongly, that we were always arguing. I would recognize that tone of conversation between a mother and her daughter anywhere in the world.”

Ultimately, Alzheimer’s takes root in her mother, a miserable existence for the two over the next year and a half. As her mother’s ability to make meaning wanes, so does Ernaux’s ability to describe—not a decline in style or technique but in continuing to record and assess her mother’s person and their relationship. The physical and emotional horrors caused by Alzheimer’s seem unique to each family but the level of heartbreak seems the same for all who have had to endure them. In either case, Ernaux’s essay evanesces along with her mother’s soul, but leaving behind a better understanding of who she and her mother were and how they got there.

Although the “a” of the book’s title implies “i.e., me mum” in the same way it implies her father in A Man’s Place, Ernaux’s memoir of her father, the “a” could just as well apply to Ernaux herself. Not that her story is the same as her mother’s but that her story would not be as it is without her mother’s: Ernaux’s story is inevitably stuck in the ever-present history that is the crowded self.

Three Prose Works

Three Prose Works

Else Lasker-Schüler / James J. Conway

Rixdorf Editions

Else Lasker-Schüler was a German writer, artist, and performer in Berlin in the early decades of the 1900s, numbering among the cabaret avant garde at the outset of the 20th century and, later, titling and contributing to a journal that ushered in Expressionism to German art. Despite winning in 1932 the Weimar Republic’s highest literary award, she almost always led a hand-to-mouth existence, with a child in tow. Cabaret often merged the visual, aural, or oral arts to create a type of pop avant-garde, as when she and her friend Peter Hille performed as a duo named “Teloplasma.” Her sex-positive writing and performance were unusually liberal for the day, and what attention they brought her—including winning in 1932 the Weimar Republic’s highest literary award— did nothing for her economic standing, which was hand-to-mouth-plus-tubercular-child. Yet, her independence was vital to her.

The three works in this volume “The Peter Hille Book,” “The Nights of Tino of Baghdad,” and “The Prince of Thebes” all share in common a character named “Tino”—Peter Hille’s pet name for Lasker-Schüler and one of the names she adopted for herself in letters to close friends, along with “Prince of Thebes.” Knowing those two facts pave the wave to understanding the fables in these three works as metaphors for her life as an independent woman: taking on and disposing with gender identities as they serve her purpose—moves necessary for women to take to become truly independent. While the character of Tino may be described in today’s terms as “gender fluid,” Lasker-Schüler uses the trope of “adult male” to represent the gender-specific experiences and privileges available gentile men, which, in the guise of Tino, Lasker-Schüler is able to also explore, experience, and report.

More than mere exercises in German Orientalism, circa 1906-1920, the fable-like vignettes making up the three works have behind them experiences more real than pretenses at pagan rituals, love, friendship, and godliness, occurring in an India, Egypt, Constantinople, and Jerusalem as indistinguishable from each other as their people—Muslims, Jews, and Roman-era pagans, whose obscure, arcane practices are distinctions without difference, ultimately serving the same metaphysical purposes as each other. This was the Jewish Lasker-Schüler exploring Semitism (the Orient) at a time of virulently rising anti-Semitism.

James J. Conway—the book’s translator, editor, and publisher—believes the three works here stand on their own well enough as to not require an introduction. My own experience with the book, however, suggests that—given the amount of time that has passed since their original publication, and given their level of obscurity among works translated into in English (even though other of her works are currently available in print)—my reading would have benefited from first reading the Afterword. Context supplies what mere text—even a close reading of it—cannot do itself. But your mileage may vary.

Pages from the Diary of a Jackass

Pages from the Diary of a Jackass

Ante Dukic / Vincent Georges

Sublunary Editions / Empyrean Series

Donkeys have, for millennia, served literary duty as indexes of innocence—beings free of cultural opinion, biases, and assumptions—usually in the context of the author’s contemporary society—presented as invariably and cynically corrupt in comparison. Symbols of power—Earthly representatives of Church and State—are shown for the all-too human hypocrites they are, blithely doling out their petty whims against plebes and donkeys alike.

So it is with Pages from the Diary of a Jackass, the first account by a literate donkey I ever recall reading, this one written in 1925 by Ante Dukic (1867-1952), a Croatian writer whose works have been translated into half a dozen languages, including English. The first English translation, which this reprints, is from 1931, at the height of the Depression, when a quarter of the U.S. was confronting employment, home, and food insecurities—a population ready for the book’s message from the lowest of the low. The Jackass represents the obedient worker habitually wronged by his “master,” who beats him for any reason or no reason at all.

“Seeing me drink [at a river], the master murmured: ‘My, how drunk I was last night! Worse than ever—rather better than ever; but I was never more sober than this morning. Only that white wine is something terrible. I still feel its flame and a few glasses of fresh water would be a blessing.” Saying that he banged the stick over my shoulder.

“Aha,” I thought, “this is the thankfulness for bringing him home safely.”

After years of this sort of treatment, the Jackass loses patience with a number of children taunting him, and kicks them off, sending them running away. “And so, I found the truth which I wasn’t seeking: he who wants to have peace, must show his power.”

And yet, that discovery doesn’t make the Jackass eager to exercise the power he does have. The example of oxen shows him that animals more powerful than himself kowtow to their masters, nonetheless.

This afternoon I got another merciless beating from my master. Why didn’t I kick him properly?

Of what use is all my power if I have not sense enough to use it?

Look at the ox. . .

He is strong. He has horns and force behind them. He could use both to defend and to free himself.

But instead, it bears his burdens quietly.

Why?

Because they harnessed him. They killed his spirit of joy, life, freedom, and forced a harness upon him. The harness made him meek and now he has no courage to throw it off.

There’s no revolution of enlightened, self-emancipated donkeys to come to the rescue the Jackass. But surely people know better how to break their bonds.