I arrogantly recommend… is a monthly column of unusual, overlooked, ephemeral, small press, comics, and books in translation reviews by our friend, bibliophile, and retired ceiling tile inspector Tom Bowden, who tells us, “This platform allows me to exponentially increase the number of people reached who have no use for such things.”

Links are provided to our Bookshop.org affiliate page, our Backroom gallery page, or the book’s publisher. Bookshop.org is an alternative to Amazon that benefits indie bookstores nationwide. If you notice titles unavailable online, please call and we’ll try to help.

Read more arrogantly recommended reviews at: i arrogantly recommend…

THE FURTHER READING LIBRARY

THE FURTHER READING LIBRARY

Theater, dance, literature, music, and art are each represented in the first five volumes of the new Further Reading Library, “an ongoing series of books dedicated to forgotten ideas, overlooked accomplishments, and idiosyncratic world views” using “original documents, photographs, and primary source material.” For me, this amounts to a view toward the arts similar to Cabinet Magazine in its physical incarnation: eclectic, curious, nonhierarchical though appreciative of skilled craft, and open to exploring alternative proposals for producing and understanding any of the arts.

The Library is edited by Christine Burgin and Andrew Lampert. Christine Burgin is a publisher and former gallerist, Andrew Lampert an artist, writer, and curator.

Sound May Be Seen

Sound May Be Seen

Margaret Watts Hughes

Sound May Be Seen re-introduces us to the forgotten pictures created by the Welsh singer Margaret Watts Hughes, whose husband introduced her to Ernst Chladini, the German physicist and musician who discovered that the vibrations created by tones create distinct patterns on flat surfaces upon which a fine coating of sand has been added. Each vibrational frequency produces its own pattern. Startled and enchanted by this discovery, Watts Hughes began experimenting with the technique using a device she invented on which she coated a mix of semi-solid paints and other color-producing media. She discovered that she could produce a startling variety of images with her voice—images often floral-like, resembling daisies, ferns, fronds, tendrils, and seaweed-like plants. London’s Royal Society of scientists were intrigued, as were Theosophists, who were certain that Watts Hughes’s pictures revealed access to the metaphysical realm, the spiritual plane. Watts Hughes, a devoted Congregational Christian, had nothing to do with that, but her fame was far and wide.

When Watts Hughes’s pictures were rediscovered about a decade ago, in a Welsh library, they could for the first time be appreciated for their colors by an audience larger than that which relied on black-and-white newspaper reproductions, as they did at the turn of the 19th century.

I continued my investigations and slowly and gradually discovered that by singing certain notes into the eidophone [her invention] over the mouth of which the disc is placed. I can sing various substances, such as sand, lycopodium, or coloured liquids into certain figures. Every single note produced a figure in which the vibrations of the voice are recorded by clear and regular tones. According to the pitch, intensity, and the duration of the notes, however, the form of the voice-figure differs.

Clavilux and Lumia Home Models

Clavilux and Lumia Home Models

Thomas Wilfred

Born in 1889, the Dane Thomas Wilfred (née Richard Edgar Løvstrøm) was a proponent of a new art form he called Lumia, abstract shapes of various colors, perpetually changing, produced by a machine equipped with light bulbs, mirrors, colored discs, various buttons and motors, and sometimes keyboards, which projected swirling swaths of colors across walls and ceilings, the rhythmic flow of shapes and patterns rarely corresponding to the flows of music. It was not to be confused with devices such as Scriabin’s color-note organ for two reasons: Wilfred wanted Lumia to be appreciated for itself, by itself, and he didn’t believe in synesthesia (a neurological condition Scriabin had, in which different note tones corresponded to different color tones). To that end, Wilfred design, built, and tested a number of devices for spaces as large as auditoriums and as intimate as a home living room (those shown throughout this book). Home devices were designed to look like ordinary furniture while not in use.

The home devices did not allow users to manipulate the images. However, different parts of the device had different durations, so that, for instance, 51 hours might transpire before the piece repeated itself. (This predates by nearly a century visual works like Brian Eno’s generative 77 Million Paintings, which requires 400 years before the combinations restart.) A DVD showcasing Wilfred’s compositions would make an ideal companion to this book, which whets one’s appetite for more.

Although Wilfred preferred silent demonstrations of his Lumia devices, such as the Clavilux, musicians and their audiences craved accompaniment, including a performance of symphonic music in tandem with the Lumia, conducted by Leopold Stakowski. Because the images are abstract, in 1952 Wilfred was included in an exhibit of the new movement call abstract expressionism at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Lecture on Radium

Lecture on Radium

Loïe Fuller

Loïe Fuller (1862-1928) was an American dancer as obsessed with movement as she was light. Taken by the choreographic potential she saw in the phosphorescent glow that radium imbued materials with, she talked with Madame Curie a couple of times, as well as Thomas Edison, to discuss ways in which she could use the hidden light of radium to incorporate into her dances. Warned by both Curie and Edison of the profound dangers of radium, she developed a way to use the glow of fluorescent salts to douse her dance materials in. (She used up to 300 yards of satin for a single gown.) She could dance in the dark for audiences, her gown the only source of illumination.

Beyond the applications of phosphorescence Fuller imagined for dance (included in the book are schematic drawings she submitted for numerous patents she was granted) there are also her letters to a Captain Reinach during World War I, in which she describes ways to use lighting on the ground to confuse Germany bombers above. As a collection of documents regarding a particular choreographer’s ingeniousness in applying her skills and knowledge in innovative ways, Lecture on Radium makes a good case for Fuller. Sad to say, no color photographs of her dances are reproduced here, probably because her performances occurred before color film was common.

Some Stones Are Ancient Books

Some Stones Are Ancient Books

Richard Sharpe Shaver

Richard Sharpe Shaver, born in 1907, gained a measure of attention and a following in the 1940s when the editor of the science fiction magazine Amazing Stories, Ray Palmer, published some materials Shaver sent him. At the time, Amazing Stories published factual news items about the sciences, in addition to fiction, and encouraged readers to submit items of scientific arcana. This is what Richard Sharpe Shaver did. An otherwise itinerant worker, Shaver claimed to have discovered that many common rocks are actually ancient books waiting to be decoded. Which he managed to do. His Astounding manuscript included précis of these books, accompanied by a photograph of each rock whose plot was described.

Alas! photographic technology levels available at the time to Shaver were unable to read past the first, outer layer of the rocks, and he likens getting to better understand a rock by cutting it in half to cutting in half, say, the Nike of Samothrace—the structural elements are better understood but at the cost of the object’s integrity—and he was against it. Accompanying his “translations” of various rock surfaces was a mythology he developed (“discovered,” he would have it) regarding the ancient races of people responsible for them. Since he labels almost none of the photographs—his supporting documentation—, we’re essentially reading his interpretations of his own Rorschach tests. In which he believed.

Here is the text (typos included) paired with an image titled MICRO PHOTO OF AN AMAZON’S LEG:

We think of women’s boots as modern, actually the thigh high boot for women was high style in the Amazon empire long before the moon struck the earth. Here is a photo of an Amazon boot, which had a flap for riding out brush…much as chaps do today.

Think of Shaver as an outsider writer for whom rocks served as writing prompts, prompts fecund in imaginative impossibilities for an earthly prehistory passed down to us by alien predecessors, whose current hiding locations are known only to those who can read the codes. Perfect conspiracy stuff.

No Title

No Title

Richard Foreman

The poet Charles Bernstein noticed, on a visit to Richard Foreman’s loft, a stack of 3×5 cards in the bottom half of a tin. Each card had written on it, in black marker, a four-to-six word phrase: “Go twice around the clock,” “Believe in everything,” “Tomorrow is always better,” “Tell the world,” and so forth. Not quite I Ching-or Oblique Strategies-like in offering creatively ambiguous suggestions for arriving at solutions, nor quite koans to be puzzled out. Foreman says he doesn’t recall his motivation or intention for writing the cards. It may have been for a piece in which two or more actors took turns reading the cards. In the stack Bernstein found, there were 640 cards. No Title reproduces about 80 of them, as well as photographs of some of Foreman’s theater maquettes.

Slides of a Changing Painting

Slides of a Changing Painting

Rogert Gober

Primary Information

For about a year, between 1982 and 1983, I painted on a small board. Over this board I had mounted my camera, and as I changed the painting I would take slides of the process. So that in the end nothing remained but the photographic record of a painting metamorphosing.—Robert Gober, 1990.

Robert Gober’s summary of the work appearing in Slides of a Changing Painting is about all the text accompanying this book. At a painting a day—slowly, sometimes quickly, changing what is there—adding, subtracting, erasing, and modifying, scraping off, blacking out, and starting anew—the collected Slides is like watching a year-long movie (or abstract graphic novel) slowly unfold, dreamlike in its logic, imagery, and pacing. At the end, the only evidence of a year’s labor are the photographs taken during the project and the single board that received the paint. Like a Buddhist mandala meticulously designed from colored sand then destroyed, Slides also—in addition to creativity—embody the notion of transience and impermanence of life.

Ginseng Roots: A Memoir

Ginseng Roots: A Memoir

Craig Thompson

Pantheon

Cartoonist Craig Thompson’s memoir of growing up in a small Wisconsin farming community where he, his brother and sister and mother worked 40 hours a week for ten years (starting when Thompson was in fourth grade) tending to ginseng plants. At that time—the 1980s and ‘90s—Wisconsin was the world’s primary source of ginseng, its customers primarily from various regions of China. The boom ended just as Thompson’s secondary school education was ending.

For Thompson and his brother, the starting pay of a dollar an hour matched the going rate for the cost comic books. In Ginseng Roots, Thompson relates the personal and familial with ecology; Americana; American, Hmong, Korean, and Chinese histories; local and international economics; agriculture in general and ginseng roots in particular; a neuro-muscular condition in his drawing hand; and herbal healing via traditional Chinese medicine (non-acupuncture). Ginseng Roots is Thompson’s Moby Dick—to say that Thompson has written merely about growing up picking weeds during the summer is as accurate a summary of Ginseng Roots as it is to say that Melville’s Moby Dick is about a dotty sea captain with a thing for an improbably white whale: If that’s all there were to either book, they would make for much duller fare. But Ginseng stretches its own boundaries—it’s the work of a man who sees History not as something that happened to other people over there in some other century; History is what has contributed to making him, the nation, and culture he grew up in what it is, and continues to shape him, just as Thompson’s acts and creations shape someone else’s future.

Although Thompson reports his hand as severely damaged, whatever he did to overcome the limitations, the condition imposed upon him has made those limitations invisible: his brushwork is assured, confident, and clear, the mix of text and illustration cohesive and unobtrusive. The single nit I have to pick with Ginseng, however, is that the number of words and pictures required to tell his story lends his story a didactic quality that sometimes overshadows the narration’s momentum. That said, Thompson’s approach to his various topics makes them palatable in a way that a straight-up discussion of, say, agronomics, would make soporific. Recommended for school and public libraries.

Rebirth, Part One

Rebirth, Part One

Noah Van Sciver

Envious Editions

The first installment in a new memoir from Noah Van Sciver, focusing on his relationship with his oldest brother and his trajectory from idealistic fine artist to embittered cartoonist. The drive, self-awareness, and conscience of Van Sciver’s avatar make his all-too human errors forgivable when they come in conflict. Comic relief comes in the form of self-doubts and second guesses, and stubbornness over the wrong things.

LA CRÈME DE CRUMB!

LA CRÈME DE CRUMB!

Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, Dan Nadel, Scribner

Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, Dan Nadel, Scribner

Existential Comics: Selected Stories 1979–2004

R. Crumb; Dan Nadel

David Zwirner Books

Dan Nadel’s biography of cartoonist Robert Crumb is unlikely to be equaled or surpassed anytime soon. Having Crumb’s full cooperation with writing the biography meant access to the diaries, sketchbooks, letters (sent and received), and drawings Crumb has been keeping since he was 15—thousands of pages of archival material, supplemented with Nadel’s interviews with the living members of Crumb’s family and circle of acquaintances. It is entirely to Nadel’s credit that he sustains a clear through-line throughout the 400+ pages of narrative—describing Crumb’s peripatetic life as a child and adult and, as a successful artist, a densely populated love life comprised of a wife, two longstanding girlfriends, and countless one-offs.

Robert Crumb’s family was seriously dysfunctional: various levels and types of mental illness, violence (parent on child, parent on parent), dependency on prescription pills and alcohol, and general inability to socially cope. (For instance, Sandra, the youngest of the clan, routinely drank herself to sleep by age 13.) Although Crumb’s father, Chuck, was in the marines for over 20 years, he never rose above the rank of sergeant. Chuck’s frequent reassignments was one cause of the family’s frequent moves. The other factor, leading to just about as many moves, was noise complaints from neighbors about the yelling between Chuck and his wife, Bea, a prescription Valium addict since the early 1950s, accompanied by occasional bouts of electroshock therapy.

In the chaos of their childhood, the five Crumb children (Robert was the second oldest) took salvation in comic books, reading them and creating them, herded by the oldest brother, Charles. Under Charles’s strict command, the five kids produced a monthly comic book for a couple of years, just for their own entertainment. Eventually, the command performance came to an end, but the brothers Robert and Charles continued cartooning individually and together, producing a couple dozen pages a month of their own stories. By the time Robert Crumb, fresh out of high school, applied to draw cards for American Greetings, he already had thousands of hours of cartooning under his belt.

At American Greetings, his talent was quickly recognized, and he was promoted to draw the company’s more expensive line of cards. (His boss was Tom Wilson, would go on to create the successful syndicated comic strip, “Ziggy.”) Still, this kind of life was, um, not in the cards for Crumb, a job that provided anodyne images to illustrate a small range of human conditions, moods, and rites, for commercial profit. Hearing the call of San Francisco, he left American Greetings and moved out there. (However, for years afterward, Crumb continued take anonymous assignments for American Greetings, wherever he lived, to supplement his meager income.) He was introduced to marijuana and, more critically, LSD, which he credits for creative and emotional breakthroughs and whose after-effects encouraged him to cultivate the visual style that immediately identifies an illustration as one of his. Based on the strength of only two published pages in two separate underground newspapers, he was offered a book contract from Viking, the prestigious mainstream publisher. At the same time, bootleggers around the world were illegally reproducing “Keep On Truckin’” logo and images, as they were his character, Mr. Natural. Attorneys were hired, and Crumb gained a modicum of control over his creations.

By the early 1970s, he published upwards of 160 pages a year, including work for Zap, the comic book collective he founded. By the mid-‘70s, the underground comix scene was tanking, and Crumb was burned out.

Existential Comics: Selected Stories 1979–2004 collects lesser-known strips drawn by Crumb between 1979 and 2004. This trove of 25 years’ worth of some of Crumb’s finest work show that, although he was no longer creating genre-busting works, he had reached a high point in draftsmanship, storytelling, and (in his biographical and historical pieces) editing. Whether with a pen, quill, or brush his style is distinctive and confident.

Existential Comics: Selected Stories 1979–2004 collects lesser-known strips drawn by Crumb between 1979 and 2004. This trove of 25 years’ worth of some of Crumb’s finest work show that, although he was no longer creating genre-busting works, he had reached a high point in draftsmanship, storytelling, and (in his biographical and historical pieces) editing. Whether with a pen, quill, or brush his style is distinctive and confident.

In a look back at the ‘60s he’s thankful for his sexual awakening, but is ambivalent about the chaos it introduced into his life, along with numerous LSD trips on powerful acid. He muses over his “trouble with women” and the belittling sex play with them that also encouraged his dismissive thoughts of responsibility to them. In another confession, his mid-life crisis seems more like a chance to wallow in the sort of self-pity indulged in only by those who have achieved a measure of world-wide fame.

In Crumb’s choosing to tell the stories of, for instance, diarist James Boswell, blues singer Charley Patton, SF writer Philip K. Dick, or case studies from Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis, Crumb is interested in those psychological points where his and their obsessions cross: LSD revelations, weird sexual impulses, pursuing intellectual pleasures, and more. In his take on a few diary entries by a young James Boswell, for instance, you can see the appeal to Crumb of this scion of wealth, whose tastes 200+ years ago accord well with Crumb’s own ideal: Days filled with convivial, learned conversations with kindred spirits, enhanced by alcoholic spirits; nights filled with debauchery and women of easy virtue.

Printed on heavy stock paper, the print quality allows for the quality of Crumb’s visual expressions to shine through. Telling the story is as important for Crumb as showing the story, as demonstrated by his long excerpt from Psychopathia Sexualis, in which Krafft-Ebing’s straight-faced medical narrative is juxtaposed with examples of how the various patients’ behaviors looked in private (masturbating with women’s shoes, for instance) and under sober examination by members of the medical profession—straight-up absurdity placed under conditions of “normality.” One man’s quest to better understand himself amounts to a quest to figure out others—and why they’re all so fucked up. Existential Comics is strongly recommended for readers unfamiliar with Crumb in reflective mode.

Readers already familiar with Crumb’s personal life will notice I haven’t said much about his love life, which was complex and promiscuous yet fundamentally a series of relationships among consenting adults, which usually began with Crumb getting a piggyback ride from a woman to test the strength of her thighs, calves, and buttocks. The relationships led to unconventional living arrangements among the adults and, in the case of his son, Jesse, neglect.

Although the underground comix scene peaked two generations ago, Crumb kept busy over the next 50 years (as Existential Comics shows), his general low profile brought attention to with the release of a documentary film about him (which won numerous awards) and, at age 66, the release of his illustrated Book of Genesis, in which every verse is given its own picture, in a straight-up, sober-minded presentation of Genesis, internal contradictions and all (with some of the Bible’s many sex scenes presented implicitly rather than explicitly). Low profile or not, by this time in his life, Crumb was able to fetch a $250,000 advance for his efforts.

Anybody interested in Crumb’s art or in cultural figures from the ‘60s and ‘70s will do well to read Dan Nadel’s Crumb. For that matter, any young person interested in what dissent used to look like before it was coopted by capitalism as just another lifestyle choice, as well as the DIY spirit that animated much of the punk energy of the late 1970s should put Crumb at the top of their TBR pile.

Q&A with Dan Nadel

In addition to writing the new Crumb bio and editing Existential Comics, Dan Nadel is also the curator-at-Large for the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, has served as editor and publisher The Ganzfeld and PictureBox, and has edited and curated dozens of books and exhibitions related to popular and non-traditional visual arts.

What in your background appealed to Crumb, suggesting to him that you could deliver the type of honest assessment he was looking for?

Robert agreed to my writing the book precisely because of all my work on other cartoonists and the history of comics. He didn’t want to have to educate his biographer on his medium. So, there I was. Relatedly—PictureBox and the Ganzfeld and all that—I feel like I got a really good understanding for how an idea goes from inception to bookshelves, and how it can feel to be on all sides of that equation. That means I could sympathize with and envision what everyone was going through getting Crumb’s work out into the world. I also saw firsthand how influence can work between artists, the tendency to want to be both inside and outside a world, and the compromises and strangeness of moving between worlds—underground, gallery art, zines, etc. I’ve seen all that up close. So, the “history” within Crumb was/is familiar to me.

For the Existential Comics anthology—which is a greatest hits of Crumb’s storytelling abilities from the first 25 years after the initial rush of his fame had passed—had you considered including pages from his youth—including collaborations with Maxon and his siblings—and his greeting cards? Their contents are described so tantalizingly in the bio, that I had hoped to see them represented in the companion anthology. What were your criteria for inclusion in Existential Comics?

The idea here is that Robert Crumb is an artist whose primary legacy is his work in comics. Ironically, with the exception of The Book of Genesis, that work is almost entirely out of print, or published in a way that makes it difficult to access. So, I wanted to put together a book that would offer indisputable proof of Robert’s truly incredible work in the medium. And I wanted the book to be accessible, meaning 200 pages or so. I wanted people to want to read it like they would a well-assembled book of short stories. Which I hope it is.

To do that, it not only needed to be 200 or so pages, but needed to be more or less in a single aesthetic mode. I didn’t want to jump between the balloon tire work of 1968 and the realism of 1985. I wanted people to stay with Robert on this particular journey. So, I stuck with his cartoon realism of 1979-2004, which really is a 25-year-span in which, as I write in the introduction, he explores history, biography, spirituality, and autobiography, among other subjects. The idea was not a comprehensive Crumb “best of” or a direct companion to my biography, but a look at this concise period, something to hand to anyone wanting to know just why this guy is so great.

There will be other Crumb reprint projects down the road; this was the book I wanted to do first. As far as greeting cards, juvenilia and Maxon Crumb: Max has a few books of his own. I hope someone will publish a collection of Robert’s greeting cards—that would be great. And likewise, his juvenilia. But as I said, I had specific goals for the book that became Existential Comics.

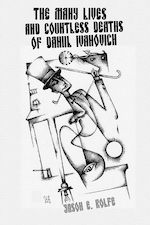

The Many Lives and Countless Deaths of Daniil Ivanovich

The Many Lives and Countless Deaths of Daniil Ivanovich

Jason E. Rolfe

Black Scat Books

Jason E. Rolfe’s The Many Lives and Countless Deaths of Daniil Ivanovich is (mostly) a collection of short stories in the manner of the Russian absurdist Daniil Kharms and about the imagined life of his creator Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev (Kharms’s real name), a low-level functionary in a bureaucracy run along inane premises:

Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev first learned of his death while at work. He had spent the first three hours of his day writing forty-three reports—the same forty-three reports he wrote every day—and the next three hours filing them. Between the fourth and fifth hours he paused for a brief lunch. It was during this pause that Daniil read the memo announcing his death. There were no details, merely a sentence stating that Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev had died, and that no replacement would be necessary as the reports he wrote, filed and shredded on a daily basis, were superfluous.

Kafka seems a kindred spirit of Yuvachev’s in dealing with the soul-crushing inanities of alienating labor. And anybody who’s had a desk job will recognize the symptoms of bureaucratic cancer that have not abated (and perhaps only increased) during the past century—the production of useless reports, endlessly winding corridors of look-alike offices, and dog-like servility in the performance of useless tasks. The longest of The Many Lives’ collected absurdities is a 40-page tribute to other Russian writers of the early 20th century—Gogol and Ilf and Petrov in particular—in a shaggy-dog story about finding the lost nose to a statue of Gogol, involving stolen jewels, a monkey, and obscure Russian civil infractions. An often-funny collection of stories whose appreciation does not require familiarity with Russian writers.