The Shining Moon, the Dead Oak Tree, Nights like This Appeal to Me. (1)

The Shining Moon, the Dead Oak Tree, Nights like This Appeal to Me. (1)

By Ben Schot

The comeback is characterized by a temporary disappearance, after which the return can be celebrated with all due. It is a variation on the resurrection, on rising from the dead, which has a long history and has been translated into countless myths, fairy tales, rituals and artefacts. From Lazarus to Iggy Pop, from Elvis to Martina Hingis, many are acquainted with it. There really is life after death, certainly in art.

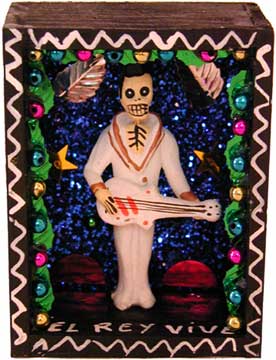

Amongst the knickknacks on our mantelpiece is a small box, containing a crudely modeled Elvis figurine. We received it at some point as a gift from a friend. The cheerfully decorated box was made anonymously for the Dia de los Muertos on November 1st and 2nd, when Mexico celebrates the dead. We know it is Elvis because of the white, open-necked jumpsuit, the greased-down black pompadour and sideburns and the white acoustic guitar. Written at his feet is the text, “El Rey Vive”. But the ironic character of the message is evident in the grimacing skull where Elvis’s face should be. The King is alive, but death rules. Let us not forget who is in charge here.

Rising up from the dead is a motif that is deeply anchored in our psyche. Throughout the ages and spanning widely diverse cultures, fantasies of resurrection have generated a plethora of artefacts, rituals, fairy tales and myths. In just that little box over our fireplace, Aztec and Spanish Catholic cultures are joined with American pop. What all these resurrections have in common is that they are all self-contradictory representations that both recognize and deny death.

Death exists, but it is not definitive, and therefore death does not exist. If we are to believe the psychoanalyses, resurrection fantasies are for that reason variations on a universal theme that can be traced back to our ambivalent longings for both immortality and death.

A condition of non-existence, a symbolic death, also precedes the comebacks of the living.(2) It might be a period of decline, illness, old age, addiction or another comparable cause for people to lose status and be forgotten. Rising up out of that situation is often celebrated in terminology that is reminiscent of a return from a mythological underworld. Comebacks are in fact mini-myths. The American actor, George Clooney, thus recently “climbed out of a deep pit”, tennis star Martina Hingis is as though “reborn”, and the American cyclist Floyd Landis made a “miraculous” comeback in the Tour de France (even if it later proved less miraculous than people had imagined). Death, that grimacing king in his white jumpsuit, is all-powerful, and every victory we enjoy over deaths “even though it can only be a symbolic victory” is firmly grasped, in order to sate our desire for immortality.

Sometimes, however, the comeback fails to happen, and there is only the symbolic death. One example is Syd Barrett. Beginning in 1972, when Barrett retreated from public life into his mother’s house for good, countless attempts were initiated to motivate the original leader of Pink Floyd into making a comeback. All to no avail. Even a lucrative offer from a recording studio could not awaken the songwriter from the creative death brought on by too much LSD. Barrett’s comeback kept postponing itself farther and farther into the future, to finally dissolve into thin air. With the passing of the years, the formation of the myth no longer focused on his impending return, but on his silence, a silence far more genuine and touching than the demonstrative silence with which Marcel Duchamp enveloped himself during his lifetime. (Das Schweigen von Marcel Duchamp wird aberbewertet, as Joseph Beuys rightly concluded in 1964.)

Syd Barrett’s lifelessness had already assumed mythical proportions when, a few months ago, he actually died. His physical death in fact no longer made any difference. A comeback was unachievable while he lived, had even become undesirable. The vulnerable Barrett had become a symbol both for eternal youth and for endless oblivion. Sleeping beauty on acid was “long gone”.(3) Coming back was out of the question. This is quite a different story than the posthumous comeback with which Duchamp crowned the self-fabricated myth of his person and his art, and with which he had made his early deposit on immortality.Etants donnes? Non, merci, astronomy domine.(4)

The Van Winkle Museum

In 1819, the American writer Washington Irving published his adaptation of the Karl Katz fairy tale, previously immortalized by the Brothers Grimm. Irving’s Rip Van Winkle is about a villager in the Catskill Mountains, north-west of New York City, who secretly tastes a magic potion and falls asleep. He wakes up twenty years later. When he returns to his village, he finds that his wife and several of his friends have already died. Moreover, the political situation has undergone drastic changes. Where Van Winkle’s village had once been under the rule of England’s King George III, it was now part of George Washington’s United States. He had slept right through the American War of Independence. Not that this made a lot of difference to the good-hearted, but lazy, Rip Van Winkle. Now that he was finally liberated from the scolding of his wife and could live out his old age in peace, he had all the time in the world to devote to his favourite, if unproductive pastime: sitting on a bench reminiscing about the past. His temporary death had brought him nothing but liberation. In America’s utilitarian culture, the name of Rip Van Winkle has assumed negative connotations. He is a symbol of those people or institutions that are unaware of their changed environments and have consequently become anachronisms.

Museums should adopt “Van Winkle” as a nickname: Boijmans Van Beuningen Van Winkle, the Stedelijk Van Winkle Museum, the Van Abbe Van Winkle. It sounds chic, too. Instead of giving in to unrelenting political pressure to find more ways of connecting to our consumer society, every museum should stand up for the right to devote itself to no other objective than to sleep, to dream, to look back and to offer its visitors a bench on which to do the same. A museum is by definition an anachronism. The collections for which museums are famous are comprised of objects that have been removed from the economic circuit. For this reason, a museum cannot be at the centre of contemporary life. Museums are rooted in a cult of the dead and the heroic: Jeroen Bosch Vive, Max Ernst Vive (all right, all right: Duchamp y Beuys Viven, too.)

Now that the honourable distinction between museums and commercial enterprise has been almost entirely eradicated, the financial success of any given exhibition is more crucial than ever. It is a success that in the first place depends on the publicity it generates. Therefore, it is not surprising that more and more frequently, museums are commercially exploiting what is in fact their cultural function: the cult of the dead and the heroic. As a consequence, in the publicity for retrospective exhibitions of still-living artists, we regularly find the word “comeback”, or some other reference to a resurrection, even when there really is none. One example is the recent publicity concerning the work of Ira Cohen. With his hallucinatory photographs and films, his poems and his fragile publications, Cohen has been a trend-setting counterculture artist ever since the 1960s, and he has worked, virtually without interruption, all this time. But in the publicity for several of his exhibitions (including his show at the Whitney Van Winkle Museum of American Art), we read how they are celebrating his “comeback”. Comebacks apparently sell well, better than a belated homage to an artist whose work has been ignored for forty years. Now, with whatever slogan it might be generated, Ira Cohen is not to be begrudged commercial success. Hopefully, it will give him enough financial wherewithal to devote the rest of his days to unencumbered dreaming.

The Resurrection of Iggy & The Stooges

Commercial interests will also undoubtedly have played a role in the comeback of Iggy & The Stooges. But it does not matter, because the return of this legendary band has primarily succeeded for reasons that are not monetary. While most comebacks of sixty-ish rock musicians are embarrassing spectacles, with sentimental value at best, the risen-again Stooges performances have remarkable strength and energy. This, of course, is mostly thanks to the individual qualities of guitarist Ron Asheton, his brother Scott on drums, bassist Mike Watt (replacing Dave Alexander, who died in 1975) and singer-performer Iggy Pop. Musically speaking, a preferable combination for a rock band is hardly conceivable, as was recently demonstrated at the Lowlands festival, where the Stooges left the younger musicians in the shade.

Iggy Pop and & The Stooges – “the name says it all” – are about conscious deconstruction of rock performance and rock music. “I took a ride with the pretty music. I went down, baby, you can tell. I took a ride with the pretty music, and now I’m putting it to you straight from hell,” sings Iggy Pop in the Stooges’ classic, “Loose”.(5) It does not matter that Ron Asheton has developed a considerable beer belly or that the skin sags on Iggy Pop’s cheekbones. From a visual perspective, such signs of decay as these are factors that support the Stooges’ comeback. In a rejected studio recording of “Loose”, we hear how Iggy Pop sang alternative lyrics: “Well, I’m flying on a red-hot wiener. Yeah, I’m riding on a big hotdog. It’s a thing that’s slipping easy. It’s a thing that’s big and long.” Elvis may have been the first white artist to have openly introduced references to sex in his music and his stage performances. But Iggy has the honour of having expanded such references, levelling the barriers between performer and audience to such a degree that the distinction between sexy performance and sexual act has disappeared. Iggy Pop is synonymous with raw, sexually laden, destructive energy, on stage and off. Elvis the Pelvis pales in comparison. When Iggy, now nearly sixty, his body battle-scarred, his torso bare and his pants hanging down to his notorious penis, sings, “I wanna be your dog”, it opens up a dimension in his performance that was not there in his younger years.(6) The strength of the Iggy & The Stooges comeback consequently comes not only from the mix of vital music and deconstructive rock performance that is characteristic of the Stooges, but also from the combination of sexual energy and physical decay. Lazarus is back and looking for sex.

A World in Dreams

In 1950, when Jan Wolkers carved his Lazarus eaten away by maggots from the marl of the Cauberg, in Valkenburg, he brought down the wrath of the city council.(7) The artist may have been allowed to defend himself by arguing that Lazarus only rose from the dead after four days, but that time in the grave was not supposed to have left any visible signs on his body. Wolkers’ sense of realism was deemed “in bad taste”. The objections generated by the sculpture were not entirely incomprehensible, for Jan Wolkers’ resurrection had literally exposed the worms in Christian resurrection mythology. Wolkers’ refusal to camouflage the physical reality of death cut right into a function of the myth, one clearly evident even in the Isenheimer altarpiece by Matthias Grunewald, so famous for its realism.(8) On that altarpiece, the martyred and crucified body of Christ is depicted in horribly realistic fashion, but as soon as the panels are opened and the painted resurrection of Jesus is made visible, all mutilation and signs of death ” with the exception of the stigmata” have vanished as if by magic. Christian resurrection myths do not support the physical reality of death. They repress them. Resurrections complete with decay and decomposing flesh have had to find a different place in our culture, through voodoo and folklore.

Lazarus the zombie. Lazarus de vampire. It seems an impossible combination. Where Christian resurrection myths sublimate our feelings about dead bodies, zombies and vampires are in fact projections of those feelings. Christians use bread and wine as substitutes for the body and blood of Jesus. Zombies and vampires, in contrast, are only satisfied with real flesh and blood – ours. Sublimation and projection are, however, two sides of the same coin. Only when they are seen side by side do we have a picture of the diverse and contradictory desires concealed in our fantasies of rising from the dead: “I am the First and the Last. I am the Living One; I was dead, and behold I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys to death and Hades.”(9) “The long-dead eyes devoid of all humanity, meet theirs. Long immersion in a damp and sullen grave has rotted and putrefied not only flesh, sinew, skin, membrane. It has fouled the very spirit that still lingers within the confines of the stinking skull, leaving only malevolence and blind, bestial blood-lust!!”(10)

Assuming material form, eternal life, cannibalism, necrophilia – whatever flights our fantasies of death and “undeath” might take, all the traits that we attribute to them evolve from a need to find a compromise in which we can both satisfy and repress our desires, be it in religious imaginings or comic strips, literature or folklore, high culture or low culture. Resurrection fantasies, including comebacks, are repeatedly fuelled by a mixture of universal desires for immortality and death, and by culturally determined responses to corpses, to the dead body. But what are we supposed to do with that knowledge? Doesn’t it leave us empty-handed? Perhaps it does. But personally, I’d rather pay my respects to the ashes of Freud in the Golders Green Crematorium in London than put my faith in the abandoned tombs of Lazarus, Jesus, zombies, or vampires. This does not mean that I fail to see the attraction of the mythical days of the resurrection, in which “the sun became black as sackcloth of hair”,(11) or “the lurid rays of the dying sun give the ancient buildings a bloody hue”,(12) even if it is only because I prefer the world of dreams to that of reality” at least in art.

Notes

1. From “Run Like A Villain”, by Iggy Pop, on their 1982 Zombie Birdhouse album

2. Things and ideas can also have their comebacks, but to my mind, these are cases of personification and bear no further relevance to this article.

3. “Long Gone” was recorded on Syd Barrett’s 1970 solo album, The Madcap Laughs.

4.”Etants Donnes” is the title of the work with which Duchamp meticulously staged his posthumous comeback at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Syd Barrett’s “Astronomy Dominie” was released on Pink Floyd’s first album, The Piper At The Gates of Dawn, in 1967.

5. “Loose” is from the second Stooges album, Funhouse, 1970.

6. “I Wanna Be Your Dog” is another Stooges classic and was included on their first album, The Stooges, released in 1969.

7. This autobiographical tale was described and later filmed in Turkish Fruit (1969 and 1973, respectively).

8. Grunewald painted the altarpiece between 1510 and 1515 for the cloisters of the Antonite Order, in Isenheim, near Colmar, Germany.

9. From the Bible, The Revelation to John

10. From the comic strip, “Rise of the Undead” from Vampirella magazine, #51, 1976, text by Flaxman Lowe

11. From the Bible, The Revelation to John

12. From the comic strip, “Rise of the Undead”, from Vampirella magazine, #51, 1976, text by Flaxman Lowe

This article was first published in Dutch art magazine Metropolis M #6, December 2006/January 2007, republished with permission of the author, all rights reserved by Ben Schot.

Ben Schot is an artist, curator, author and publisher who lives in Rotterdam, Holland. He contributes to artistic journals and radical endeavors in print and online. He is the mind behind Sea Urchin Editions, a small independent Dutch press that reproduces classic surrealist texts .