The following is a partial list of books enjoyed by Tom Bowden, a local educator, obsessive reader of quality lit, cultural flâneur, and longtime friend of the Book Beat. We’ve invited Mr. Bowden to comment on some of his favorite titles published during the past year.

Literature:

All My Cats by Bohumil Hrabal.

All My Cats by Bohumil Hrabal.

A short moral story about . . . well, “pet ownership” hardly does it justice. This is not a happy-clappy book about an old man and the neighborhood cats (a là William Burroughs, say), but a story of love, cruelty, guilt, and redemption without absolution.

Somehow I had reached an age when being in love with a beautiful woman was beyond my reach because I was now bald and my face was full of wrinkles, yet the cats loved me the way girls used to love me when I was young.

–Bohumil Hrabal, All My Cats

August by Christa Wolf.

A short, beautifully rendered tale of remembrance by a recent widower, August, of his seasons in a tuberculosis hospital as a child shortly after WWII and the teenage girl, Lilo, who protected and befriended him

Head-to-Toe Portrait of Suzanne by Roland Topor.

The left foot of a morbidly obese man turns into the shape of his old girlfriend, Suzanne. Old love is re-kindled and explored; jealousy and unfaithfulness ensue; vengeance and retribution provide the tragic ending. Yes: one man’s desire trips him up.

Mac’s Problem by Enrique Vila-Matas.

Mac’s Problem by Enrique Vila-Matas.

Perhaps my new favorite among Vila-Matas’s works available in English—the usual extensive literary references, allusions, quotations, and paraphrases, coupled with an inane but simple plot allowing for / requiring frequent diversions, anecdotes, and essays in which Vila-Matas’s narrator weaves fiction and “reality” together in multiple, fugue-like ways: theme and variations, playing to the narrator’s stated love of repetition, never the same way twice. “Mac’s Problem” is a celebration of the human imagination, and an encouragement to readers themselves to create.

‘I like to show some restraint when it comes to making things up…’ The Spanish novelist Enrique Vila-Matas discusses the role of risk in writing, the ‘crisis of the novel’, and five books that have shaped his own work. –Five Books.com

Rock, Paper, Scissors, and Other Stories by Maxim Osipov.

Rock, Paper, Scissors, and Other Stories by Maxim Osipov.

Because Osipov is a small-town practicing physician who uses physician narrators or characters with close connections to a physician, comparisons to Checkhov are probably inevitable (and accurate). Take Checkhov’s characters, transplant them to present-day Russia (Osipov was born in 1963), little has changed but the technology and hovering presence of a corrupt, citizen-hostile government. Osipov can be funny, too, and Alex Fleming’s translation of “On the Banks of the Spree” captures the flow of conversation idiomatic to U.S. ears. So, hats off to Fleming for his fine translation work; “After Eternity” purports to be a former theater worker’s notebooks, left behind in the offices of the doctor who presents them to us. The narrator is, I suspect, the type of physician Osipov can’t stand. Here’s the narrator on how much he loathes patients who hope they can get his signature for disability benefits: “[Those patients] I refuse ruthlessly: show any sign of yielding and you’ll get a stack of requests under the door. Medicine is serious work; we aren’t in the hospitality trade, thank you very much. . . ” And later, on a different matter: “[I]f one begins hospitalizing patients not for medical reasons but on humanitarian grounds, on the grounds of personal sympathy, what would that lead to?

Ash before Oak by Jeremy Cooper.

Although Thoreau is never quoted in Cooper’s novel about recovering (if that’s the word) from suicidal depression, one line from “Walden” summarizes much of the emotional and intellectual territory covered in “Ash before Oak”: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Our narrator chooses life over death, but not before a profound internal struggle with himself and his relationship to friends, family, and lovers.

Birthday by César Aira.

One of Aira’s better improvisations, this one a musing on turning 50. (Is this Aira talking or “Aira” talking? Doesn’t really matter.) A novella in the form of an essay—Aira is a great BSer, and along with nonsense are liberal sprinklings of insight; at its best the distinction between the two isn’t always clear. The essay is on life, what we think we know (or should know by now, already!), and memory. And another worthy translation by Chris Andrews.

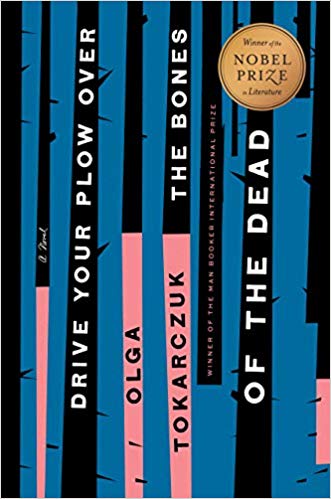

Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk.

Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk.

I love Tokarczuk’s ability to create eccentric characters of substance, characters you can sympathize with if not wholly agree with. In this case, it’s Janina Duszejko and her circle of friends who live in a small Polish village where a series of hunters have been killed. Antonia Lloyd-Jones’s translation presents a strong, convincing voice for Mrs Dusejko that sounds individual and cranky.

Agnomia by Róbert Gál.

A cryptic summary: At some point late in this novella, the narrator lists Thomas Bernhard, Georges Bataille, and John Zorn as his intellectual heroes—three artists whose works explore the extremes of human thought, behavior, and ethics. Gál has his own obsessions, metaphysical and physical, which are explored here in a medium that combines and (con)fuses fiction and nonfiction.

Memoir:

The Big Love by Florence Aadland.

If anyone deserves credit for this book, it’s Tedd Thomey, the ghostwriter behind the voice of Mrs Florence Aadland, the memoir’s putative author. Think late-career Shelly Winters with that brassy Brooklynese accent barking away in perfect obliviousness to the horrors she routine spews. That the book has a coherent narrative flow must also be due to him, since anyone so self-obsessed and reality-shy can hardly be expected to plot out anything. If it helps, imagine the book being told by Trump’s mother. Most people now probably neither know nor care who Errol Flynn was, so the only point in now reading “The Big Love” is as a document—a testimony sans mea culpa—of wanton child abuse. That is, “The Big Love” records the affair between Aadland’s 15-year-old daughter and the married, 50-year-old Flynn. The book is “enjoyable” to the extent that manipulation, self-deceit, and rape are ever funny. For social workers and psychologists, the book is probably an animated version of the DSM-V.

Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II by Svetlana Alexievich.

Interviews with dozens of Russians who were children (2-14 years old) when WWII broke out. Many horrors and depravations are reported, unforgivable atrocities committed and witnessed, and almost everyone speaking here is emotionally traumatized still. (The book was originally published in Russia in 1985.) Despite that, almost everyone interviewed here owed their ability to survive the war because of someone else’s act of kindness or bravery. Children survived as orphans because a stranger said, “I will be your mama.” Moving and highly recommended.

And How Are You, Dr. Sacks? A Biographical Memoir of Oliver Sacks by Lawrence Weschler.

And How Are You, Dr. Sacks? A Biographical Memoir of Oliver Sacks by Lawrence Weschler.

Two of my favorite non-fiction writers and their 35-year friendship. The first 325 pages of this book are based on notes Weschler originally began for a profile of Sacks for the New Yorker. After 10 years or so of note-taking (!), Sacks asked Weschler to kill the profile, since he didn’t want his homosexuality to even be inferred by the piece. In the months before Sacks died, however, he gave Weschler the green-light to publish this memoir, having already outed himself in one of his autobiographical books. . . Anyhow, the writing is first-rate, the facts about Sacks and his life astounding, and the sheer enthusiasms of the man burn through.

Surrender by Joanna Pocock.

An Irish-Canadian (via London, England) has a mid-life crisis in the American upper-mid-West (Missoula, Montana and environs) that coincides with our world-wide ecological collapse. Thoughtful, engaging, articulate, and intelligent, Pocock’s book for the first half combines memoir with American history, natural and political. In the second half of the book, when Pocock returns to the American West without her husband and daughter, Pocock’s book becomes increasingly intimate as her sense of self-discovery leaves her increasingly uncentered during her ecological explorations, and her Romantic notions of connectedness to the Earth clash with her rational knowledge of the possible/probable about what can and will be done to restore the balance between humans and nature.

Happening by Annie Ernaux.

French novelist Ernaux’s account of her near-fatal (illegal) abortion in Paris, 1963, which she didn’t write about until nearly 40 years later. Her account is frank and sober-minded, and it won’t change minds over the debate about abortion. A couple of scenes are brief but harrowing, especially so for women, I imagine, who can better appreciate the sensations specific to their own reproductive systems.

Current Events:

New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi and K-Pop by Fatima Bhutto.

In addition to exploring and explaining the origins and evolution of three modes of “soft power” from Asia (i.e., cultural rather than political influence), Bhutto also shows the ways in which economic, cultural, and political forces shape these modes and the values they express. Not much on K-pop, however, compared to the chapters on Bollywood films and Turkish dizi soap operas, but what Bhutto gleans from her research accords with her longer profiles of Bollywood and dizi: Long on placing family interest above self-interest; esteeming hard work and honesty; and being something the entire family can enjoy together. Not surprisingly, there’s a fair amount of tension between these traditional values as acted out and the lives lead by those doing the acting (and singing).

Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet by David Kaye.

A clear, concise guide to what is at stake in policing content online, especially that which appears in various social media platforms. In addition to differing attitudes around the world regarding the idea of “protected speech,” Kaye makes it clear, in this even-handed report, that Mark Zuckerberg has been a significant hold-out on making significant changes to content moderation, since content moderation has the potential to obtrude into profit making. (I suspect that Zuckerberg isn’t yet willing to end his adoration of St Ayn Rand and the significant amorality of libertarianism.) Ironically, Zuckerberg (with his libertarian delusions) and authoritarian rulers end up deliberately being the world’s largest purveyors of false information.

Field of Battle by Sergio González Rodríguez.

On the causes and consequences of Mexico’s drug wars by the reporter Roberto Bolaño hired to provide him with information regarding the thousands of murders of women in Ciudad Juarez for Bolaño’s novel 2666. González Rodríguez combines first-hand eyewitness accounts with discussions of the theoretical underpinnings behind the social, economic, military, governmental and extra-governmental structures and mechanisms supporting and reinforcing the current nightmare in Mexico, in which the government, military, drug cartels, and drug gangs battle within and among themselves and each other, leaving no room for civilians, who are killed with impunity by the government and criminals for being in the way. The theory becomes tiresome at time, esp. in contrast to pages 84-98, in which González Rodríguez describes various people murdered, including how and why. These passages are as horrifying as any found in Bolaño’s 2666, and are likelier to promote outraged responses among readers than theoretical analysis, however important but about which readers may disagree, a distraction from the immediate, on-going problem.

Politics:

Betraying Big Brother: The Feminist Awakening in China by Leta Hong Fincher.

Excellent reportage on the Chinese government’s hostility toward women in general and feminists in particular who demand rights equal to men’s. No surprise that a so-called communist government uses deliberately misinterpreted doctrine to hold back over 50% of the nation’s people in order to perpetuate male-centric power.

Biography:

Nobody’s Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead by Bill Griffith.

Nobody’s Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead by Bill Griffith.

A beautifully illustrated, well-told and -researched biography of sideshow performer Schlitzie the Pinhead. Griffith illustrates Schlitzie’s life with compassion and dignity, and shows him as somebody who—though sold at age 8 by his family to a circus promoter—was loved and protected throughout his life, primarily by circus freaks and managers. The material record on Schlitzie seems scarce, and Griffith doesn’t hesitate to show the profound emotional duress Schlitizie often endured, be it separation from his mother at age 8 or jeers and physical abuse from circus-goers, Schlitzie was fortunate to have a community of freaks to look after and love him. Two emotional peaks in the book worth noting: Griffith’s depiction of a pair of beatniks discovering and digging Schlitzie’s free-association patter, which had me nearly in tears; and his depiction of Schlitizie abandoned to the LA County Hospital in his later (but not last!) years, which will turn on the taps from a different direction.

After months of source reading and several key interviews I did with two people who knew Schlitzie in his later years, I felt I was well grounded enough to make educated guesses about how events would play out. Cartoonist’s intuition! —Bill Griffith interview in Comics Journal.

General Non-fiction:

Axiomatic by Maria Tumarkin.

An Australian by way of Russia, “Axiomatic” is Tumarkin’s debut in the U.S., a collection of essays that, for their flinty stare-down of ugly social truths, remind me of Didion and Vollmann at their best: no happy-clappy endings, but perhaps some bracing realities met and understood. Topics include the effects of teen suicide on siblings, school mates and teachers, and small communities; a Holocaust survivor jailed for hiding her grandson from a physically abusive step-father; the trauma of refugee life, etc. Probably the single-most powerful book I read this year.

Animal Psychology:

Dog Is Love: Why and How Your Dog Loves You by Clive D.L. Wynne.

I don’t usually buy books about why dogs are so darn cute, but I am increasingly interested in human-dog relationships, which seem to be emotionally symbiotic. Wynne, an animal behavioralist who specializes in dog behavior and dog-human relationships, writes as a scientist recovering from the notion that dogs have no emotions. The prose is clear and accessible and written in anecdotal form, so anybody interested in what science has to say, without knowing science, will find the book accessible and convincing. The upshot is that humans and dogs share behavioral, biochemical, and biomechanical markers that draw them together. Some studies, in fact, show that when a closely bonded dog and human sit together, their breathing patterns and heartbeat rates soon synchronize. Most importantly, dog brains emit oxytocin when with humans—the same chemical that creates bonds of love and attachment in humans, and that is released in women who are lactating. . . So, yeah: your dog loves you to no end, and is really smiling when s/he sees you.

Philosophy:

Infinite Resignation: On Pessimism by Eugene Thacker.

Infinite Resignation: On Pessimism by Eugene Thacker.

This book has two parts: the first devoted to Thacker’s own comments on pessimism and the shortcomings and inherent failures of devising a philosophy of pessimism; the second devoted to “The Patron Saints of Pessimism” (at the section is titled)—a series of brief, bio/critical essays on Schopenhauer (of course—the Jesus Christ of misery), Nietzsche, Lichtenberg, Kierkegaard, Pascal, etc. In short, pessimism is an outlook allowing for precise pinpointing of uncertainties in others’ arguments, proposals, assumptions, etc. Pessimism is not, however, a method for producing a systematic philosophy upon which one can build, e.g., a method for living. That said, the first part of the book is often hilarious.

Naked Thoughts by Róbert Gál.

Literary, poetic, philosophical aphorisms, often funny (“The ambition of laboratory mice”), sometimes stoic (“A failure is a first draft. And a first draft needs no motives.”) or allusive (“Only things actually said can be passed over in silence”), Gál’s lines are compressed observations of life with almost haiku-like density.

Children’s Literature:

Vivaldi by Helge Torvund.

Tyra, young girl—at some point in elementary school, probably—with a rich emotional life and imagination, acquires a pet cat that, along with the her nascent love of music, elates an otherwise shy and uncertain psyche: alternately teased and ignored at school, where she remains silent, lost in her imagination. The book is beautiful, sympathetic, and illustrated in a way that capture Tyra’s spirit.

Dumpster Dog! by Colas Gutman.

A smart and funny story about a stray dog looking for a family: a neat trick, given that the territory covered here includes theft, kidnapping, and animal abuse. But all ends as it should, and young readers might be a little more street-wise as a result.

Fantastic Toys: A Catalog by Monika Beisner.

Fantastic Toys: A Catalog by Monika Beisner.

Beisner illustrates and describes 11 toys, how they’re operated or how they are played with. And they are indeed cool toys that kids (well, anybody, actually) would enjoy. How about a heated sheep toboggan that baa’s when squeezed by a rider’s knees? A glow-in-the-dark teddy bear for those frightened of the dark? You can almost hear the gears turning in the heads of young, proto-engineers as they take in these descriptions.

Cicada by Shaun Tan.

Is this really for kids? Maybe, like the the eponymous Cicada, I’m too close to retirement to see that part of the story from a child’s point of view, because the way Cicada’s employers treat him deepens and complicates the story’s pictures and tone. Tan does well in creating tales simple yet nuanced, tempering the sugary sentimentality that often spoils children’s books. Tan’s reality is hopeful and honestly earned.

The Water Spirit by Alexander Utkin.

Well-told, well-illustrated Russian folktales, with a big cast of characters: do-gooders, evil-doers, erring humans, angry spirits, generous spirits, crime, punishment, and everything in between.

Tyna of the Lake by Alexander Utkin.

The third installment of Utkin’s re-telling of Russian folktales. I don’t know the tales Utkin’s books have been based on, so I can’t evaluate his faithfulness to them. But in terms of making old folktales fun and exciting, Utkin does a great job of pacing and illustrating Tyna’s rescue of the Boy (from volumes 1 and 2) from the clutches of her father, Vodyanoy, the water spirit. One major difference between folktales and contemporary life: In the folktales, even bad guys honor their word.

The Curious Lobster by Richard W. Hatch.

An unlikely trio of eccentric, fussy creatures (Messrs. Lobster, Bear, and Badger) become friends and go on adventures. Often funny, always brisk and sunny (and well-illustrated), The Curious Lobster is similar to Milne’s Pooh, and Hatch’s observations, like Milne’s, are about character, friendship, duty, the ability to rise above the weirdness of others, and the ability to work together.

Graphic Novels:

Graphic Novels:

Reincarnation Stories by Kim Deitch.

Deitch is in top form in this book of interconnected stories. (And, yes, Waldo shows up.) From layout to storytelling, the book is fun to look at and read.

One of my hobbies has been reading nineteenth century novels, and they do it all the time. H. Rider Haggard sort of starts his books like, “I was sitting in my study, and suddenly this gaunt man was knocking at my window…” I don’t know, it’s just an interesting way to start a story, and to kind of palm it off as true is fun. I want to be a truthful person in this world, but it’s the thrill of being a pathological liar without being a pathological liar. –Kim Deitch, Interview in Comics Journal

Clyde Fans by Seth.

This is a story of the Matchcard brothers, who have picked up the fan-selling business begun by their father, Clyde. Nobody in this book enjoys their life or their fate: repression and resentment mark the yin and yang of their emotional lives. Apart from the downer storyline, the artwork and design are impeccable, and nobody better exploits the moods created by shadows than Seth, who works primarily with shades of grey—from blue-grey to olive-drab. Working with that simple color palette and a drawing style that harkens back to ‘40s- and ‘50s-style illustration (with a little Art Deco here and there), Seth literally illustrates the broad range of effects that can be achieved with just basic materials. If the storyline ain’t your thang, you can think of the book instead as a 500-page portfolio of design and technique.

MacDoodle St. by Mark Alan Stamaty.

A self-conscious, self-referencing comic strip blending Mad-magazine-like marginalia with deadpan humor and surrealist imagery in the telling of a shaggy dog story. A story told with the energy of an obsessive-compulsive outsider artist: the absurdly minute details, obsessively repeated, but each unique—dozens of characters, buildings, and settings, yet no two alike: the art of the snowflake, exhaustively traced in its infinite permutations. . . No wonder Stamaty was burned out after completing this story.

Parallel Lives by Olivier Schrauwen.

A series of interconnected stories that occur sometime in the future, told from the POV of somebody in the present communicating to the future (in the present of the future), and from the POV of people in the future trying to remember what their lives were like before endless space travel and gender-fluid hormonal balancing among all of the travelers. Schrauwen’s Parallel Lives is often funny while also questioning norms of time and gender.

Poetry:

Aug 9 – Fog by Kathryn Scanlan.

Based on entries from an 86-year-old woman’s diary over the course of four years, Scanlan condensed and re-arranged entries from this diary to create a fictional year in the life of an unnamed narrator, whose entries are terse and sometimes semi-cryptic, but all in the voice of the original diarist.

Vasko Popa by Vasko Popa.

Combines knowledge of folklore with affinities for surrealism and word play to create poems describing myths of imaginary conditions, often funny.

What’s in a Name by Ana Luísa Amaral.

Reminiscent of Szymborska: Blake’s universe in a grain of sand found at home, among family, friends, and lovers.

Art & Photography:

The Color Work by Vivian Maier.

The Color Work by Vivian Maier.

What percentage of Maier’s work has been scanned and document, and how much has been published? With a legacy of something like 140,000 negatives and positives and thousands of rolls of undeveloped film left behind, a mini-industry in Maier photography books, with few significant overlaps that I know of, how much more can we expect? “The Color Work” hints at far more yet to be seen: dozens of well-composed photographs that give the impression that Maier had—if not an unfailing eye—an eye that was more often acute than not.

The Photographs of Charles Duvelle.

Photographs and CDs: documentation of traditional, indigenous music from the eastern and southern hemispheres, as recorded by Charles Duvelle, who pretty much represents the face of Ocora, France’s prestigious label devoted to world music.

Route 66 by Thomas Ott.

While not the usual Twilight-Zone-esque tale Ott is probably best known for, Route 66 showcases his considerable technical skills as a scratchboard artists, illustrating views along the famous highway. Consistently excellent work.