Boofland and Low-Fi Detroit

Boofland Babylon was a 2015 art installation by Cary Loren and Michael Zadoorian, proroduced by the Kresge Foundation and shown during ART X at MOCAD in 2015. The following year the installation travelled to Lille, France as part of the Lille 3000 festival.

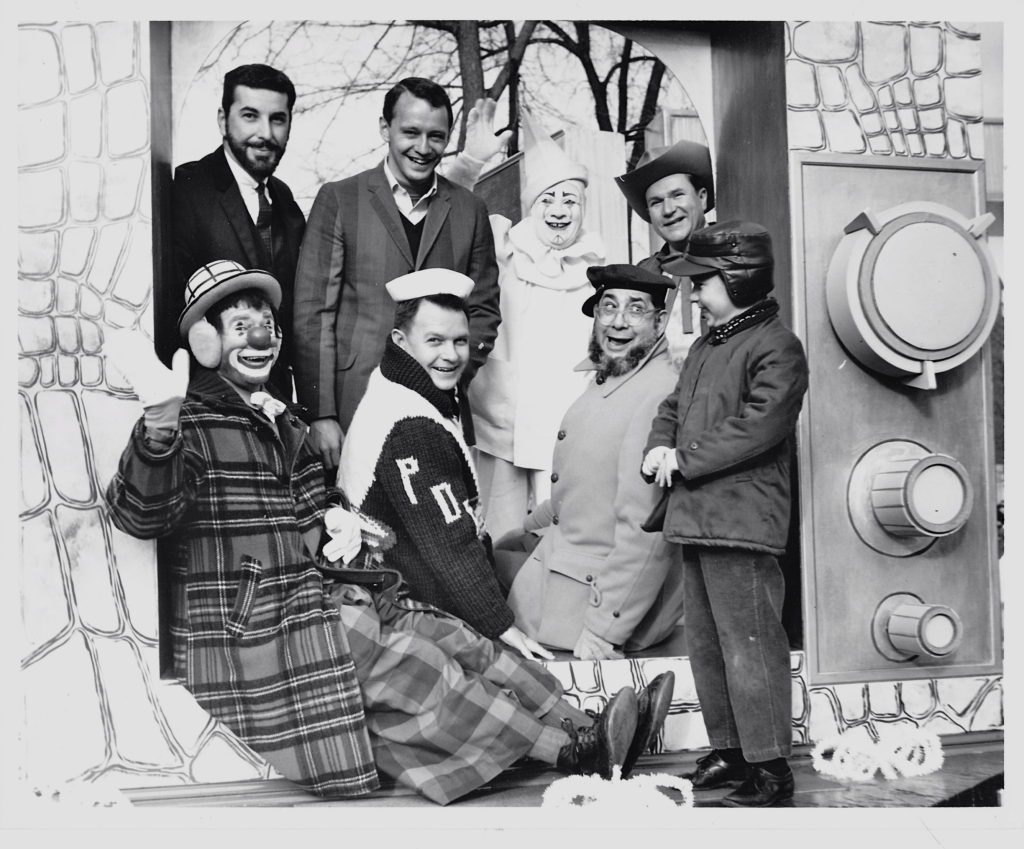

The origin and inspiration for the display was a photograph taken by Michael Zadoorian’s father Norman during the J.L. Hudson’s Thanksgiving Day parade of 1962. The photo depicted a giant sculpted television set with Michael Zadoorian at age five, standing inside the TV among a motley group of Detroit children’s television celebrities, including; Captain Jolly, Poop-deck Paul, Milky the Clown, Ricki the Clown, Sagebrush Shorty, and Canadians Larry Sands and Jerry Booth who created the Boofland show, an alt-universe of puppets, giants and royalty who lived at Jingle-the-Jester’s fantasy castle.

Jingles the clown with Herkimer Dragon and Cecil B. Rabbitt puppets on Feb. 11, 1960. (Windsor Star)

Boofland was a cheap children’s variety show of sing-alongs, puppets, cardboard castle sets, starring Jingles, a balladeer jester played by Jerry Booth. The show had a surrealistic set with puppets as local natives, slightly deformed and sad creatures. It was a parallel world to the Soupy Sales show, produced in the early sixties and utterly mysterious and mesmerizing. A day wasn’t complete without watching Boofland. The show was totally out there; a castle floating in the clouds, a whimsical land of giants, dragons, and magical rabbits residing in a cardboard universe of paper-machè and glitter. An off-kilter dream world with each show’s episode ending with a gloomy sing-a-long and loyalty oath:

“Oh Boofland, my Boofland/ Let us always sing/ And have some fun with Cecil B./ Herkimer and Jing/ No matter how big I get/ No matter where I go-go-go/ I’ll always watch my TV set/ For the Jingles show.”

Boofland was also a physical vacationland, a fantasy village founded by Jerry Booth in 1960, similar to a low-budget Disneyland situated on the edge of Windsor Ontario in Canada. It was a park with rides and a miniture train, but without any real public support it closed and after six months it burned down in a fire. Boofland was cancelled by CKLW in 1961 ending its five year run. Booth moved on with a bit roll in the Canadian children’s show “Fun House” and played Bozo the clown for a while. He moved on to Los Angeles where he became a salesman and died in 2017 at the age of eighty-two.

In the ’50s and early ’60s, local boomers were raised on a diet of early morning and afternoon cartoons; Popeye, Tex Avery, Looney Tunes, Flash Gordon, Tarzan, Robin Hood and Three Stooges episodes aired daily, hosted by all major broadcasters. Wixie in Wonderland first aired in 1948 on WXYZ-TV and was one of the first shows nationwide to screen cartoons, and starred Marv Welch as Wixie-the-Pixie, who in the evening was a local X-rated night club entertainer. Wixie was the first host of a variety show aimed at children, a trend that quickly spread across the nation.

In early ’60s Detroit, Soupy Sales was king of kid’s TV. His show was pure vaudeville, with borscht-belt humor and an odd assortment of character sidekicks. Giant dog puppets White Fang and Black Tooth, and Pookie the sassy Lion were superbly performed by Soupy’s stage hand Frank Natasi. The show had a subversive edge and a conspiratorial tone shattering the fourth wall. If Soupy told you to have tomato soup or a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for lunch–that’s exactly what you’d have.

In the late fifties on Saturday nights at 11:30 PM, Shock Theater would begin with creepy Doctor X reciting, “Lock your doors, close your windows, and dim your lights. Prepare for Shock.” Then his face would dissolve into a screaming skull or hypnotic eyeball to begin the monster film feast. The skull and optical effects was frightful and a a few years later, Detroit was home to Morgus the Magnificent, a mad scientist who showed horror films and was also the afternoon weatherman. Detroit airwaves were filled with horror and cartoon hosts -the unsung heroes of low budget fare we loved and watched obsessively.

Photographer Norman Zadoorian at the corner of Junction and West Vernor Highway.© estate of Norman Zadoorian

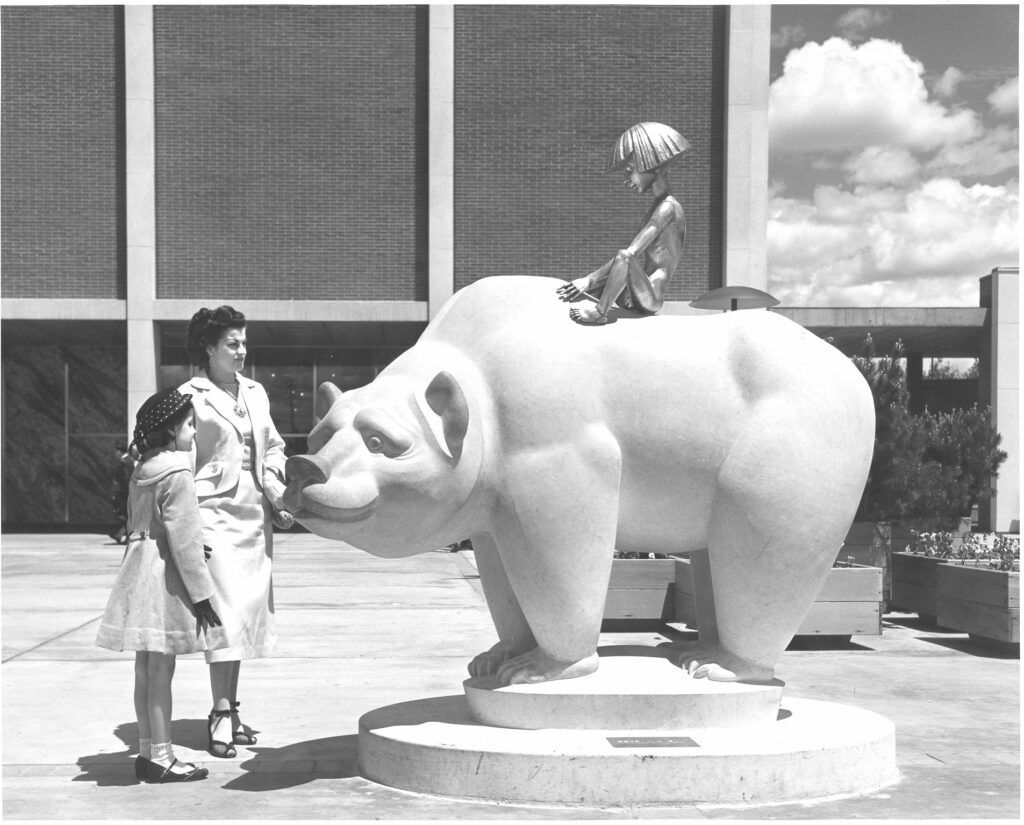

Marshall Fredericks Boy and Bear sculpture at its first home in the Northand shopping mall, photo ©estate of Norman Zadoorian

The Boofland Babylon foundation was not only lowly TV culture but also the landscape of Detroit; the scenic views of modernism captured by Norman Zadoorian’s square format Rollieflex. Northland, the first suburban shopping center, shot by Zadoorian on opening day in 1954. Other Zadoorian subjects Bob-lo Island amusement rides, Detroit’s skyline in psychedelic color and the strange atomic-age restaurants, and lonely street shots of theaters, snow-covered sidewalks, and curvaceous finned autos. Other Zadoorian subjects covered included the J.L. Hudson’s Thanksgiving Day parades, a modern car wash, and nameless automats and diners.

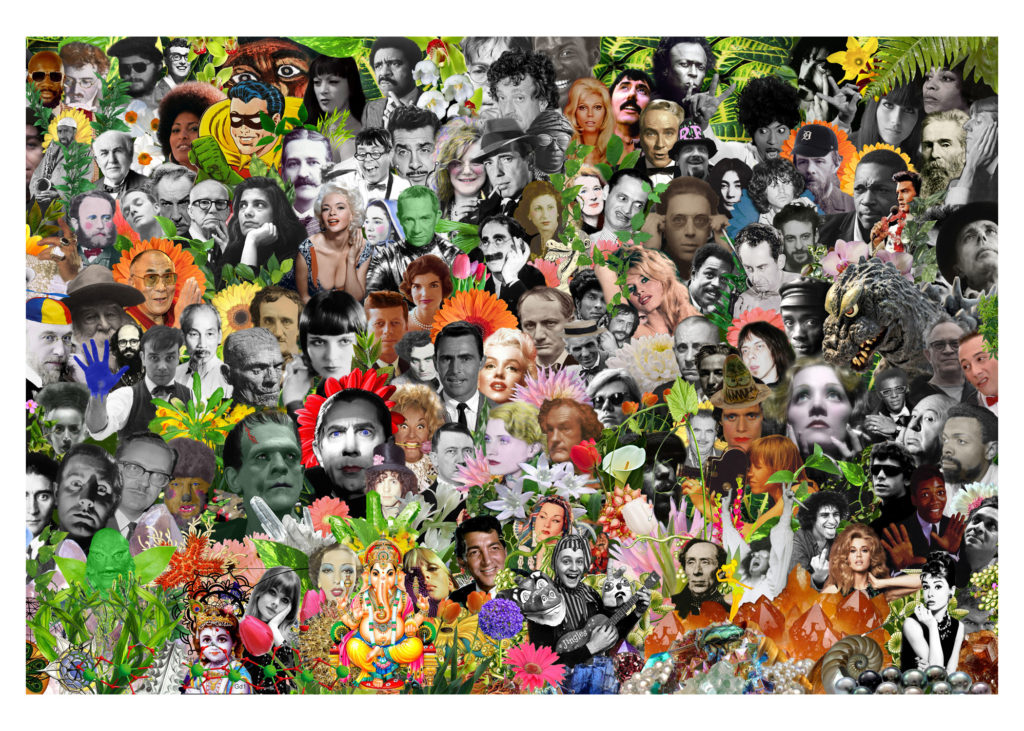

Boofland Babylon was a scrapbook of regional memory, that took on the physical structure and form of the epic Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album. Life sized figures of Detroit icons were printed, cut out and mounted on foamcore. The fugures served as a tableau gathering of low pop-culture. Life sized images of John Lee Hooker, Milky the Clown, Mayor Coleman Young, Ray Johnson, John Sinclair, Fred “Sonic” Smith, Morgus, and Sir Graves Ghastly stood mashed together with National figures like Nancy Sinatra, Captain Beefheart, Emma Peel of the Avengers, Andy Warhol, Vampira and Tor Johnson, Batman, the Wicked Witch of Oz and her flying monkeys. In front of them all stood the lifesized figure of Norman Zadoorian, a camera hung around his neck and a cigarette in his mouth. He stood as the guardian of suburban dystopia. Another 20′ banner hung behind all the standing figures and multiplied this hagiography with a crowd of several hundred other legends, mimicking and uping the ante on the Beatles cover, a lonely heart’s club band for the underground.

Zadoorian’s photographs were a “hidden exhibition” behind the cut-outs of pop culture. The exhibit was entered from the side or front and discovered slowly. No angle permitted a complete view of the display. Zadoorian’s dream world became the backyard suburban barbeque we now call Tiki culture; a mixture of Martin Denny lounge music, rum drinks, and South Pacific pop-Primitiva. A suburban utopia created from the destructive power of World War II, the South Pacific and the Atomic bomb.

Zadoorian’s photography was presented as a pyramid, like steps along the Aztec avenue of the dead: Teotihuacan, the sun pyramid of promise beneath the valley of industrial waste. Foundational and ancient memories hold up the spiritual, non-material, and imaginative banners of the past and future. The Thanksgiving Day banner sits at the top of the pyramid, an innocent childhood vision of kitsch-wonderland. The banner is part castle/Boofland set and part life-sized TV; one could walk through and into, merging with these magical heroes into a vision more real than reality.

These memories are transporting like Proust’s ephemeral ‘madeleines’, a symbol of the past that rises unintentionally as the perfume of an imagined dreamland. Only a few photographs and perhaps seconds of screen time of this artificial reality exist. Each of the minor celebrities were huge in the minds of children, but they were unpreserved and erased, too ephemeral and briefly lived to matter. A dragon for the mind. Nothing was saved of these media-hosts except their memory in aging boomers. Boofland Babylon became a narrative to preserve these figures of impermanence.

The Sargent Peppers figure concept was attached to a sound field created from commercials and sound samples from the ’50s-’70s, wired by a random computer program created by sound wizard Leith Campball. Sound played randomly on small hidden speakers placed beside the cut-out figures. The display also had two supplemental vitrine displays of childhood collections that drew on memories of growing up in 1960s Detroit.

Zadoorian and Loren expanded their thoughts about Boofland Babylon in a small booklet containing several short essays, a self-interview along with a small gallery of images by Norman Zadoorian. The physical and visual work of the installation evolved from talks and meetings covered in the texts. The book was published during the Art X exhibition in 2015, and can be downloaded as a free PDF file at: BOOFLAND BABYLON GUIDE BOOK V5.

The Nature Banner or Summer on Cold Mountain

“The moss is slippery, though there’s been no rain

The pine sings, but there’s no wind.

Who can leap the world’s ties

And sit with me among the white clouds?”

–Gary Snyder, Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems

During the summer of 1969, Loren hitchhiked with his friend Tim Burton to the northern tip of Michigan at White Fish Point — a desolate rugged area on the shores of Lake Superior. They camped on the beach and awoke to a breakfast of fresh blueberries growing in the sand. Hiking through miles of a birch-tree forest and giant ferns they finally met up with Tim’s older brother Eric. The guidebook on that trip was Gary Snyder’s Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems, a manual for buddhist meditation and solitude.

During a night of cold rain they dragged their sleeping bags into Eric’s station-wagon. Something began shaking the car. A metallic scratching across the hood. Moments latter, Eric and his girlfriend pounded the door to let them in. A black bear attacked their tent and was just outside the car.

Watching the Milky Way for hours, shooting stars streaking in space. The group followed Route 66, searching the trail of Thoreau’s wildness and the highway west. Camping cross-country there was a week long stop at Lake Solitude, a seven mile hike to the center of the Teton mountains. Cold Mountain was a magical summer.

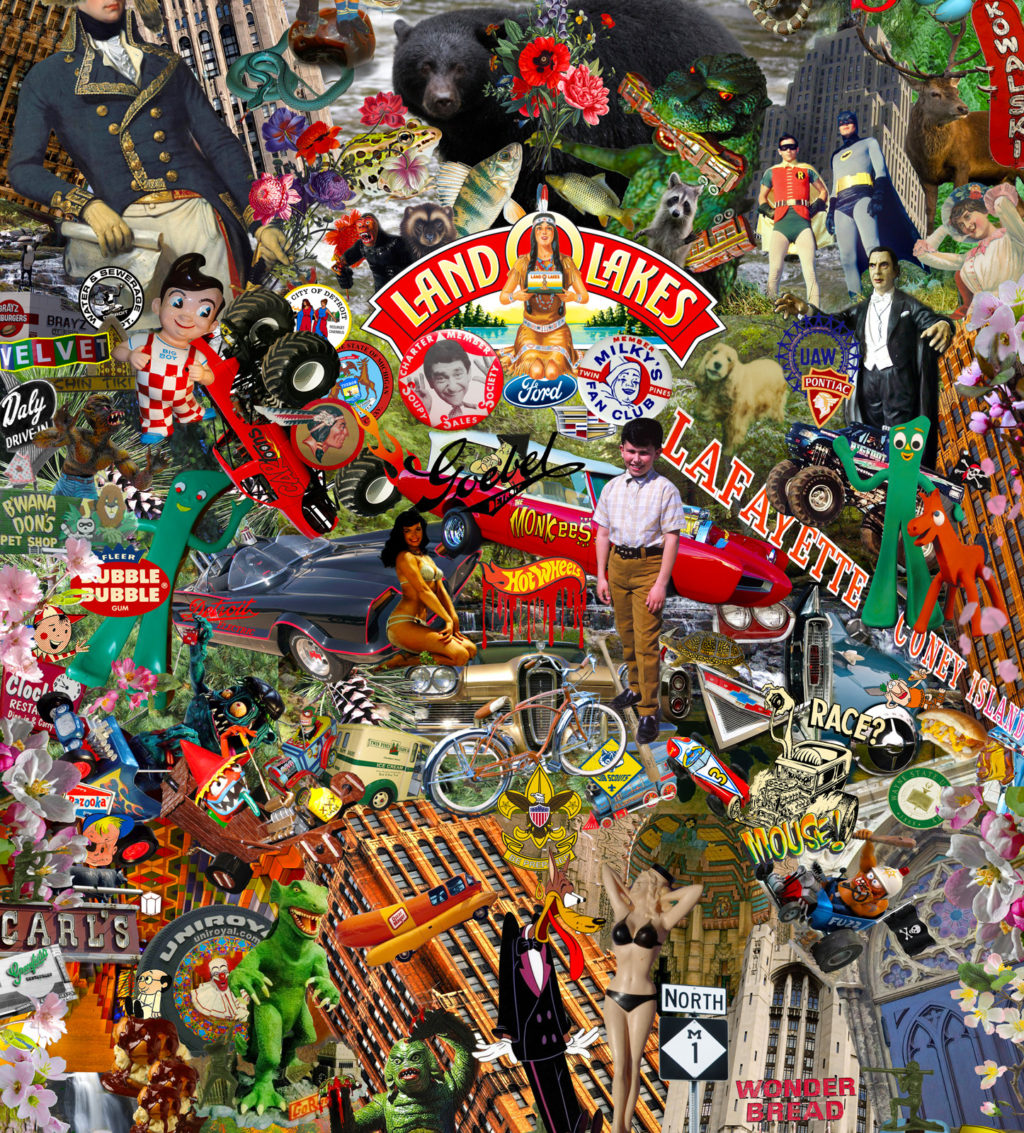

The central image on the nature banner illustrates Cold Mountain, a group portrait at a road-side feast of corn and plums. The white birch forest re-created in the background. The Black Bear, a symbol of destruction and chaos, nature run amok. Water and earth surround the banner and cascade over early memories; monster model building, Mighty Mouse cartoons, The Batmobile, The Addams Family, Vernor’s ginger-ale and Jane Mansfield water-bottle mysteries. The Faygo waterfall comes to rest at the Detroit river, where Beenie and Cecil finally arrive home.

The sides of the Nature banner depict the food, nourishment and landmarks that helped sustain us. The Clock, B’Wana Don’s pet shop, Faygo and Towne Club sodas, Kawalski brats of Hamtramck, Wig-Wam, Bray’s Burgers and other sacred spots on our map of time’s past.

A portrait of Michael Zadoorian is juxtaposed beside the Monkee-mobile, a Pontiac GTO modified for the 1966 Television show band the Monkees. A large part of Zadoorian’s youth was also spent camping. His family trailer is depicted in the top right corner of the banner, cruising by Route-66 roadside attractions that would inspire his later writings, especially the novelThe Leisure Seekers, later made into a motion picture staring Helen Merrill and Donald Sutherland.

The Spirit banner or A War in Space

“The soldier above all others prays for peace, for it is the soldier who must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war.” –Douglas MacArthur

The Fire Spirit banner is pure imaginary play, cartoons, radio airwaves, comics, airships, night sky, space exploration, horror, objects and characters floating, an imaginary, non-physical heaven and hell. WWII firefights and bombing raids are mixed beside a Buddhist nirvana. Backgrounds were made of gumball tokens, marbles, toy cars, other collections. Hypnotic sound waves and radio call letters, the physical made spirit. Comicbook characters and TV cartoons became spirit centers. Atom Ant, Mighty Mouse and other ‘flying’ creatures share air space with angels and Buddhas.

The Spirit banner contains radio transmissions and deals with electricity. Detroit Edison was Norman Zadoorian’s employer, represented by the “Sparky” logo in the middle section. Mid-century electricity charges the spirit into rock ‘n roll.

The pillar of light that contains creativity and imaginary games, morphs into the light that develops modern warfare and industry. General MacArthur is seen stepping onto the beach of Leyte, Philippines, the island is on fire, and the site where Norman Zadoorian was wounded and sent home.

Some of the dark and more disturbing photographs by Zadoorian were taken on the streets of Detroit, soon after his army discharge. At the bottom of the Spirit banner bombs litter the sky bursting with cartoon characters, figures of pure imagination amid a battleground violence. A post-war ‘comic’ landscape emerges from bombs and the hell of war. As Zadoorian nursed his wounds he photographed the Detroit streets searching for answers. An inheritance of media overload and absurdity was handed to us by the greatest generation–a gift to block out the dark shadows, given by those who battled to defeat fascism and the tyrant Adolf Hitler.

–Cary Loren, 2015, revised 2019

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8otr8A6dNEQ&t=219s

Do you know where I can find milky the clown show? My mom dance on his show before

Don’t know where you can find Milky the Clown except on Youtube. I do remember Jingles flying down my street, Morris Drive, on a hot Windsor day in 1960 in his miniature red fire engine to pick up Lisa Priserry, who had won a contest and was to appear on the “Jingles in Boofland” show. We waved and yelled “Hi, Jing!” I was one of the few kids to have visited Boofland before it burned down. Sorry to hear of Jerry Booth’s passing in 2017.

Pretty sure it was White Fang and Black Tooth, not vice versa

Thanks Joe! Correnction made.

Does anyone remember the complete opening dialogue on Jingles in Boofland? It went something like: Away beyond the Ishcabol and across the Caspian Sea, there’s a place called Boofland where very soon you’ll be…